15 Years Ago: Three Volcano All-Road Brevet

It’s hard to believe that 15 years have passed since I got my first real taste of the performance of all-road bikes. On a Saturday in August 2005, the second Three Volcano 300 km Brevet was organized by Robin and Amy Piper of the Seattle International Randonneurs. The previous year, I had ridden the event on my road bike with 28 mm tires—which were considered wide then!—but they proved ill-suited for the loose gravel of Babyshoe Pass. In 2005, I decided to ride a 1952 Rene Herse with wider 650B tires. The result was a FKT (fastest known time) that stands to this day, and a new appreciation of the amazing performance of the best mid-century all-road bikes.

Most of all, it was a perfect day: just me, a great bike, and a wonderful course. We published the story of that ride in Bicycle Quarterly 13. That edition is long out of print, so we’ve decided to reprint the article here. Enjoy!

A 300 km Brevet on a 1952 René Herse

“Aren’t those fat tires hard to push?” asks the rider next to me as we roll along the meadows in the morning twilight, shortly after the start of the Seattle International Randonneurs Three Volcano 300 km Brevet. “Not at all,” I reply, realizing that the effort and speed are roughly the same as on my other bikes equipped with 28 mm tires. I wonder what the other rider would say if I told him that the 650B x 36 mm tires of this 1952 René Herse are pumped up to only 3.8 bar (55 psi). [Note: Today, 3.8 bar/55 psi is way more than we’d put in our 36 mm-wide tires, but this was in 2005…]

The road is a bit higher than the surrounding meadows, which are shrouded in fog. Our attention focuses on two large animals next to the road – elk. Fortunately, they move away and disappear among the shadowy outlines of cows in the pasture. Then I see a small, long-tailed animal run across the road. “Fox?” I ask David Huelsbeck, who is riding ahead of me, leading the paceline. He nods his head. The magic of early morning rides are the sights and sounds you don’t experience during the day. After 45 minutes of pleasant spinning, we turn off the highway, and the first climb breaks up our group. On a course that is either up or down, there is little hope of staying with other riders, as each climbs at their own speed. In any case, many of us are trying to rise to the challenge, and see how fast we can go.

I reach behind the seat tube, move the shift lever, and the chain smoothly drops into the middle chainring. A tug at the downtube lever moves the chain to a larger freewheel cog, then another and another, until I have found the perfect gear for this first hill. As the grade steepens and slackens, I marvel at how easy it is to shift the old Cyclo rear derailleur. Having done Paris-Brest-Paris on a similarly equipped tandem, the ‘reverse action’ of the shift lever (toward the rider gets a smaller cog, away a bigger one) only requires a few miles to become second nature again.

The road becomes a false flat. I shift back into the 48 tooth big ring, and enjoy the ride through the trees. An small lake appears on my left. The dark water contrasts with the greenish-grey tree trunks touched by the first rays of the sun. Soon I reach the first control, where one of the organizers, Amy Pieper, signs my card and wishes me luck.

The road continues along the Cispus River. Gaps in the trees allow me to catch a glimpse of the milky water running in numerous channels over large, round gravel. The Cispus River springs from the glaciers on the slopes of Mount Adams, one of the large volcanoes in the Cascades.

A short descent brings me back to the valley floor, where fog still hangs over the meadows. The hamlet of Cispus Center appears. The sun is starting to pierce this blanket of white, with beautiful light outlining the few houses and barns along the road. I greet a couple of runners, then enter the forest again and start climbing.

