80 Years of Rene Herse Cycles

When Compass Cycles became Rene Herse Cycles earlier this year, many cyclists wondered: Who was René Herse, and why is his work relevant today? Here is the story of how René Herse and his bikes have inspired modern all-road bikes:

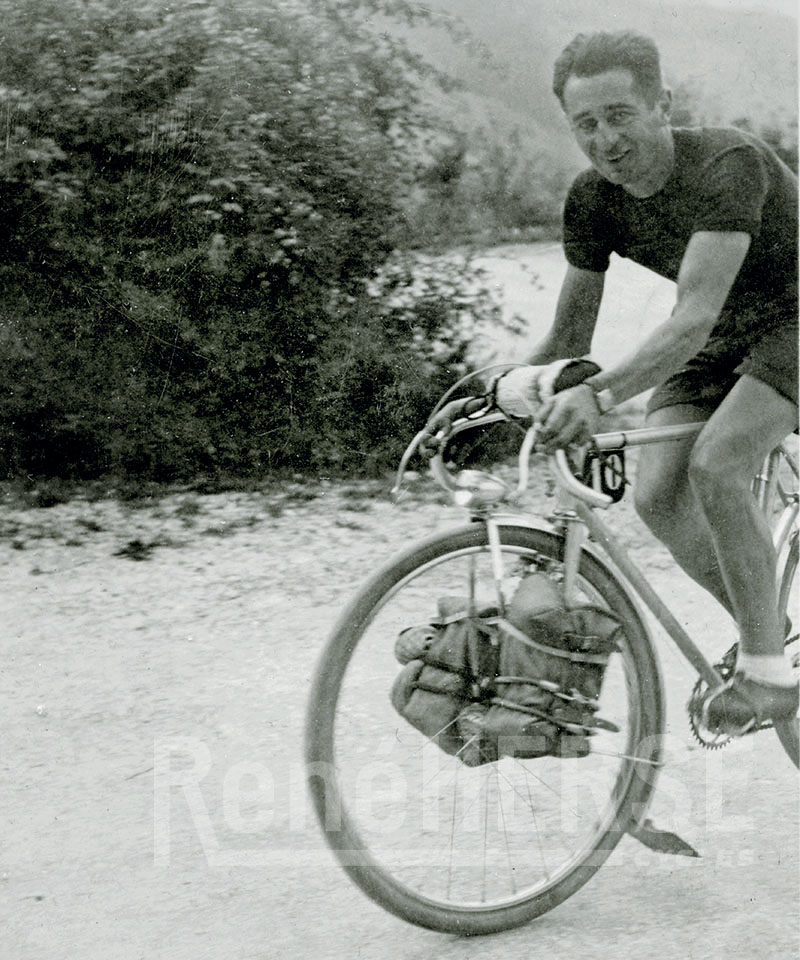

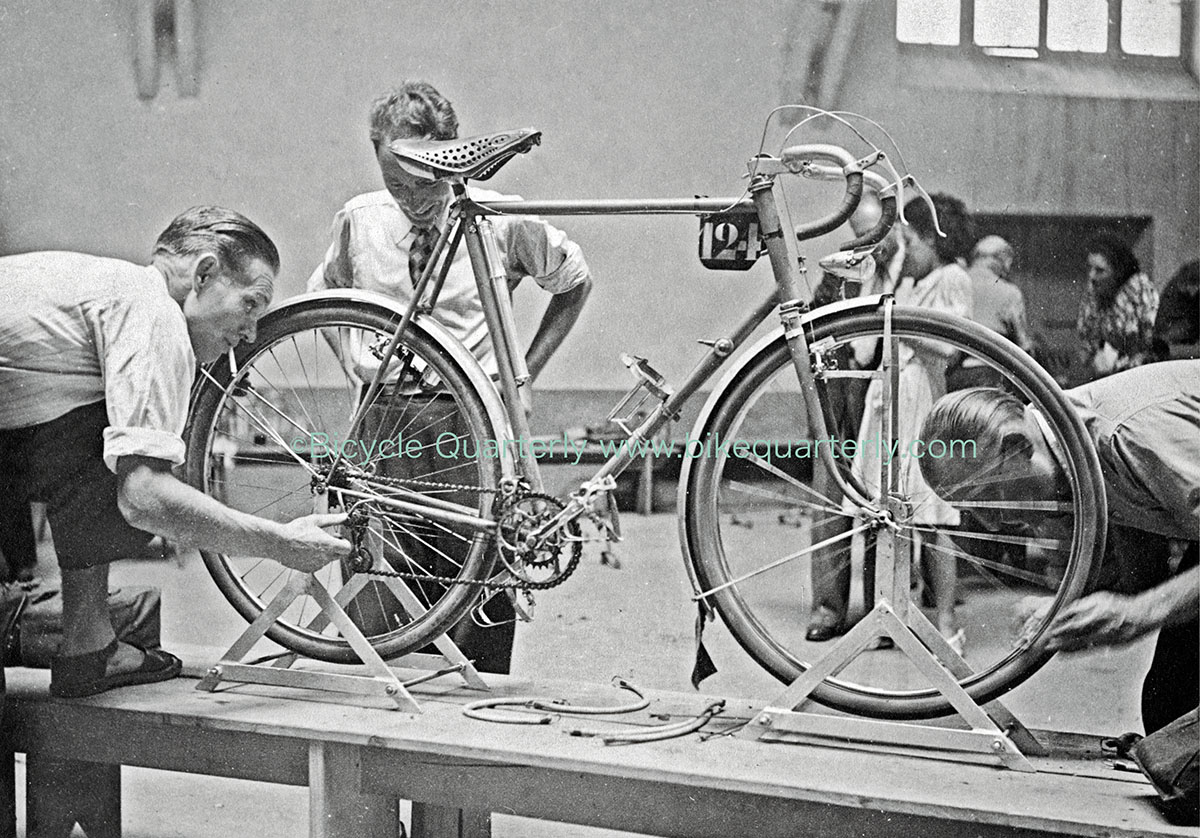

Eighty years ago, René Herse entered the cycling world with a splash when he entered the lightest bike in the 1938 Concours de Machines technical trials (above). Fully equipped with wide tires, fenders, rack, lights and even a pump, this amazing machine weighed just 7.94 kg (17.50 lb). Not only was Herse’s bike incredibly light, it also was strong: The Concours included 680 km (425 miles) of hard riding on rough mountain roads, with penalties for any parts of the bike that broke or stopped working.

Gravel roads in the mountains, spirited riding, carrying the supplies for your adventures: This sounds exactly like modern all-road riding and bike-packing! René Herse loved this style of riding, and he designed his bikes and components specifically for it.

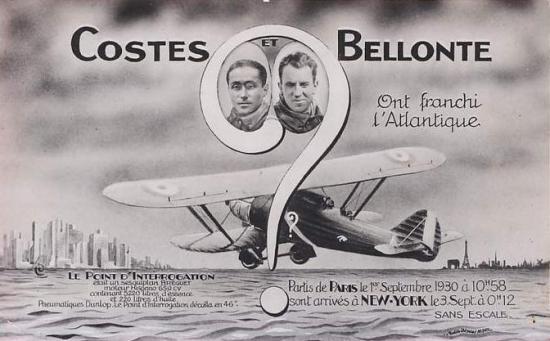

Who was René Herse? During the previous decade, he had worked at Breguet, France’s leading aircraft builder. He made parts for prototype aircraft, including the famous ‘Question Mark,’ the first plane to fly from Paris to New York, in 1930.

We all know about Charles Lindbergh’s famous flight in the other direction, just three years earlier. Lindbergh was aided by powerful tailwinds. Going the other way was much, much harder.

The ‘Question Mark’ had three times the horsepower of Lindbergh’s ‘Spirit of St. Louis,’ yet it took seven hours longer to make the trip. The two pilots landed in New York after more than 37 hours of non-stop flight (above). It was a monumental achievement, and all his life, René Herse treasured the medal he received for his part in this success.

Applying the knowledge gained from working on planes, Herse designed and made lighter, stronger bicycle components. The Concours de Machines was the best place to perfect them.

During his premiere in 1938, René Herse’s bottom bracket – one of the few unmodified parts of his bike – developed play, costing him first place. He wasted no time to develop a better bottom bracket, with pressed-in bearings that lasted for decades. At the 1947 Concours, his bike (above) won, with zero technical problems after hundreds of high-speed miles on gravel roads in the French Alps.

