Everything Old is New Again

When we were growing up, the year 2000 was short-hand for ‘the future.’ Now we’re a quarter century past that landmark. To celebrate this new milestone, Natsuko and I compiled an (entirely subjective) list of a dozen innovations that have reshaped cycling during these last 25 years. These range from wide tires and disc brakes to GPS routing apps and Strava. We included the caveat that many of these innovations are much older than the year 2000, even if their impact wasn’t felt (or forgotten) until recently. That got us thinking: How old are these innovations, anyhow?

Wide Tires

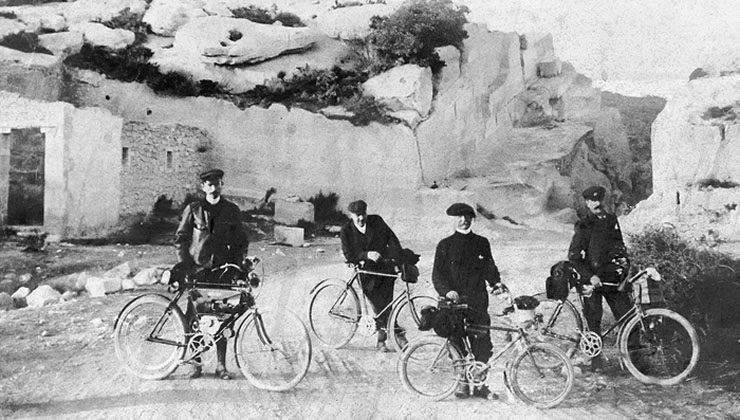

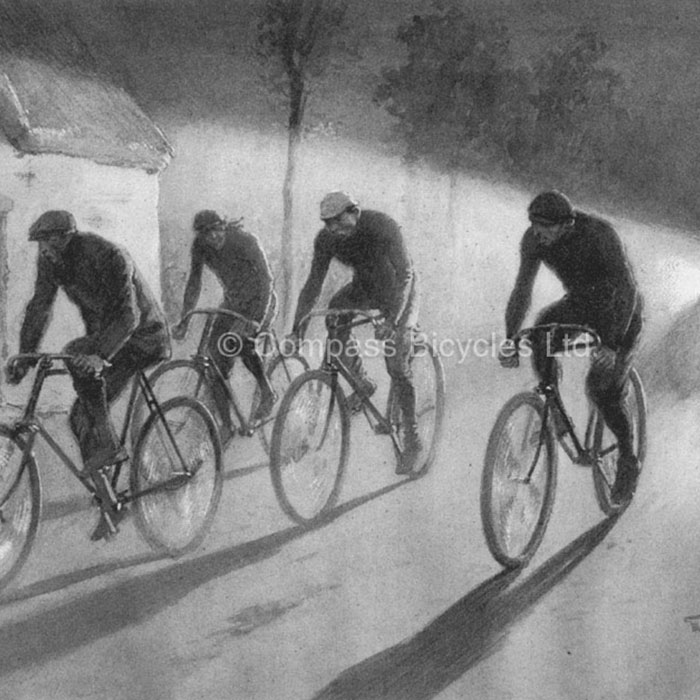

The first pneumatic tires were quite wide. Back in the 1890s, roads were gravel (in the countryside) or cobbles (in the cities), so wide tires made sense. Cyclists still remembered the harsh-riding ‘boneshakers’ with their solid rubber tires. This direct comparison showed that pneumatic tires were faster because they absorbed vibrations, rather than transmitting them to the rider. Wide tires weren’t just better at absorbing vibrations; they also provided a visual distinction to the old-fashioned (and narrow) solid rubber tires. Narrow was out, wide was cool!

How wide were those early pneumatics? When we photographed a top-of-the-line 1890 Humber (above) for our book The Competition Bicycle, we measured its tires: 43 mm—or roughly as wide as modern gravel bikes. Some photos of 1890s racers appear to show tires that are somewhat wider than that. How wide? We’d love to know!

Ultra-wide tires for road bikes became popular in the 1920s and 30s, when ‘Balloon’ tires measured about 48 mm wide. By then, everybody, even the proponents of wide tires, believed that high pressures (and hence narrow tires) rolled faster. The argument in favor of wide tires was that they were much more comfortable and not that much slower. It appears that few cyclists were willing to give up any speed, and tires soon became narrower again.

