Video: How a Bicycle Is Made

A reader sent a link to the video “How a Bicycle is Made,” filmed in the 1945 at the Raleigh factory in Britain. It’s definitely a period piece, but look beyond that, and the 17-minute movie has a lot of interesting content about how bikes were mass-produced. Some production methods have changed – TIG-welding has replaced stamped lugs – but many things remain the same. It’s amazing how everything is geared toward efficiency, especially when you compare it to making a hand-built frame and manufacturing top-tier components.

Click above to watch the movie. Here are a few things that I found interesting as I watched how Raleighs were made…

The movie starts with making the bottom bracket shell. A flat steel disc is pressed into the shape of a bottom bracket shell – it’s truly amazing how ductile steel can be! Raleigh’s tubing was made from flat steel, rolled into a tube and welded at the seam.

Today’s high-end lugs and bottom bracket shells are cast to ensure even wall thicknesses and a precise fit that’s required for silver-brazing. High-end tubes are drawn – meaning they are pushed through a mandrel to create the tube and then butted, so the ends are thicker for strength at the joints, while the center sections are thinner for light weight and just the right amount of flex.

You’ll be surprised how fast a frame can be made when all the tubes are cut to just the right length. It requires a lot of setup, but when you make hundreds of frames in the same size, every second saved in the assembly makes a difference.

With heavy-gauge tubing, overheating isn’t a big concern. So rather than use a torch, the joint is heated until it glows. It’s not explained in the movie, but there’s ring of brass inside the joint – placed there during the assembly on the jig. In the furnace, the brass melts and is drawn into the lug by capillary action. You can’t do this with thinwall tubing – the steel loses some of its strength when it’s heated this much.

Painting the frame takes just a few seconds – it’s just dipped in a big vat of paint. It’s impressive when you’ve seen old Raleighs – the paint is smooth and shiny. Of course, the paint has to be just the right consistency and temperature…

Despite all the labor-saving measures, even production frames had lining on the tubes – applied using these guides and a paint wheel, rather than the long brush and free-hand that on custom frames. (Making a guide like this for a curved seat tube would be quite a job!)

Raleigh made the components for their bikes in-house, too. The fenders start out as a roll of sheetmetal, which is formed into a spiral of fender shapes and then cut into individual fenders. That part isn’t too different from how Honjo in Japan makes our Rene Herse fenders (except we use aluminum instead of steel)…

… but spot-welding the stays onto the fenders is definitely a short-cut that saves labor and cost.

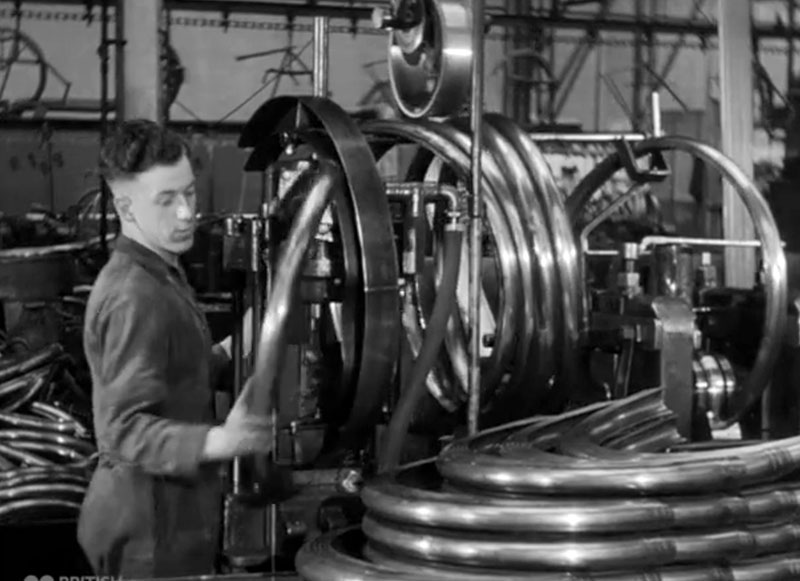

Stamping the chainring teeth is also something you find only on inexpensive parts… It’s fun to watch – and so much faster than CNC-machining each tooth in multiple steps.

Heat-treating steel has a relatively large window of acceptable temperatures. Aluminum has a much lower melting point, and you need better control of the temperatures.

The skill of the assemblers is remarkable. The spokes are threaded into the hub in one go…

… and tires are mounted on the rim in less than 50 seconds. Now you know why OEM rims traditionally are a bit undersized – it makes the tires go on easier. Recently, this has become a problem with tubeless tire setups, where the slightly loose tire fit can cause blow-offs.

It’s a fun movie, but the portrayal of gender roles is dated. Back then, men did jobs that required muscle, while women’s specialty was finesse – like drawing the lines on the tubes or threading the hubs. The three protagonists of the movie – the engineer, the visitor and his son, are all male.

Yet it’s encouraging to see the final scene: a group ride that includes both women and men. It shows that cyclists themselves were much less stuck in the traditional gender roles than the ad people who made the movie. As Jack Taylor’s wife Peggy explained in Bicycle Quarterly 28: Women were accepted as equals on club rides long before the rest of society caught up.

Enjoy the movie!