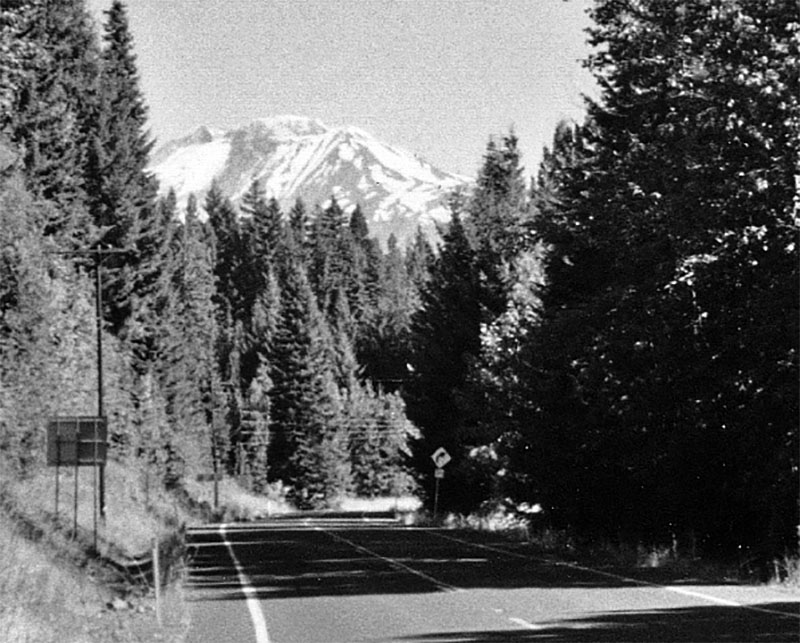

Babyshoe Pass is not marked on most maps of Washington State, and very few even show this road. As I look up, I see the massive peak of Mount Adams looming above the trees. The road continues to climb the flanks of this huge volcano. For the past two hours, I have not encountered any traffic at all. I am grateful that this road remains off the beaten path. After winding up the sides of the Cispus River valley, the road turns to gravel. My bike remains at ease, climbing confidently under my pedal strokes. The wide tires deal with the loose rocks without problems. I had planned to let out some air for the gravel section, but for now there is no need to do so.

The cool, foggy lushness of the valleys below is but a distant memory now. As I climb above 1,000 m (3,300 ft) in elevation, the trees are less dense, and even at 8 a.m., it is getting warm on this summer day. I realize that apart from my nylon shorts and my helmet, the scene could date from 1952, when this bike was new. It is likely that neither the landscape nor the road have changed since then. But it is not out of nostalgia that I have chosen the old René Herse for today’s ride. Last year, I rode my Rivendell with 700C x 28 mm tires on this brevet. With 18 km of gravel, and poorly maintained roads elsewhere, this year I knew I would be much happier on wider tires. The twisty descents require good brakes, and, with so much climbing, I wanted a bike that I enjoy riding.

The road flattens out a bit, and I use the lever behind the seat tube to engage the 48-tooth chainring. Where I bogged down last year on narrow tires, the bike now storms up the mountain with only an occasional shift on the rear to take care of variations in the slope.

The road steepens and turns into switchbacks, so I drop the chain back to the middle chainring. Shifting the lever-operated front derailleur is incredibly smooth, as it simply derails the chain, which then continues the shift on its own. The spring-less derailleur floats and always stays centered on the chain.

The top of the ridge comes into view, indicating that Babyshoe Pass is near. I stop before reaching the crest. Counting to five as I depress the valve, I let out some air to reduce the tire pressure to about 2.5 bar (37 psi). (I have practiced this a few days ago, so I do not have to bother with a pressure gauge on this ride.) The washboard is getting worse, and on the downhill, the extra shock absorption is worth the time lost adjusting the pressure. As I crest the pass, I look on my route sheet, then at my watch. It is 8:37 a.m, and I am exactly on schedule.

Descents on gravel roads usually are fun, but with the sun behind me, it is hard to see the washboard. Suddenly the bike hits the undulations and begins to shake violently. Deeper gravel on some switchbacks causes the bike to float. The messages coming up from the tires are very vague, and I wonder whether I will make it around. The secret here is to keep the bike pointing roughly in the desired direction and to let it float without overcorrecting. After a few kilometers, it is with relief that I find myself on pavement again. At the next intersection, I lean the bike against a signpost and inflate the tires. 45 strokes per tire… I notice that my bell has gone missing on the washboard. Even if I turned around, my chances of finding it would be slim. Fortunately, of all the pieces that could fall off this bike, the bell is relatively easy to replace. Next time, I will put some beeswax on the threads.

I look forward to what I remember as a long downhill to Trout Lake. Unexpectedly, the road rises and falls for a few kilometers as it winds its way along the flanks of Mount Adams. The rises are not entirely welcome, because I have exhausted myself a bit on the pass, and would prefer some easy spinning to recover. Soon the real downhill begins, and I am spinning comfortably in my largest gear (48 x 14, 6.98 m/88 in). The road here is very smooth. When I take my hands off the handlebars, the bike veers to the left. To ride no-hands, I have to lean my body far to the right. The bike usually does not do this, but I have replaced the wheels for this ride. Obviously, something is different – these bikes with little geometric trail are very sensitive to small misalignments.