The discovery of suspension losses (as they apply to cycling) is really a revolution. Where previous generations thought that they had to choose between comfort or speed, we now know that comfort equals speed. Tire pressure has little influence on performance—even on smooth roads—and wide tires are as fast as narrow ones, provided they are constructed with the same supple casings. As a result, today’s tires are wider than ever.

Fun fact: Early riders of pneumatic tires were known as ‘scorchers’ because their speedy tires led them to ride faster and more aggressively than was considered safe and prudent.

Gravel

Nobody claims that riding on gravel is anything new. After all, most mountain roads in Europe were unpaved until the 1950s. (Above our friend, the late Paulette Porthault, on the Galibier in the 1930s.) However, one could argue that these riders rode on gravel because they had to, not because they wanted to.

Even the idea of seeking out gravel is older than this century: Early mountain bikers explored gravel roads. The photo shows Jacquie Phelan racing in the 1980s—on a gravel road. In fact, her Cunningham mountain bike seems closer in spirit and tech to gravel bikes than to today’s mountain bikes. Her tires, by the way, measured 43 mm wide.

Fun fact: Charlie Cunningham custom-bent Cinelli road handlebars to flare them at the bottom, since drop handlebars suitable for his iconic mountain bikes were not available in the 1980s.

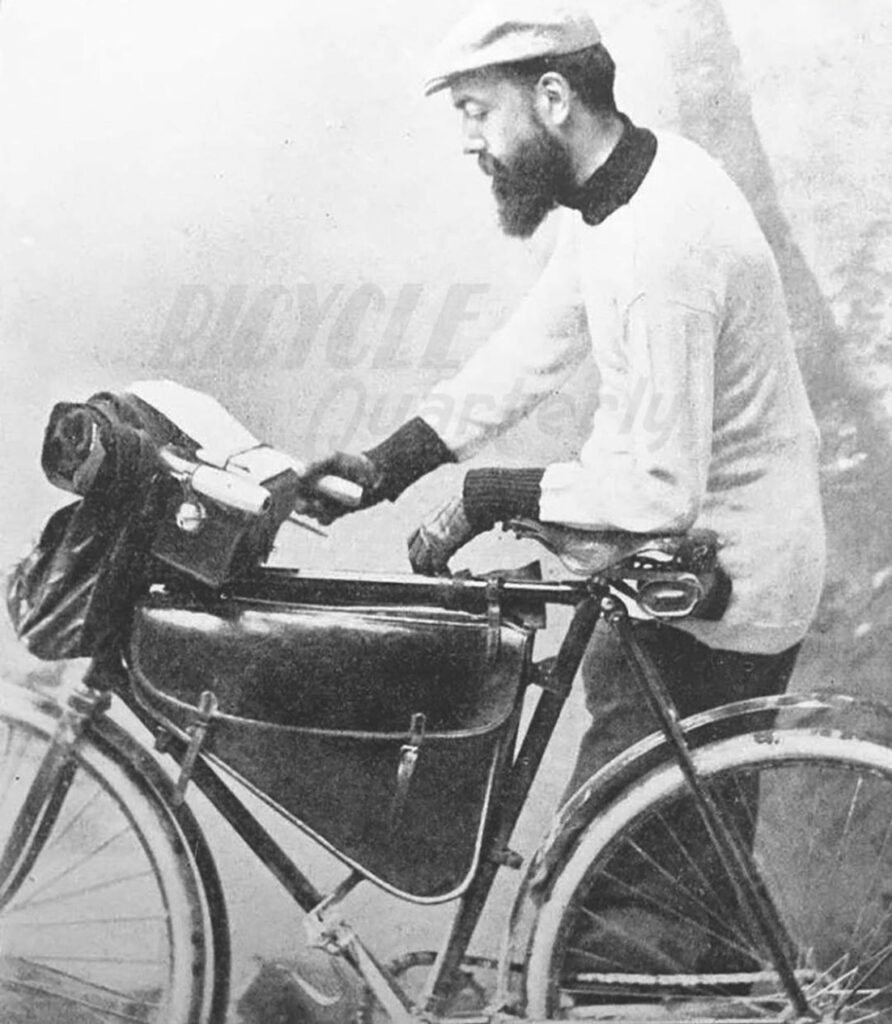

Bikepacking

When cyclists started to use their bikes for travel in the 1890s, there were no dedicated touring bikes. Bag makers offered many types of bags that were strapped to the frame. The materials were different, and there were no zippers yet, but the similarities to today’s bikepacking equipment is remarkable.

