How Germans vote

Today, I am reminded of my grandfather in Germany. Not of his cycling exploits during the 1930s, when he rode hundreds of kilometers with his friends on weekends. Instead, I am thinking of him voting.

When my grand-father was in his 80s and confined to his house by severe arthritis, he only left his house when he went out to vote. I remember somebody once suggesting that he stay home, and this usually mild-mannered man became almost angry: “I will go and vote because it matters!” His one vote really did count, because Germany has a system of proportional representation, where everybody’s vote counts. Perhaps as a result, voter participation in Germany is around 85%.

Contrast that with my vote today. I voted at home and mailed the ballot. In the presidential election, my vote won’t be a determining factor since Washington State is not a “Battleground State.” (We do have local issues and our gubernatorial contest can be very close, so I urge Washington State voters to get your ballot in.)

In the U.S., there is a widespread feeling that voters no longer can influence the government in meaningful ways. Only about half of the eligible voters will cast their ballot today. I believe that there are two reasons for this:

- “Winner-take-all” elections have cemented the monopoly of the two big parties. In the last century, no other party has been able to obtain an influential role in government. Many minority interests are not represented in national politics – for example, did you hear any of the candidates talk about environmental protection during the presidential race?

- The basic system of “One citizen = one vote” is not honored. Some senators represent huge numbers of voters, others relatively few. And the candidate who gets the most votes today is not guaranteed to become president.

Proportional representation offers a solution to these problems. Proportional representation means that the popular vote determines the make-up of government, and that minority opinions also are represented in government. My grandfather voted in Germany, which uses proportional representation to elect its government. Here is how my grandfather’s vote worked:

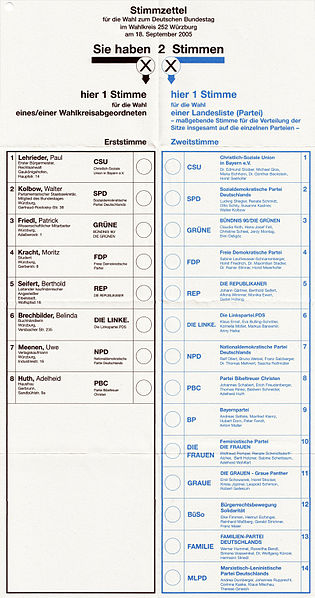

- My grandfather got two votes. One for the “District,” the other for the “List.” You can see the two columns on the ballot shown above.

- The “District” vote (on the left) works like it does in the U.S. for the House of Representatives: Winner-Take-All, the candidate with the most votes goes to Parliament to represent a relatively small district.

- The “List” vote (on the right) is tallied nationwide, and represents the “popular vote.”

- Half the seats in parliament are assigned based on the “District” votes.

- The other half of seats are assigned so that the overall make-up of the parliament represents the popular vote. These seats are assigned based on the “Lists” that each party submits before the election. Combined, “List” and “District” seats equal the percentage of the vote the party obtained. (If a party wins many districts, they get fewer list seats, and vice versa.)

Considering that Americans were heavily involved with drafting the new German constitution after World War II, one might consider the German system an improved version of the older American system. Here is what I like about it:

- Big parties that represent the majority interest take most district seats, just like in the U.S. House. They represent the local interests in parliament. And since the district votes don’t affect the overall make-up of parliament (which is determined by the popular vote), there is little incentive for gerrymandering.

- Small parties that represent minority interests get a proportional minority role in parliament. (In the U.S., they are left out entirely.)

- Every vote counts the same, because the distribution of seats in parliament is determined by the popular vote, not the “district” vote. No small states are over-represented in the Senate. No “Battleground States” that get all the attention of candidates.

- New parties can get elected to parliament (provided they obtain at least 5% of the vote). They can make their case, and if they are convincing, they will get more votes next time around. If not, they vanish again.

Does it work? It appears so. Post-war Germany has been a stable country, arguably more stable than the U.S. in recent years, which has suffered from gridlock and threats of government defaults. Despite this stability, Germans have founded numerous new parties during the last 40 years. The Greens went from a ragtag protest movement to a respected political party that has provided several cabinet members. Die Linken (“The Left”) also have made it into Parliament recently. The Grey Panthers and the German Republican Party have been less successful, but they have influenced the political discourse. The Free Democratic Party (FDP) has been declining as their program lost some of its appeal. The two big parties, the Christian Democrats (CDU) and the Social Democrats (SPD) have ruled in varying coalitions with small parties since World War II. These ample choices encourage citizens to remain engaged in the political process, because change actually is possible. And that appears to be the reason behind the high voter turnout.

Imagine if in the U.S., both Ross Perot and Ralph Nader had made it into the government, together with a small number of others from their parties. Imagine if a vote for them would not have been “wasted,” but rather would have gone toward a coalition that could have ruled the country. I believe this would have been good for our democracy.

There are some moves afoot to change the system in the United States. The National Popular Vote movement is trying to work within the constitution to have the president elected by popular vote. A number of states, including Washington, have passed laws that would make this possible if enough states sign on. This would be a first step, effectively eliminating the electoral college. This would make every state a “battleground state” and ensure that every vote counts. However, it wouldn’t change the “winner-take-all” elections that virtually assure the two parties’ hold on power. Other countries show that it needn’t be this way, and there is no reason why the U.S. system cannot be reformed.

Make no mistake, I love the United States: the country, the people, the culture and the landscape – I chose to live here, after all. But I wish I could take as much pride in my vote today as my grandfather did.

P.S.: This is a rare post that is not related to bicycles. You’d think we only thought about bicycles…