Based on the experience of the Concours de Machines, Herse developed bikes that stood heads and shoulders among the machines that had come before. They were superlight, extremely reliable, and beautiful. He equipped them with his own components and with supple, handmade tires that he sourced from specialist makers.

Herse’s specialty were randonneur bikes, but the quality of his frames wasn’t lost on the biggest names in racing. More than a few came to the workshop in Levallois-Perret, just outside of Paris, to order frames. Lyli, René Herse’s daughter, told me how world champion Briek Schotte waited for the final assembly of his bike the day before a big race, eating a sandwich “as long as my arm.”

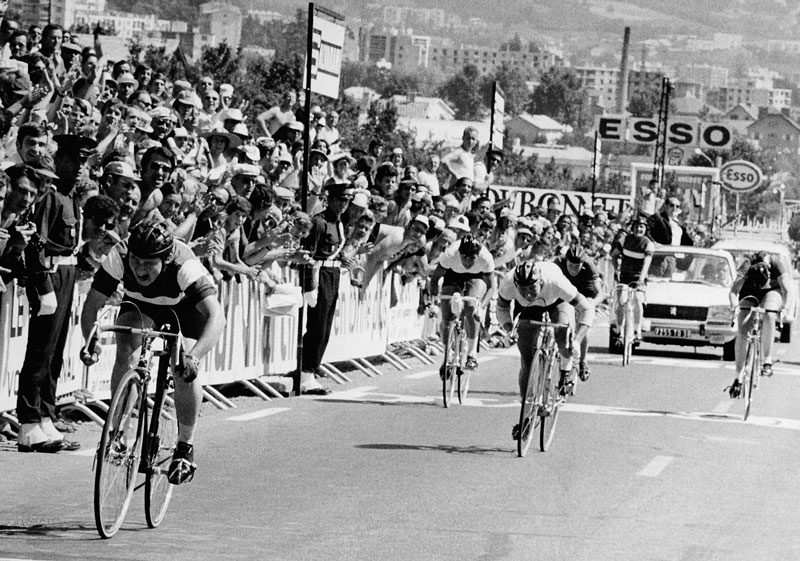

Herse supported his own team of randonneurs, who dominated the cyclotouring competitions of the 1950s and 1960s. The photo above shows Robert Demilly (front) and Maurice Macaudière on the way to setting a new record in the 1200 km Paris-Brest-Paris in 1966. Their time of 44:21 hours for this incredible distance (which translates to 750 miles) remains competitive even today.

Lyli Herse was an incredibly strong rider herself: She won no fewer than 8 French championships. When she wasn’t racing, she worked in her father’s shop, building wheels and managing the component supply.

After Lyli retired from racing, a few young women asked her for training advice. Lyli formed a team that continued her successes – including two world championship titles by Geneviève Gambillon (above).

Herse also continued to build bikes for adventures that spanned entire continents: Paris to Istanbul, a trip across Northern Africa, the West Coast of the U.S. by tandem…

After her father’s death, Lyli took over Rene Herse Cycles. She was married to Jean Desbois, who had been Herse’s best framebuilder in the 1940s and 1950s, and again in the 1970s. Together, they continued to build amazing bikes until Jean’s health problems forced them to close the shop. When the word spread that this might be the last chance to get a Rene Herse, Lyli received so many orders that Jean had to work out of their house for two years to complete the bikes.

I met Lyli through my research into the bikes her father had built. When we started to explore the gravel roads of the Cascade Mountains in the early 2000s, we realized that Herse’s amazing machines provided a perfect blueprint for the bikes we needed. So I contacted Lyli Herse…

At first, Lyli wasn’t sure what to make of the young American who wanted to talk about her father, but when Jaye Haworth and I rode a 1946 Rene Herse tandem in the 2003 Paris-Brest-Paris, she warmed up and agreed to meet me.

Over the next 15 years, I visited Lyli and Jean many times. I learned everything I could about René Herse and what made his bikes so special. Jean explained how to make the iconic stems and how to bend the tubes for the racks and for the amazing Chanteloup tandem frames. Others who had worked at the shop shared additional information, and interviews with suppliers shed more light onto the production processes.

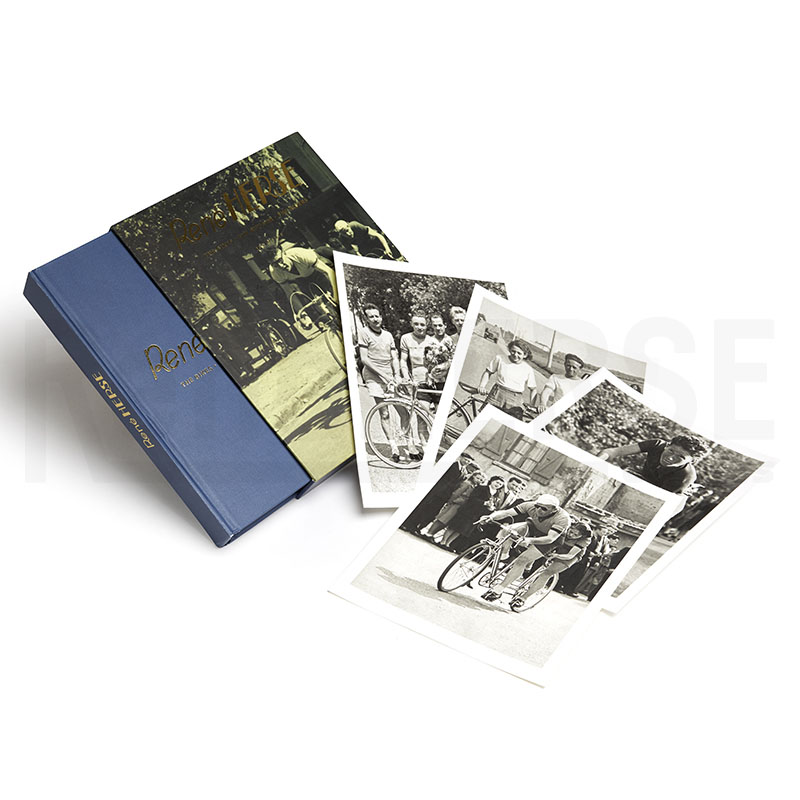

Rummaging through Lyli’s garage in search of parts and tools, we came upon two suitcases of photos: the Herse family archives, compiled by her mother. Seeing the bikes, the workshop and the riders in these amazing images was the last piece in the puzzle of researching Rene Herse Cycles. Our acclaimed book René Herse • The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders was the result.

During one of my visits, Lyli told me that she worried about the future of the Rene Herse name. She had no children, and she was afraid that after her passing, the name might be used in ways that her father might not have approved of. She now wished that she had sold the brand and passed it on to a successor. As she looked at me intently, I realized that she was asking me to continue Rene Herse Cycles.

I was not yet ready to take on that responsibility, so I brokered a deal between Lyli and my friend Mike Kone to take over the name, while I bought the remaining tools, documents and other physical assets of the company. Mike made a few Rene Herse bikes in Colorado, before the brand reverted to me.

That is how Rene Herse Cycles was reborn in the Cascade Mountains. Inspired by Herse’s famous originals, we’ve introduced cranks, brakes and other components that are ultralight and offer excellent performance. We’ve developed wide, supple high performance tires that allow us to traverse entire mountain ranges.

When the Concours de Machines was revived in France, we joined forces with J.P. Weigle to enter a bike in the spirit of the great constructeurs. Combining Peter’s mastery with Herse’s designs, the bike was the lightest to finish the difficult event, and one of the few that didn’t have any technical problems. Lyli was proud when we visited her after the event.

Sadly, Lyli died last year, on the day that would have been her father’s 110th birthday. We lost a dear friend, who surprised us during every visit – such as when she gave Natsuko and me a rose from her garden in 2016.

As Rene Herse Cycles is reborn in the Cascade Mountains, it’s our goal to keep the brand as relevant in the future as it has been for the last 80 years. Like Herse, we enjoy spirited rides far off the beaten path. Our riding experience has defined our philosophy: Only the very best is good enough. Performance is more important than fashion. And when our bikes are beautiful, we want to ride them more. These are the principles that guided René Herse. They continue to guide us today and into the future.

Further reading:

Photos are from the Rene Herse book, except: Natsuko Hirose (Photos 1, 12, 13, 20), Maindru (Photos 14, 16), Nicolas Joly (Photo 19), Duncan Smith (Photo 21).