Gravel Myths (3): Wide Tires Need Wide Rims?

In this series, we look at things that you hear from many sources, but that aren’t supported by data and testing. It’s natural to be skeptical when long-held beliefs are challenged—that’s why we lay out the evidence so everybody can evaluate it for themselves. That’s how we’ve always done it, ever since our first tire tests, way back in 2006. Those tests had plenty of skeptics, but in the end they revolutionized our understanding of bicycles by showing that you don’t need narrow tires pumped up to ultra-high pressure to go fast.

“Wide tires work better on wide rims.” That seems to make sense: A wide rim supports a wide tire better, doesn’t it?

The reality is not that simple. For most riders, rim width isn’t a factor they should worry about (within the limits specified for safety). However, there are reasons to choose wide rims in some circumstances, and narrow rims may improve comfort and safety when running stiff gravel tires. Let’s look at this in detail:

Handling

You’ve probably heard that wide tires handle better on wide rims. The idea is that a wide rim makes the tire sidewalls more vertical (left), so they can support the weight of bike and rider better. On a wide rim, the tire is shaped like a ‘U’—whereas on a narrow rim it’s shaped more like an ‘O’ (right). The curved O-shaped sidewalls are easier to flex, hence the idea that a wide tire on a narrow rim is less stiff and doesn’t support the weight of bike and rider as well.

Of course, this assumes you have a stiff tire. With a supple tire, the weight of rider and bike is supported almost entirely by the air pressure inside the tire. The tire itself contributes almost no stiffness. You notice this when you deflate a supple tire: The weight of the bike alone flexes the tire so much that the rim touches the ground.

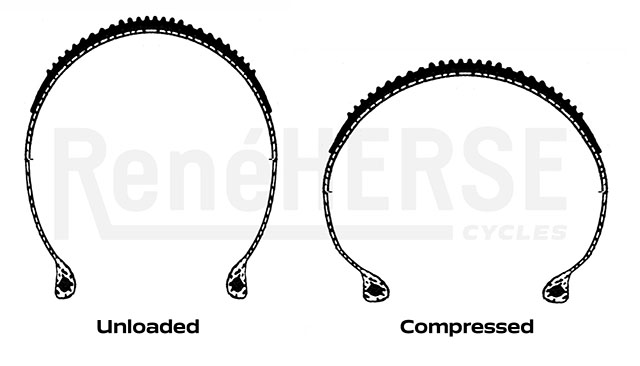

Stiff tires are a different matter—some are so stiff that you can ride them with almost no air. But using the tire sidewall to hold up the weight of bike and rider isn’t necessarily a good idea, even with stiff tires. When the tire hits a bump, it compresses. Then even a U-shaped tire becomes O-shaped (above). So you’re essentially reducing the stiffness as you compress the tire. That makes it easier to compress the tire further, which makes it yet more O-shaped, and so on.

This is exactly the opposite of what you want. The tire sidewalls act like a spring. Any spring should be soft to start with, then get progressively harder as it compresses, so it never bottoms out. Or you may want a linear spring rate, so you can use the entire travel of the spring. What you don’t want is a regressive spring rate: Once the tire starts to collapse, it becomes less and less stiff, and there is nothing to stop it from collapsing further.

I once experienced that on a monstercross bike with stiff mountain bike tires. I ran very low pressures to make the tires less jarring. Everything felt fine in normal riding, but when I cornered hard on bumpy, technical terrain, the front tire’s sidewall collapsed when the tire hit a rock while the fork was turned. It was very sudden, and quite extreme. It took me a while to figure out what had happened: I had experienced a regressive spring for the first time. Once the tire started collapsing, it became easier and easier to flex as it deformed more and more, until the rim bottomed out.

Based on that experience, it seems that using U-shaped tire sidewalls to support the weight of bike and rider may not be ideal even with stiff tires—especially if you’re going to corner hard. Running narrower rims would give you more comfort by letting the tire flex more initially, and it would keep the tire’s spring rate more linear to resist sudden collapse.

(Disclaimer: I have little experience with mountain bikes. There may be factors that don’t apply on pavement and gravel, but which might make wide rims preferable for mountain biking. That discussion is beyond the scope of this ‘Gravel Myths’ series.)

Still not convinced that narrow rims and wide tires can be a good combination? Think about tubular tires for a moment. They are an extreme example of O-shaped tires. Tubulars are perfectly round, and only the very bottom of the tire touches the rim. Tubulars aren’t popular any longer, because they are a bit of a hassle to deal with—they need to be glued onto the rim; they are difficult to repair if you flat—but if you’ve ever ridden them, you’ll know that they are wonderful tires in every respect.