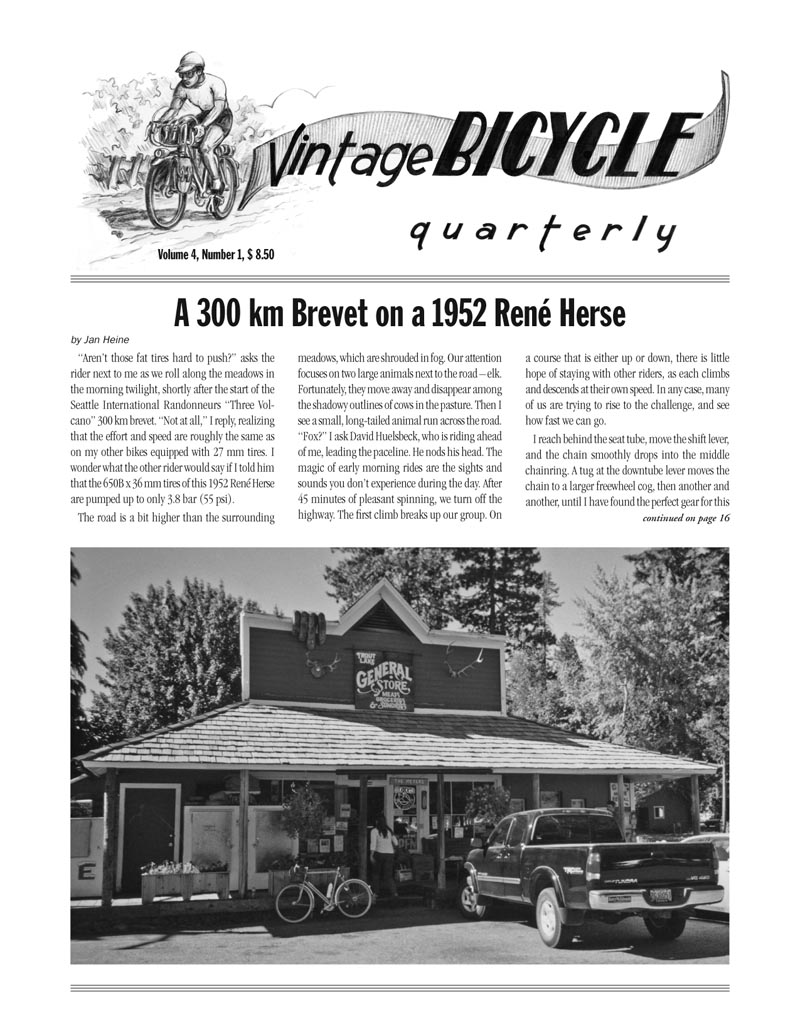

Before long, I reach Trout Lake, a small town on the White Salmon River. Looking back, Mt. Adams still looms large. This control is ‘open,’ meaning riders can have their card signed at any business. I peek into ‘KJ’s Café,’ but it’s full of people sitting at empty tables, waiting for their breakfast. I realize that my needs are more easily met at the General Store, a cute building full of frontier charm. Unable to find apple juice, I buy Gatorade, fill my bottles 2/3 with water, and top them off with the electrolyte replacement drink. I remove the front wheel and reinstall it the other way around, hoping to cure the alignment problem. After 3 minutes, I am back on the road. Turning the front wheel had no effect, but fortunately, the problem only appears when I ride no-hands.

The route parallels the White Salmon River a little longer before going up Trout Creek. Instead of following the creek closely on a moderate grade, the road traverses very ‘humocky’ terrain with lots of ups and downs. The grades are not very steep, but the incessant undulations result in a lot of cumulative elevation gain. Always within the trees, it is hard work without offering the satisfaction of having climbed a mountain pass. After a while, the road turns into a single lane. Every mile or so, turnouts allow oncoming cars to pass one another. Even thought I have encountered only a car or two in the last hour, the narrow road requires vigilance when descending around the many blind turns. Every half-hour, I eat half an energy bar to fuel my body.

After riding in this featureless landscape for 30 km (19 miles), the route joins the Lewis River. Towering basalt cliffs and the stream gleaming in the sunlight provide a welcome change of scenery. Once again, the road follows the river only approximately, which means a series of climbs and descents. A few short gravel stretches add excitement to the descents, especially since the tires float a lot more at full pressure than they did on the descent from Babyshoe Pass.

I am working harder than I should. It is tempting to carry as much speed as possible on these smaller climbs, rather than bog down and climb each one individually. As a result, I am a little tired when I reach the next control, Northwoods, at lunchtime. A volunteer is just setting up the control, so I have my card signed at the store, buy some more Gatorade and two cans of Coca-Cola (no re-closable bottles available here), and head out after about 5 minutes.

I cross the Lewis River on a large bridge. On the gravel banks below, swimmers and sunbathers enjoy the sunny day. Before long, I reach the final, and hardest, climb of the ride: Elk Pass. It is hot now, approaching 32°C (90°F). The first switchbacks pass without problems, as I am climbing smoothly in the middle ring. Soon I realize that I cannot maintain this tempo, and switch to the little ring. Even that becomes hard to turn, so I stop to drink my second can of Coca-Cola.

A kilometer further, I realize that I am suffering from the dreaded bonk – a visit from the ‘Man with the Hammer,’ as the French call it, makes it difficult to continue. My vision blurs. Knowing that the climb is long, I decide to stop and rest for a short while, rather than suffer for the entire climb. I lay down the bike on the grassy shoulder, and stretch out next to it. Sweat is running down my entire body, dripping not just from my brow, but also my back, my arms and my legs. Clearly, I have overdone it a bit on the hills before the last control.

After a few minutes, I begin to feel better. I mount the Herse again, and continue the climb. Soon, the grade eases, and the bike surges ahead, beckoning me to shift into the middle ring. I am regaining my strength, and I begin to enjoy the climb again. When the trees open, I see the huge, hulking mass of Mount St. Helens across the valley. When Mount St. Helens lost its top in the eruption in 1980, the glaciers on its flanks lost their accumulation zone, where snow turns into ice that feeds the glaciers. Starved of ice, the glaciers disappeared. So instead of the cheery bluish white and grey of the other volcanoes, Mount St. Helens’ color is ashen grey.

The mountain soon fades from view as trees close in again. I reach a ‘secret’ control, where I see Amy Pieper again. After the solitude of the road, it is nice to see a familiar face. To my surprise, she inquires whether I have crashed. Only now do I notice that my jersey is covered with leaves from my rest next to the road. Apparently, Amy does not believe my explanation… I sit down on a folding chair, drink some more cold Coca-Cola, refill my bottles, and soon set off. Amy tells me that it is another 2 miles (3.2 km) of uphill. I pace myself for this distance, only to find that there are a few more kilometers of false flats at the top. Finally, I reach Elk Summit and plunge into the descent.

The next 16 kilometers are downhill, with very little pedaling required. Once in a while, I see Mount Rainier above the trees, but mostly, I have to concentrate on the narrow, twisty road with numerous washouts. The Herse shines on this descent, exhibiting exactly the right amount of stability – enough to run straight and stable when I need it, but not so much that I cannot make last-second changes in line to avoid a crack or hole in the asphalt. The cantilever brakes scrub off speed effortlessly where required, but the confident handling means that I rarely brake at all.

Before long, I reach the Cowlitz River valley again, exactly at the point where we entered the mountains this morning. All that remains are 26 km (16.3 miles) along the main road with a slight tailwind.

The afternoon sun bathes the bucolic valley in soft light. No more hills – no need to hold back any more! The short 165 mm cranks mean that pushing big gears is useless, but they are easy to spin even after having ridden for 11 hours. Without a bike computer, I wonder about my speed. I time myself between mile markers as I zoom along the valley. Every mile passes after 2:45 minutes. I calculate my speed: 21.8 mph (34.9 km/h).

As the mile markers pass with pleasant regularity, I reflect on the bike. It really works for me. Whether it is the low Q factor or the frame having just the right amount of flex, the Herse always beckons me to go faster. Even this far into the ride, it is easy to maintain my cadence and speed. Only the short reach to the handlebars compared to my other bikes causes my back to ache slightly after 11 hours on the bike. A longer stem would be useful, but even so, the Herse is an extremely capable and pleasant bike.

I have enjoyed this wonderful ride, but I am relieved as I enter the town of Packwood. I know I cannot maintain this pace much longer. At 4:49 p.m., I arrive in front of the hotel that serves as the final control, 11:49 hours after I started – a new course record. The bike is dusty, but apart from the lost bell, it is none the worse for wear.

Further Reading: