Catalogue Specifications and Apparent Bargains

When I started riding seriously while I was in college in Germany, it became apparent that my Peugeot 10-speed no longer was sufficient. Not only did it lack performance, but it required repairs almost daily. So I soon started shopping for a new bike.

Like most new cyclists, I was mesmerized by the latest technology. One rider in town had one of the first Cannondales (above). Its oversize aluminum frame and indexed Shimano components were incredibly alluring to me. But the price was steep, because the U.S. dollar’s exchange rate was high. So I looked for European offerings instead.

I went to the best pro shop in that region of Germany. I asked about Bianchi’s high-end production frames made from double-butted Columbus tubing. From the catalogue specifications, it appeared that they were almost identical as the more expensive “Columbus SL” frames that came out of Bianchi’s famous Reparto Corse race shop. I thought I had identified a bargain.

“Catalogue specs,” said the old racer who owned the shop, with evident disdain. “Does the catalogue show you how much heat they put on the tubes when they braze them? Did you see that the lugs on the more expensive model are much thinner? Do you realize that Bianchi’s best brazers make the Reparto Corse frames by hand, whereas the production frames are made on assembly lines?”

This was a new world to me. I had never considered any of these factors. I went home and thought about this. I began to realize that the apparent bargain frames were less expensive for a reason. Did I really want to invest all my savings into a second-best bike?

Then I got a flyer from the pro shop in the mail, and discovered that the 1989 Reparto Corse frames from Bianchi had gone down in price compared to the previous year’s model. I decided to increase my budget, and returned to the shop to buy the more expensive frame. The owner said: “Ah, the latest Reparto Corse frames were no good. Sloppy workmanship. I sent them all back. But I still have a few older frames, which I’ll sell you at the old price.” I tried to argue that last year’s model should not cost more than the current one, but the shop owner pointed out that once these were gone, there would be no more. So I bought a close-out frame at price that was higher than the current model.

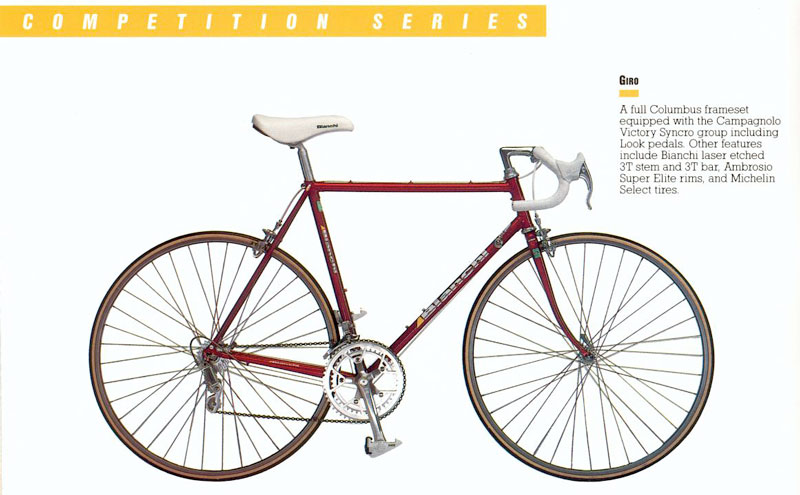

Next we discussed components. I had planned on getting Shimano Ultegra, but I noticed a Campagnolo Victory group on closeout for the same price. I had read that Campagnolo’s new Syncro indexed shifting system worked even with their older components. Combining the new indexing and the closeout group seemed like another bargain to me. “Victory is good stuff, but Syncro is junk,” the bike shop owner informed me. “I don’t even carry it. You don’t need index shifting. You don’t have problems shifting your old bike, and the new components will shift much better anyhow.”

That is how my dream of a mass-produced Cannondale with Shimano components turned into a hand-made Bianchi with gleaming Campagnolo components. The price I paid was the same as the Cannondale would have cost.

Knowing what I know today, I realize that I made the right decision. That Bianchi introduced me to the joys of riding a truly excellent bicycle. It took me to my first race victories and even the occasional tour (above), before it was rear-ended by a pickup truck in Texas, and replaced by an even better hand-made frame. Most of the components were transferred to the new frame, and stayed with me for all my 10 years of racing. They worked as well during my first race, a small beginners’ criterium in Texas, as during my last, the Tour of Willamette, where I tried to hang with professionals who were using this hilly stage race to prepare their European season.

That grumpy bike shop owner really got me off the beaten path of mainstream bicycles. I discovered that an outdated, but top-quality, machine offered at least as much performance and pleasure as the latest state-of-the-art bicycles. Since my new bike already was “obsolete,” I dropped out of the rat race of annual upgrades to newer and supposedly better machines before I even started. This has allowed me to evaluate each innovation on its merits, and to adopt those that truly improve my cycling experience.