In fact, most pros have been riding tubulars, at least until recently, because they offer such excellent handling. Tubulars absorb shocks better, since the entire tire can flex—it’s not constrained by the rim like a clincher. That’s why tubulars stick to the road and don’t lose traction on small bumps. The idea that the O-shape of a tubular would make it corner poorly is not something you’ll ever hear from pro racers who descend the cols of the Tour and the Giro at breakneck speeds.

(In recent years, many pros have been switching to clinchers, mostly due to marketing reasons, but also because the advantage of tubulars diminishes as tires get wider.)

Rolling Resistance

I’ve heard that wide rims make tires roll faster, but that seems unlikely. After all, we’re running supple tires because they are easy to flex. That’s why supple tires are fast: They absorb little energy as they flex with each wheel revolution or when they hit bumps. So making the tire stiffer by making it more U-shaped seems counterproductive, if you are looking for speed.

Safety

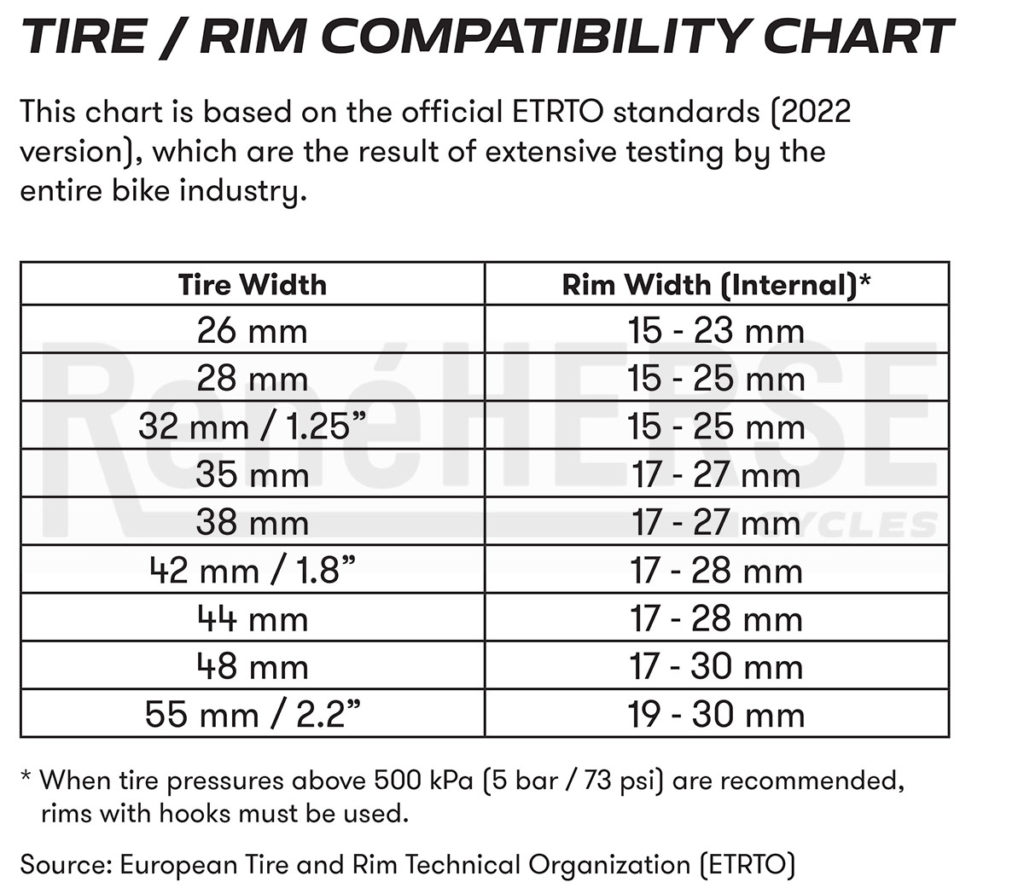

What about safety? Is there a risk that a wide tire will come off a narrow rim? Actually, the opposite is the case: Rims that are too wide can pose a problem. The European Tire and Rim Technical Organization (ETRTO) is responsible for the world-wide standards for bicycle (and car) tires. Their tire/rim compatibility chart (above) is based on testing and input from dozens of tire makers.

Even for 55 mm-wide tires, the chart allows rims as narrow as 19 mm (internal). At the upper end, the limit is much more restrictive, with a maximum rim width of just 30 mm (internal) for 55 mm tires. Why shouldn’t you run wider rims? If your rims are too wide, the air pressure doesn’t push the tire bead outward against the rim, but upward: The tire is more likely to lose pressure or even blow off the rim.

Aerodynamics

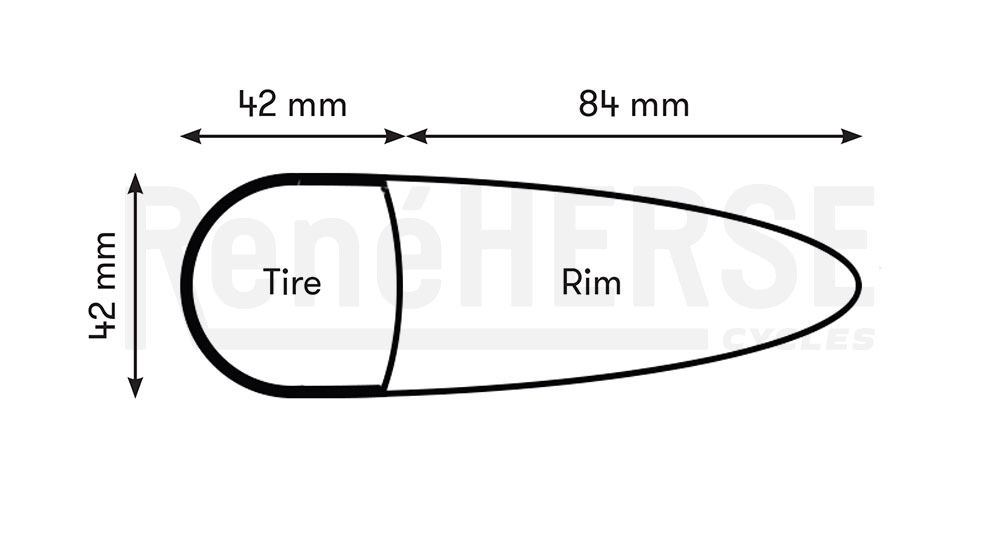

There is one reason why wide rims make sense in some cases—especially for road and time trial bikes with relatively narrow tires. For the best aero performance, the tire should blend seamlessly into the rim. That means the tire ideally should be U-shaped, and the outer width of the rim should match the tire.

That ideal can be hard to achieve that in practice: The rim needs to be narrower than the tire for safety reasons. With narrow tires, this can work, since it’s the inner width that is important for safety, but the outer width that matters for aerodynamics. With a 28 mm tire, the ETRTO allows a rim with a 25 mm internal width, which translates to a 29 mm outer width…

For wide tires, the ETRTO table is more restrictive. For 42 mm tires, the ETRTO specifies a maximum rim width of 28 mm (inside), or roughly 32 mm outer width—some ways off the 42 mm you’d want for optimum aero performance.

You also run into another problem: An optimized aero shape is at least three times as long as it is wide (above). That means the rim should be at least twice as deep as the tire is wide. For a 42 mm gravel tire, you’d need a rim that’s at least 84 mm deep to get any aero benefits. In the real world, that’s not a good idea: A rim that deep would be hard to control in crosswinds. Those are the reasons why aero wheels work well with narrow tires, but provide little benefit for gravel racing.

My Experience

I have a few bikes with wide tires. Some run narrow rims. One is on wide rims. Here’s what I have found on the road (paved and gravel):

My Firefly (above) runs 54 mm-wide tires on 20 mm-wide (internal) rims—close to the lower limit of the ETRTO chart. I’ve never had any issue with this bike’s handling. Quite the opposite: I love the Firefly because its wide tires provide so much grip. On pavement, I can lean the Firefly much deeper into corners than a racing bike. If the ultra-wide tires on narrow rims presented a problem, I would have noticed. (Look carefully, and you’ll see the pannier scraping on the road in the photo above.)

My OPEN × Rene Herse U.P.P.E.R. runs 48 mm-wide tires on much-wider 27 mm (internal) rims. It also rides great. I can’t say that I feel a difference in how well the tires are supported. The wide rims aren’t a problem, but they also don’t provide an advantage.

I do have a bike that would work better with wider rims: My Oregon Outback Rene Herse runs 54 mm tires on 19 mm rims (internal). It’s not the handling that’s the problem, but the brakes. I’m using rim brakes on this bike for a variety of reasons—mostly to run a fork with flexible blades for extra shock absorption. However, the brake pads on cantilevers swing upward as the brake opens. I need to adjust the pads very carefully, otherwise they can hit the tire. Wider rims would eliminate this concern.

Take-Home Message

With supple high-performance tires, you can run narrow rims or wide rims, and you won’t feel a difference. Wide rims make sense on road bikes, where they can improve aerodynamics. But for most of us, rim width is a non-issue.

Photo Credit: Jered Gruber (Image 6; used with permission)

Further Reading:

- Gravel Myths (1): Too much tire?

- Gravel Myths (2): Smaller Knobs Roll Faster?

- Gravel Myths (4): 700C Wheels Roll Faster?

- Gravel Myths (5): Side Knobs for Cornering Traction?

- Aerodynamics of Gravel Bikes

- Click on the images above for posts describing the Firefly, OPEN and Rene Herse bikes

- Results of Bicycle Quarterly’s tire tests

- Our book The All-Road Bike Revolution explores how bicycles really work.