The first racks appeared in the 1920s, first to support baskets (made from wicker back then) and rack-top bags. Soon riders figured out that hanging bags off the sides of the rack lowered the center of gravity and improved the bike’s handling. Low-riders and front loads were developed in the late 1930s and became popular in the 1940s.

Is bikepacking on a similar trajectory? Tailfin developed carbon fiber racks to stabilize saddlebags. The company now offers panniers to fit onto the sides of these racks.

Fun fact: When ‘scorchers’ on pneumatic tires began to ‘terrorize’ the roads in the 1890s, some bikepackers extolled the virtues of solid rubber tires: They encouraged a slower riding style, more in tune with enjoying the scenery.

GPS

Before 2000, cyclists navigated using maps, route sheets, and mile markers (above). GPS relies on a network of satellites, and those didn’t exist in sufficient numbers before the 1980s. Similarly, the Internet existed before 2000, but social media—which include RideWithGPS, Strava, Zwift, etc.—became popular only during the last 25 years.

Fun fact: The first hand-held GPS, introduced in 1989, cost $2,900. There weren’t many satellites yet, so it often took many minutes until one passed overhead, and the GPS finally gave a reading.

Smartphones

Smartphones made our list because cyclists now document almost every ride with photos. However, the idea of photographing our outings is almost as old as cycling. Already in the late 19th century, one rider reported with humor: “A few want us to admire their cameras, so groups are formed, photos taken, prints are promised to everybody, which nobody ever receives.”

The revolution lies in the fact that, today, photos are easy to take and easy to share.

Fun fact: Special cameras for ‘cyclo-photographers’ were developed in the 1890s, because conventional cameras were too bulky and fragile for carrying on a bike.

Modern Lighting

Generator hubs have changed how we ride. The idea is almost a century old: Sturmey-Archer introduced their first Dynohub in 1936. Those early hubs lacked power—sidewall dynamos remained a better choice for spirited riding. Racers just used the lights of their follow cars to illuminate the road ahead (above).

As early as the 1950s, observers predicted that powerful generator hubs would soon revolutionize long-distance cycling. That prediction was a little premature. Cyclists had to wait until 1995, when Wilfried Schmidt introduced his SON—Schmidt’s Original Nabendynamo (Generator Hub). LED headlights became available in the 2000s, first for cars and then for bicycles.

Fun fact: René Herse and other French constructeurs equipped their bikes with custom mounts to attach large flashlights. That way, riders could ride without the drag of sidewall dynamos—while the batteries lasted.

Disc Brakes

Disc brakes were invented more than a century ago. If fact, rim brakes are arguably the earliest disc brakes, with calipers that clamp a spinning disc—the rim. Mounting the tire on the disc/rim is a brilliant way of using one part for two different purposes.

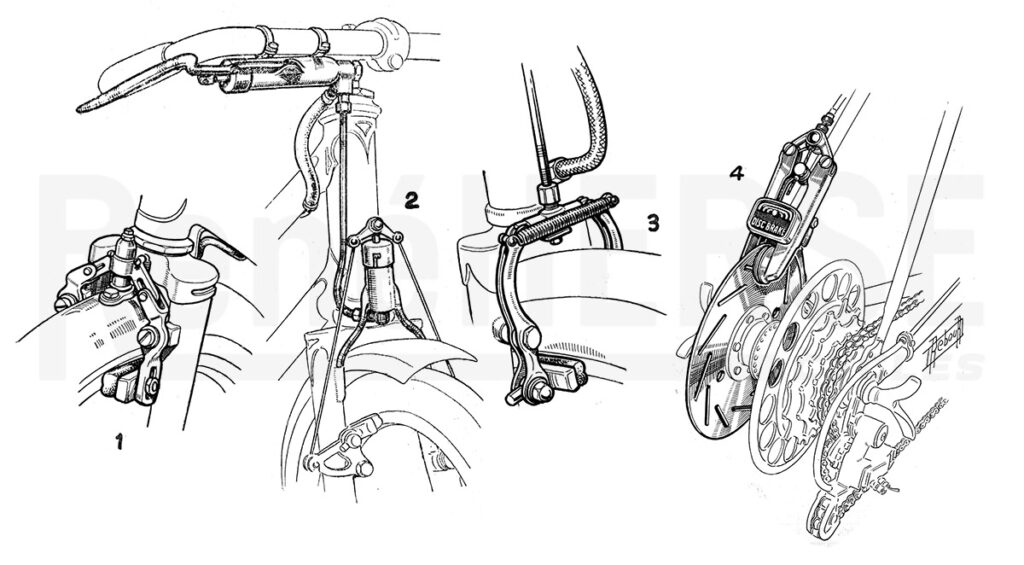

Hydraulic bicycle brakes have been around since the 1940s (above, 1-3)—intended mostly for motorized bikes and mopeds. Shimano showed a disc brake in the modern sense—with a separate, thin disc—in 1972 (above, right). Combining the two technologies seems like a logical next step, especially once mountain bikes became popular in the 1980s. Cars and motorbikes had been using hydraulic disc brakes as early as the 1950s—why did it take until the 2000s for the technology to move to bicycles?

