85 Years of Rene Herse Cycles

In late 1938, Rene Herse Cycles was founded out of a passion for making bikes faster, more versatile, and more reliable. In the 85 years since then, this passion has set records and FKTs, won national titles and world championships, and has made cycling more fun for many riders. It continues to inspire us in everything we do, and it allows us to draw on decades of experience and knowledge when we develop our products.

René Herse burst onto the cycling scene with innovative components: cranks, cantilever brakes, a stem and pedals. To showcase the ultralight weight and superior performance of his new parts, Herse entered a bike in the famous Concours de Machines. The Concours was a competition for the best bikepacking bike. Back then, bikepacking was still called ‘cyclotouring,’ but the idea was the same: Develop bikes for self-supported adventures over rough terrain while carrying all the gear you need for exploring off the beaten path.

What was remarkable about Herse’s bike—which he’d built together with his friend, the framebuilder Narcisse—was how light it was: 7.94 kg (17.40 lb) fully equipped with wide tires, fenders, lights, a rack and even a pump. That was a full kilogram lighter than any bikepacking bike before—and it’s lighter than modern bikepacking bikes, too.

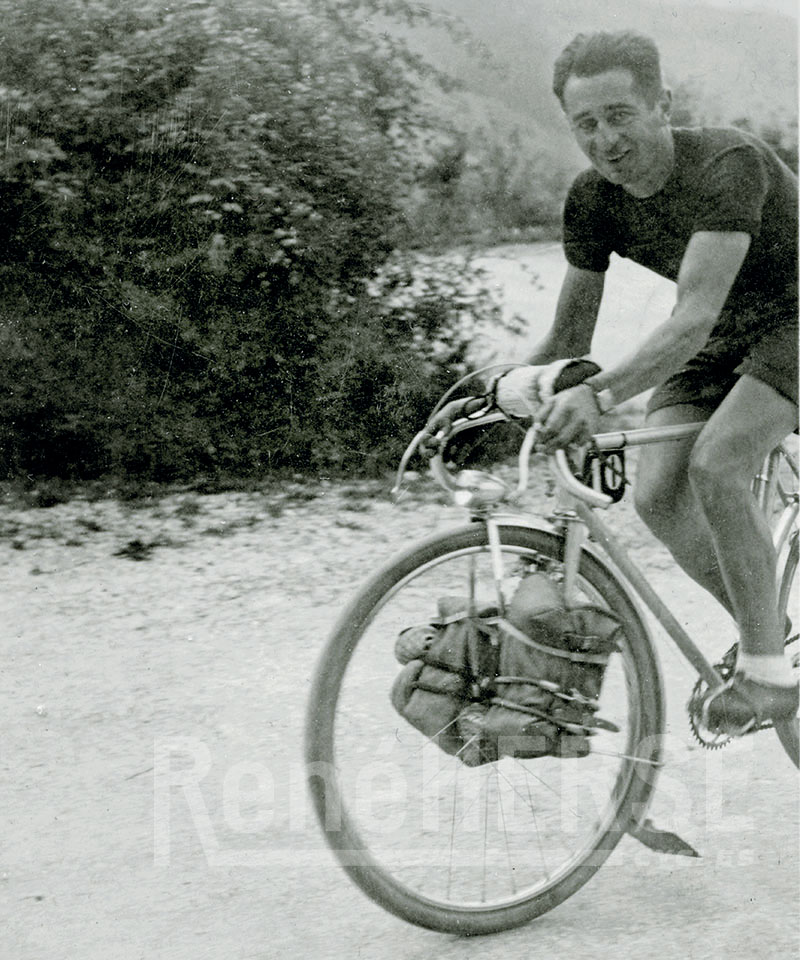

Making a superlight bike was only the beginning: During the Concours de Machines, the bikes were ridden over four stages and 680 km (425 miles) on steep mountain roads, with 11,230 m (36,840 ft) of climbing and descending. In fact, that’s similar to the challenging South Loop of next weekend’s Arkansas High Country Race—a little less distance, but more climbing. Almost the entire course was on rough gravel. The route was chosen specifically to test the bikes to the max. And walking was forbidden, except on one particularly rough section with football-sized rocks. To encourage new solutions for carrying bikepacking gear, the bikes had to 4 kg (9 lb) in addition to any tools, food and drink the riders needed for their journey.

René Herse was a strong rider. Together with his wife Marcelle, he’d already set a number of FKTs on their tandem. He completed the challenging course at an average speed of 21.2 km/h (13.3 mph). He would have won the coveted prize for the best bike, except for some bad luck. At the bike check after the first stage, the inspectors noticed that his bottom bracket had developed play. Of all the parts of his bike, the bottom bracket was probably the only component that he hadn’t either made himself or extensively modified. Adjusting the BB took care of the play, but the penalty points for the malfunction cost him the victory in the Concours. A few years later, he developed his own bottom bracket, with pressed-in bearings that often lasted 50+ years without adjustments or overhauls.

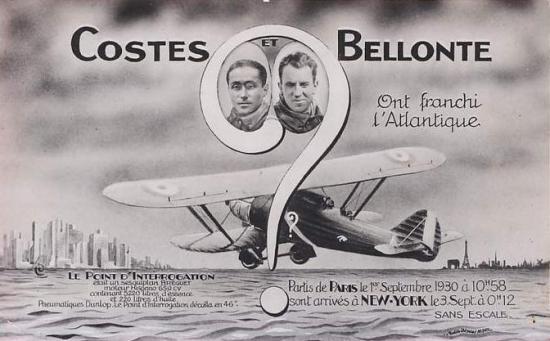

To understand René Herse’s passion and skill, we need to go back a bit further back in time, when he was building prototype aircraft: On September 3, 1930, two French aviators were the first to fly from Paris to New York. That was only three years after Charles Lindbergh had flown the other way. Without detracting from Lindbergh’s formidable achievement, flying from Paris to New York, rather than the other way, meant battling the powerful winds over the North Atlantic. (Even today, flying to France takes one hour less than returning to the U.S.)

Imagine flying in the open cockpit for 37 hours, lashed by wind and rain, while navigating to stay on course to North America! That’s a completely different level of adventure, especially when you consider that 21 (!) attempts to fly across the Atlantic in the western direction had already failed, and five teams had vanished without a trace over the North Atlantic.

The two pilots, Costes and Bellonte (above just after arriving in New York), were feted as heroes on both sides of the Atlantic. Their plane was considered a marvel of technology. It was named “Question Mark” because its mission was kept secret until the last moment, but its nickname was ‘Grand Bidon.’ Essentially it was a huge fuel tank with wings, an open cockpit, and one of the most powerful engines of the time, a 650-horsepower Hispano-Suiza V-12.

René Herse (second from left) was one of the skilled craftspeople who built the ‘Question Mark.’ With others on his team at the aircraft maker Breguet, he made the parts for the plane and assembled it. All his life, he treasured the medal he received after the plane succeeded on its record flight. His daughter Lyli showed it to me when I first met her.

As an avid cyclist, René Herse knew that bikes could be improved by applying aircraft standards. Aircraft have to be light, otherwise they don’t fly. Yet their light weight cannot come at the expense of reliability: If a bolt loosens somewhere over the North Atlantic, you can’t just stop to tighten it. And if a part breaks, it’s usually catastrophic.

René Herse couldn’t have picked a more troubled time to start his business. A year later, Germany invaded France. Herse’s workshop became a refuge for young metalworkers who otherwise would have been deported to work in German armament factories. Herse narrowly avoided deportation himself. To keep all these workers busy, Herse began to make complete bikes that were equipped with his revolutionary components. (The story how custom bike makers in Paris evaded attention from the German occupiers is fascinating all by itself.)

Herse bikes attracted some of the fastest riders. It wasn’t before long that they dominated the results. After the war, Paris-Brest-Paris, the famous 1200 km randonnée, awarded a prize for the builder who had the most bikes with top places. During René Herse’s lifetime, this Challenge des Constructeurs was awarded only seven times (at each PBP), and he won six of them! The only time he did not win was in 1971.

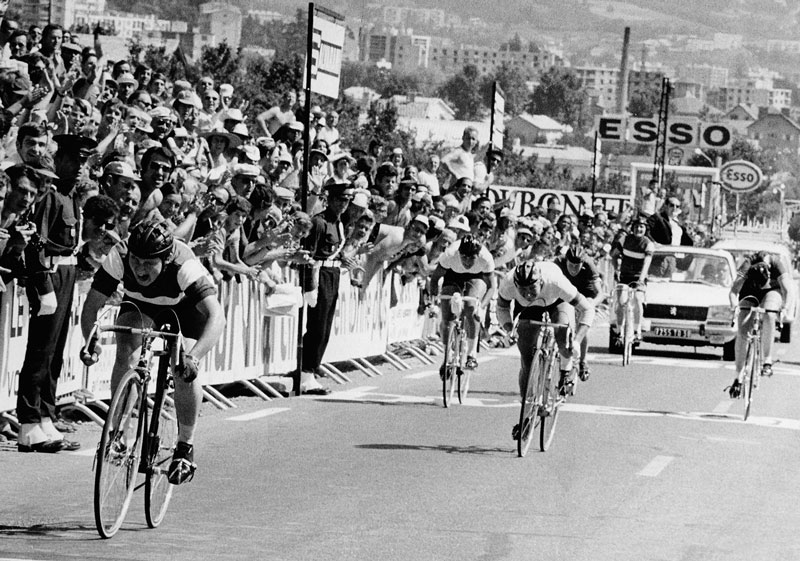

It wasn’t just bikepackers and randonneurs who came to Herse for their dream bikes. Quite a few pros raced on Herse bikes—usually their frames were painted in their sponsor’s colors. With a background in bikepacking, where women always were considered equal to male riders, Herse also supported female racers. His daughter Lyli won 8 French championships. After Lyli retired from racing, she coached a women’s team that won two world championships. Above is Geneviève Gambillon (left) crossing the finish line at the 1972 world’s on her René Herse bike, beating the best riders from the U.S., Britain and Russia.

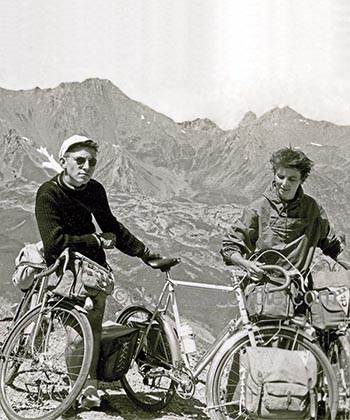

Herse bikes weren’t only built for competition. They also were ridden in amazing adventures. Rides across the length of Europe, or from Paris to Istanbul, required bikes that were 100% reliable. Back then, many countries had no high-end bike shops, and even finding a derailleur cable would have been difficult.

Without all that experience, we probably wouldn’t be where we are today. René Herse knew that supple tires mattered more than anything else on a bike. When most tire makers went to narrower and harder tires in the 1970s, he worked with a small maker to bring back hand-made clincher tires. (We still have a set in our archives.) And when I’m heading to the Arkansas High Country Race in a few days, I’ll be on a bike that’s based on those 85 years of experience of building bikes that are fast, reliable and fun.

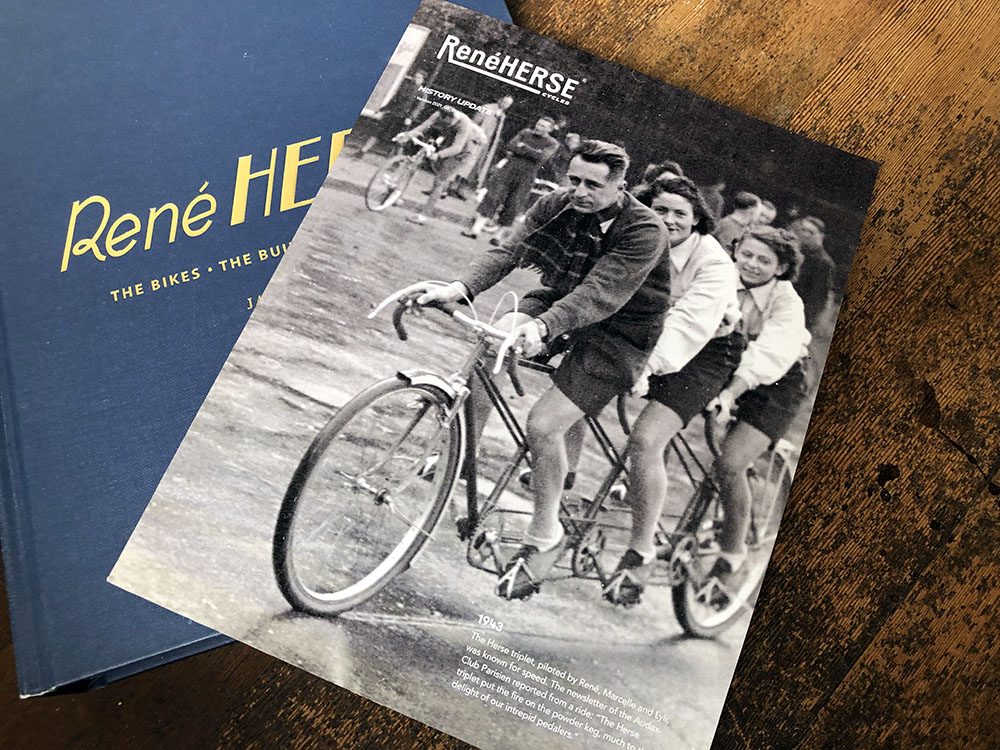

Telling the story of René Herse could fill an entire book. Especially since the Herse archives contain thousands of photos. In fact, that book exists—on 424 pages, it takes you into a world where cycling was not just a hobby, but a way of life.

To celebrate our anniversary, we’re offering the René Herse book at 20% off (including the French edition). You don’t need to be a history buff to enjoy bikes, fashion, adventures and stories told by riders, racers, randonneurs, employees and René Herse’s daughter Lyli. Get your copy, and you’ll spend many enjoyable hours during long winter evenings, diving into the fascinating world of mid-century cycling. This offer is for this week only.

Speaking of winter evenings, we’ve also made a very limited quantity of timeless Merino wool trainers as part of our anniversary offerings. Crafted from the finest Merino wool, these trainers are perfect for cool evenings in camp or for wearing in town. Get one while you can—it’s sure to become your favorite!

Click on the links or images for more information about the book and Merino trainer.

Photo credit: Ansel Dickey (Ted King at Unbound)