Oregon Outback Rene Herse: Method or Madness?

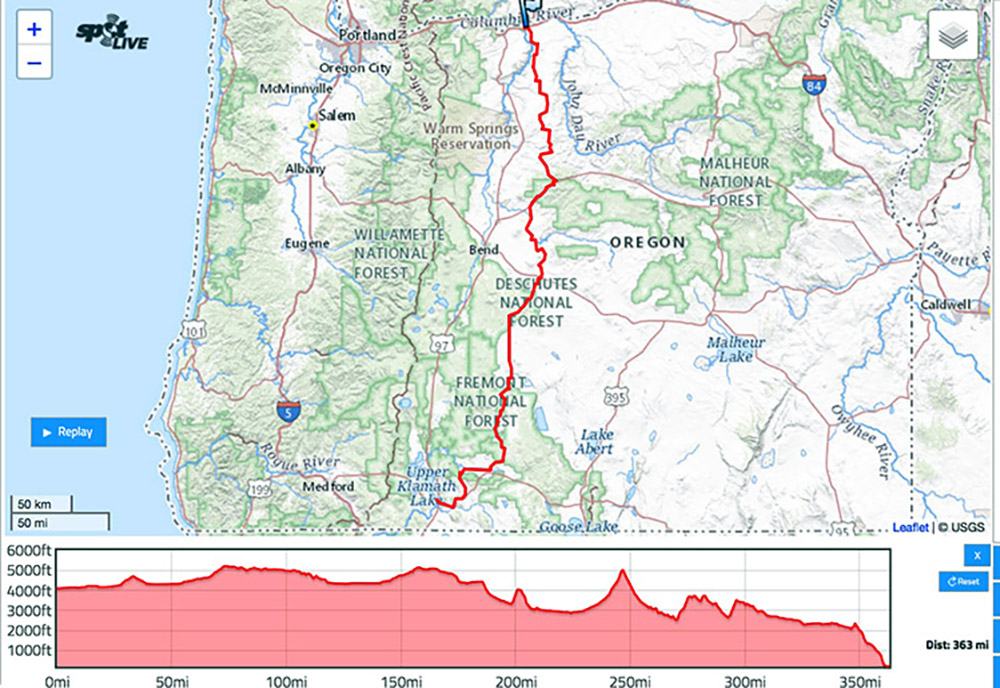

“26in?! Why not a big fat 700c tire?” asked the Velo-News editor when he heard about my FKT (Fastest Known Time) on the Oregon Outback, the 363-mile (585 km) bikepacking route that stretches all the way across Oregon, from the California border to the Columbia River. So much of my bike goes against bike industry trends… Why not a carbon frame? Aerobars? Disc brakes? Electronic shifting? It would be easy to dismiss my Rene Herse as a retro machine ridden by a lover of mid-century French bikes.

Except for the fact that the bike was 1:14 hours faster than the previous best. As much as I’d like to claim superior legs, all the other racers who have ridden the Oregon Outback in less than 30 hours are stronger and faster than I am. If it’s not the rider, then the bike at least has to contribute…

Ever since the inaugural Oregon Outback in 2014, my dream has been to build a bike that can traverse the rough trails and loose gravel roads of eastern Oregon at road bike speed. When you look at the rough surface of the OC&E Trail (below), which makes up the first 70 miles or 20% of the Outback course, you may think: “Impossible!”

The terrain of the Oregon Outback sure is rough! You are basically riding across cow pastures. In fact, there are more than 30 cattle gates that riders have to open and close… The photo shows Lael Wilcox (white jersey) and me (blue) during our first attempt at an FKT ride on the Oregon Outback earlier last year. Lael’s time of 27:58 hours makes her the fastest woman ever on this course. (My ride that spring was marred by a number of mishaps. That’s why I went back in September to have another go at the Outback.)

Dreaming of a road bike for the Outback may seem like pure madness. And yet – if wide tires are as good as we think, why wouldn’t they glide over this terrain with (almost) road bike speed?

To put my time of 26:13 hours into perspective, the fastest randonneurs ride a 600 km brevet in 23-24 hours if conditions are good – on pavement, working as a group. Essentially, I was going at 90% of my pavement speeds – solo and across some very rough terrain. And that is how it really was: Looking at the GPS track, when the road surface changed from paved to deep gravel, my speed dropped by 10% – surprisingly little. I didn’t even shift gears, since the rough surface required a slightly lower cadence. The secret to that speed is a special bike.

I don’t intend to say that other bikes don’t work as well for their intended purposes. There are many wonderful bikes out there. In fact, I did much of my training for the Oregon Outback on an OPEN MIN.D. carbon racer that Andy and Gerard from OPEN allowed me to keep long after the Bicycle Quarterly test was complete. I love that bike, and on a fast-paced, paved ride in the hills, it’s just about perfect…

Riding non-stop for a day and a night across rough terrain is a pretty specialized application, and there’s probably not a huge market for a bike that’s optimized for that. Today’s gravel racers can choose road bikes with low, stretched-out positions that facilitate generating power and help with aerodynamics – but road bikes are limited to relatively narrow tires. For smooth gravel courses, that’s often the best choice. That’s why you see riders win races like SBT GRVL on 35 mm tires. Not because narrow tires are faster, but because road bikes are faster, and they don’t fit wider tires.

For rougher courses, there are gravel bikes or drop-bar mountain bikes. Most of these are designed for more upright riding positions. They usually run wider handlebars – necessary for tight turns on singletrack – and wider cranks to clear the wide tires. Lael was riding the bike she uses for the Tour Divide. For a ride that takes two weeks, a more upright position is probably essential, but I knew that for just over 24 hours, I’d be just as comfortable, yet faster, with a road-bike position.

What if you don’t have to choose between the efficiency of a road bike and the rough-terrain speed of ultra-wide tires? That was the idea behind my bike, and everything else follows from there.

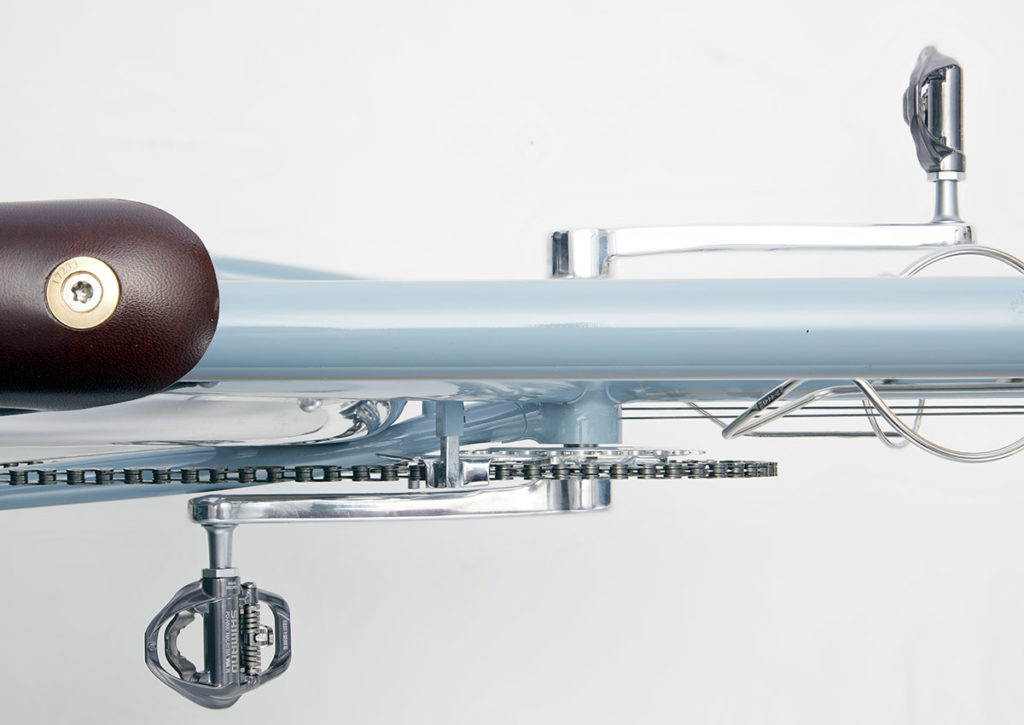

You’ve already noticed the road-bike position, with the bars lower than the saddle and pushed forward for a stretched-out (but not extreme) riding position. Why 26″ wheels? Much lighter and easier to package into a road frame, without needing an overly long rear triangle that adds weight and flex where you don’t want it. Plus more nimble handling, since the rotational inertia is the same as a 700C x 32 mm wheel. Why a steel frame? A one-off is almost impossible to make from carbon. And tuning the frame stiffness to my pedal stroke is much easier with steel, which is available in many diameters and wall thicknesses.

One essential element of a road bike is the narrow Q factor (the distance between the cranks). A study at the University of Birmingham confirmed what generations of road cyclists have known: Most riders pedal more efficiently with a narrow Q factor. The Oregon Outback bike has a Q factor of 146 mm – the same as good road cranks, and quite a bit narrower than most ‘gravel’ cranks.

There’s just enough room between the wide tires and the crankarms for beefy and stiff chainstays. I had to remove a little material from the inner ends of the crankarms, but that’s easy to do with aluminum cranks, and there’s no risk, since cranks never break there. (It’s a trick I learned from mid-century Rene Herse all-road bikes…)

What about the cantilever brakes? The best disc brakes work great, but they require stiff fork blades, since the brake force is transmitted via the fork legs. Canti brakes allow me to run slender Kaisei ‘Toei Special’ fork blades, which provide a significant amount of suspension. On the rough terrain of the Oregon Outback, that brought comfort and speed, since it reduces the vibrations that cause suspension losses. The alternative would be to run a suspension fork, as Lael did, but that adds a lot of weight. Of course, not all canti brakes are created equal: I’ve cured severe brake judder on my cyclocross bike by switching to our forged Rene Herse cantis with their precision-machined bushings.

The Rene Herse cantis are also much lighter than disc brakes, and they brake just as well, unless it’s very wet and cold. On gravel, I prefer the direct connection from tire to brake lever, which lets me feel when the front wheel is about to lock up. Disc brakes have their place, but good rim brakes can work really well on gravel.

Speaking of weight, the entire bike – with bottle cages, pedals, lights, rack and even the pump – weighs 10.3 kg (22.7 lb). That’s lighter than the bikes of the other racers who’ve ridden the Oregon Outback. How can a steel bike be so light? Frame and fork make up only 20% of the bike’s weight. The savings are in the other 80%, mostly in places that few riders think about. Example: There’s no heavy light mount (which also tends to rattle loose), because the light attaches directly to the rack. That’s the beauty of a custom bike built for riding ultra-long distances: Everything is part of the original design. There are no add-ons or afterthoughts.

Another important element is reducing the need to stop. Having an integrated light switch means that I never have to fiddle with my lights. After the sun sets, I simply turn the stem cap, and the lights are on. And off again in the morning. Climbing Antelope Hill under the full moon, I turned off the lights to save a little resistance.

I considered a battery-powered system to eliminate that resistance altogether. But there’s simply no battery lighting that integrates as nicely into the bike. And there are no battery-powered headlights that illuminate the road as well as the shaped beam of my Edelux II headlight. I calculated that I lost about 10 minutes powering the lights during the 12-hour night in late September, but I gained more by being able to see the road so well that I could let the bike roll at full speed on the twisty gravel descents of the Ochoco Mountains. And not having to worry about battery charge meant I could focus on riding.

Many gravel racers mount a forest of lights, GPS and phone holders on top of their stems and handlebars. I prefer to keep the top of the bars clean, so I can get into the aero tuck on downhills, with my hands next to the stem and my chin right above. Why pedal when it’s faster to coast?

Speaking of aerodynamics, that’s the reason for the truncated fenders. Our wind tunnel tests show that they provide as much of an advantage as aero wheels by shielding the tops of the tires – which move twice as fast as the bike – from the airstream. Don’t believe it? Check out a Moto GP bike – it has similar fenders for the same reason.

The same applies to the handlebar bag. Our testing indicates that it acts as a fairing. Even more importantly, the front bag keeps my food and clothes easily accessible without stopping. Add the super-comfortable handlebars, and I can spend more time on the bike than most riders, without any aches and pains. At the finish, after riding 26 hours with just three stops and less than 30 minutes off the bike, my legs were tired, but my arms, shoulders and wrists didn’t hurt.

It’s easy to get distracted by the ‘crazy’ Nivex derailleur. I’m the first to admit that a modern electronic shifting setup would have worked just as well. That said, the Nivex is superlight – lighter than a Dura-Ace road derailleur. With cables pulling the derailleur in both directions (there is no return spring), the action is always light and smooth. And since there’s no cable housing, there’s nothing to add resistance when the bike gets dusty or muddy. There is certainly some madness in making a custom rear derailleur, but there are good reasons why it works so well. The derailleur is just the last piece of a puzzle, where each individual part makes a very measurable contribution to the bike’s superior speed. There’s a lot more than fits into a short Journal post. We’re not talking marginal gains here, but very real improvements. Taken together, they made this bike so fast on this challenging course.

Far from a retrogrouch fantasy, the Oregon Outback Rene Herse is a state-of-the-art bike that incorporates all we’ve learned over the past 15 years of testing and researching bike technology. There are many great bikes, but few that are custom-designed for covering such a long distance at maximum speed, riding day and night across rough terrain.

In fact, the Oregon Outback Rene Herse works so well that we built a sister bike. That one was ridden by Mark in Unbound XL, and then it won the Arkansas High Country Race (South Loop) and set an FKT (Fastest Known Time) on the Dark Divide 300 bikepacking route. It’s identical apart from the drivetrain, with a 36-tooth Rene Herse one-by crank and electronic SRAM Red XPLR shifting.

Further Reading:

- The full story of the Oregon Outback Rene Herse was published in Bicycle Quarterly 77, and the report from the FKT ride is in BQ 78.

- Aerodynamics of gravel bikes

- The research into what makes bikes fast, comfortable and reliable is published in our book The All-Road Bike Revolution.

- GPS track of the Oregon Outback FKT

Photo credits: Rugile Kaladyte (action photos)