Fun fact: In the early 1980s, Phil Wood made a disc brake that used a composite rotor. It was popular on tandems as an additional rear brake, used during long descents to avoid overheating the rims.

Rando Bikes

Our Japanese and French friends laugh when we mention rando bikes as one of the things that have changed cycling in North America. Rando bikes as we know them were developed in France in the 1930s, then refined further in the 1940s. By 1950, these bikes—with wide 650B tires, integrated fenders, low-trail geometries, handlebar bags, etc.—had already reached their pinnacle. (Above Roger Baumann and Gilbert Lespinasse leading the 1956 Paris-Brest-Paris.) In fact, a 1952 Rene Herse served as the blueprint for a new generation of these bikes in North America and beyond.

Fun fact: During the 1940s, the best rando bikes from Alex Singer, Hugonnier-Routens and René Herse weighed just 10.5 kg (23 lb)—less than top-of-the-line road bikes—even though the rando bikes were equipped with fenders, rack and lights. However, the rando bikes also cost much more than a pro-level road bike.

Tubeless Tires

Tubeless tires found widespread adoption on cars during the 1950s and 60s. Bicycles continued to use inner tubes until the 2010s. Sealing the spoke holes was long considered a problem: Motorcycles adopted tubeless tires when they switched from spoked to cast wheels. With advances in suspension, mountain bikes became faster and heavier—and thus more prone to pinch flats. Airtight rim tape made it possible to run tubeless tires on spoked wheels.

Fun fact: Passenger jets were also late to adopt tubeless tires, perhaps because their tires run at very high pressures (200 psi / 13.8 bar for a Boeing 747).

Electronic Shifting

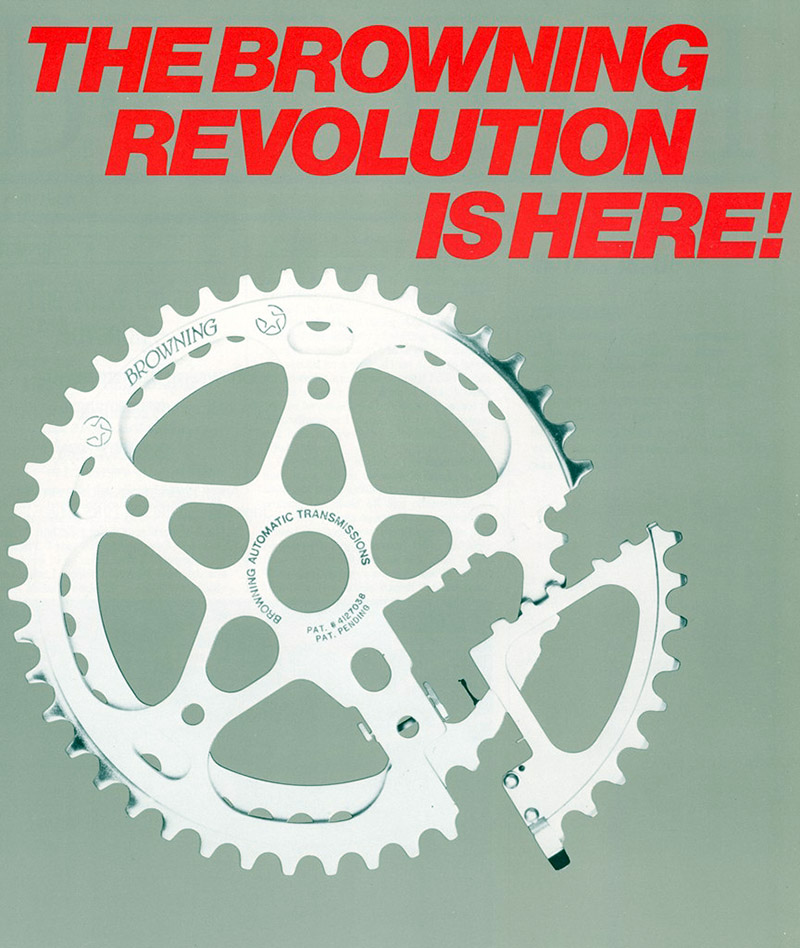

The Browning Electronic Transmission was developed for mountain bikes in the 1980s (above). A segment of the chainring moved sideways and took the chain with it. Those who’ve ridden it report that shifts were very smooth, but that contamination with dirt was a constant problem. This didn’t prevent SunTour from licensing the design and trying to perfect it—without success.

A more conventional electronic derailleur was introduced by Mavic in 1992: The Zap used a tiny battery only to trigger the shift. The chain was moved by a mechanism that was powered by one derailleur pulley. Zap was only for rear shifts: The front derailleur was operated by a conventional cable. Mavic’s electronic shifting had many fans, but Mavic was at best a minor player in the component market, and the mis-matched front and rear shifters probably put off many riders. In 1999, Mavic replaced Zap with Mektronic, now with wireless operation. No longer hard-wired, the technology lost its reliability. Reportedly, radar guns made it freeze up, and it also could stop working in the rain. Mavic decided to stop its component program altogether and focus on complete wheels instead. Zap and Mektronik may not have been lasting successes, but they surely got others thinking.

Fun fact: Chris Boardman led the Tour de France in 1994 on a bike equipped with Mavic Zap electronic shifting.

Wool Clothing

Sheep have roamed the highlands for millennia. Merino sheep, famed for their ultra-soft wool, have been bred in Spain since the Middle Ages. Early cycling jerseys were almost exclusively made from wool (above). Wool jerseys never went away completely, but they fell from favor as synthetics were developed.

Fun fact: The Spanish monopoly on Merino wool was so important that exporting Merino sheep was punishable by death.

Rapha

Mid-century cycling clothing was often quite stylish. In Paris, cycling clubs had their clothes custom-made by fashionable tailors, who were usually cyclists themselves. Like the couple in the photo above, shown with one of the very first Rene Herses. There were concours d’élégance for the most elegant combination of bicycle and rider. All that was forgotten when cycling culture lost out to the dominance of cars. Until Rapha…

In many ways, Rapha was inspired by mid-century cycling—including the name. In the 1950s, Raphaël Géminiani, the strong-willed French racer turned team director, was looking for a way around the prohibition against non-cycling sponsors in the Tour de France. ‘Rapha’ signed up the popular liquor company Saint Raphaël that coincidentally shared his first name. The team’s jerseys carried the liquor maker’s logo, but he claimed that it was just his name. (Never mind the ‘Saint’ part.) It didn’t fool anybody, but somehow Géminiani prevailed, and that’s how cycling became a sport dominated by non-cycling brands. So it’s perhaps fitting that an outsider who decided to change the look of cycling borrowed the name of the pioneer of non-cycling sponsorship. Géminiani himself died last year—I wonder what he thought of seeing his name change the world of cycling.

Fun fact: In the 1952, Géminiani won a hilly Tour de France stage. He credited his yet-to-be-released Mafac centerpull brakes for allowing him to carry more speed and brake later, and thus distance the peloton. Afterward, centerpull brakes dominated in the pro peloton for the next 20 years. For once, racers were ahead of the randonneurs, who adopted centerpulls only in the mid-1950s.

It’s remarkable how many innovations are old ideas that have been resurrected—from bikepacking to gravel racing. Others have taken decades before they became widespread, like disc brakes. And yet others were so revolutionary that they became widely adopted as soon as the technology existed: GPS, but also generator hubs and LED lighting systems.

What about the next 25 years? We’ll probably see a mix of new technologies and old ideas that resurface. Some ideas will migrate from cars and motorcycles—perhaps brakes will be controlled electronically rather than by hydraulics, to allow for anti-lock brakes. Existing tech may finally see a breakthrough, like suspension for gravel bikes. (Above, the lead pack in the 1994 Paris-Roubaix—all with suspension forks.) As to totally new and unexpected ideas, it’s by their nature hard to predict what those will be!

Additional Resources:

- The history of bicycle brakes was told in a special edition of Bicycle Quarterly (BQ 26).

- Two fascinating interviews with Charlie Cunningham and Jacquie Phelan were published in Bicycle Quarterly 29.

- Interested in mid-century rando bikes and cycling fashion? You’ll love our book René Herse • The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders.