Back Story of RH Mudflaps

When we wrote that our Universal Mudflaps were the result of two years of R&D, some people found that hard to believe. Of course, we didn’t work full-time for 4,000 hours on these mudflaps… but it really did take two years from the first discussion with Ass Savers, who make our mudflaps, to the finished product. We spent countless hours and Zoom meetings drafting design ideas. We provided drawings, they made prototypes, we tested them, and then we discussed how to improve them. Again and again.

The real story of our mudflaps began much earlier, as we developed them over many years of trial and error. Here is the back story of the Rene Herse mudflaps.

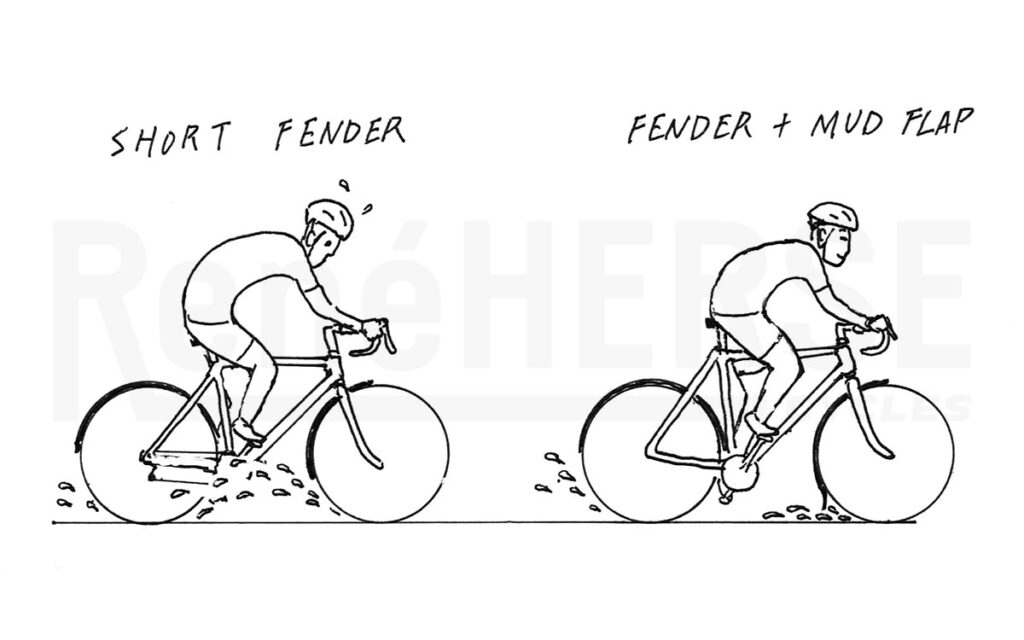

Miyoshi’s drawing from our book The All-Road Bike Revolution shows why mudflaps are important: They intercept the spray from the front tire to keep feet and drivetrain clean and dry. Not shown is the rear mudflap that keeps your friends happy during group rides. It’s not just direct spray: Water caught inside the fenders runs down and gets incorporated into the spray, so fenders without mudflaps will make your feet (and friends) wetter and dirtier than no fenders at all—by concentrating all that water into a single stream. Add a mudflap to a fender with generous coverage, and all that water goes back onto the road without ever reaching your feet or your bike’s chain.

The value of mudflaps has long been appreciated in the Pacific Northwest. When I was racing, many racers cut water bottles in half and zip-tied the pieces to their front and rear fenders. That kept the spray down, but it was neither elegant nor aero. In fact, the half-bottle-mudflaps caught so much wind that they sometimes oscillated until they ripped the (plastic) fender in half.

I like descending at speed, so I looked for something better. A local rider had made a mudflap out of neoprene, attached to the fender with superglue. That worked OK and became my go-to solution.

When we discovered metal fenders, we needed new mudflap ideas. Leather mudflaps (above) were popular for a while, but leather gets more flexible when it’s wet. At high speeds, the spray simply pushes leather mudflaps upward, and they become ineffective. Worse, they flap around and, if they touch the tire, often get sucked into the fender—not good at all. Somebody devised weights that attach to leather mudflaps to stabilize them, but the idea of adding weights to my bike did not appeal. I wanted mudflaps that matched the performance of the rest of my bike.

As I started spending much time at the Alex Singer shop in Paris during my annual visits there, I learned many things from Ernest Csuka, the wizard who had been running the shop for half a century. He made mudflaps from rubber, trapped between the rolled edges of metal fenders. “You could even leave off the screw that holds them in place,” he once mused: “That’s how tightly the rubber fits in there.”

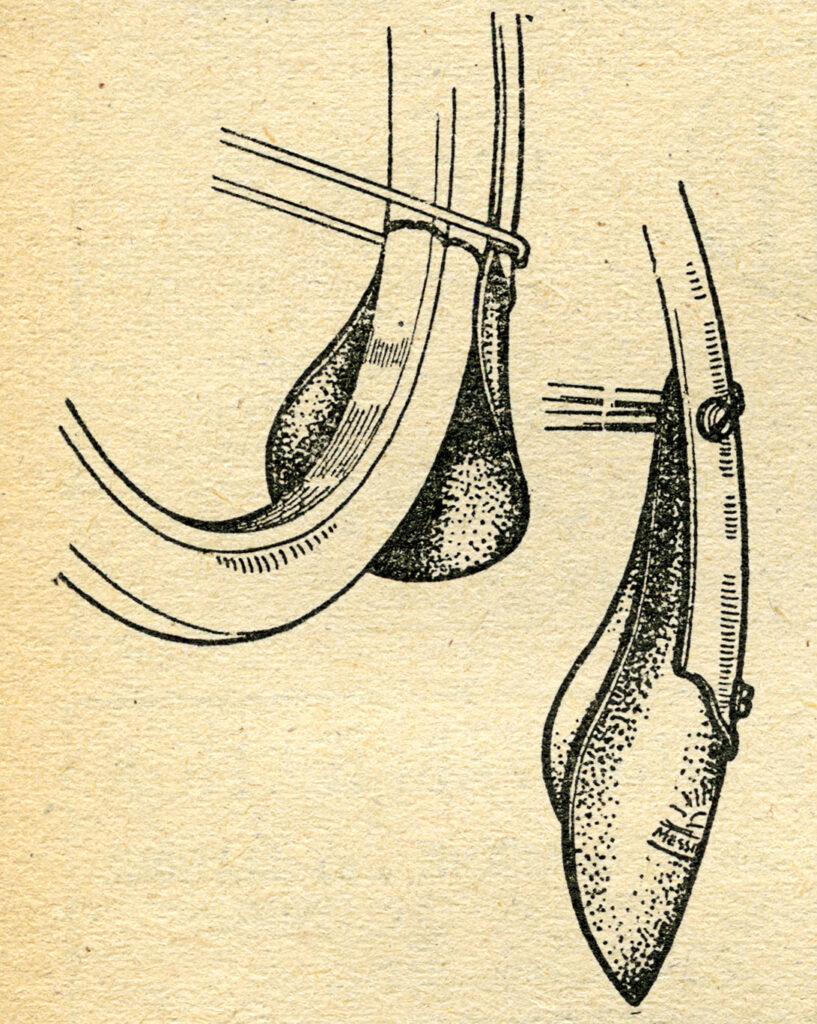

During my research into the history of the mid-century French constructeurs, I came upon this drawing by Daniel Rebour. I loved how the mudflap wrapped around the tire to keep a maximum of spray inside. I noticed the clever attachment via the fender stay screws. But most of all, I realized that mudflaps could be more than just functional. Why not make them beautiful?

Combining Ernest Csuka’s technique and the aesthetics of the Rebour drawing, I experimented with shapes until I came up with something that I liked. From then on, I made my own rubber mudflaps and even wrote an article for Bicycle Quarterly how to make them.

Then I went to Japan and met Natsuko. She took me on a three-day tour to her favorite Onsen hot bath—during a typhoon. The old road in the mountains turned out to be just a footpath… which made for a splendid adventure. There were also plenty of paved roads, and Natsuko’s bike didn’t have a mudflap. Did I mention that it rained hard almost the entire trip?

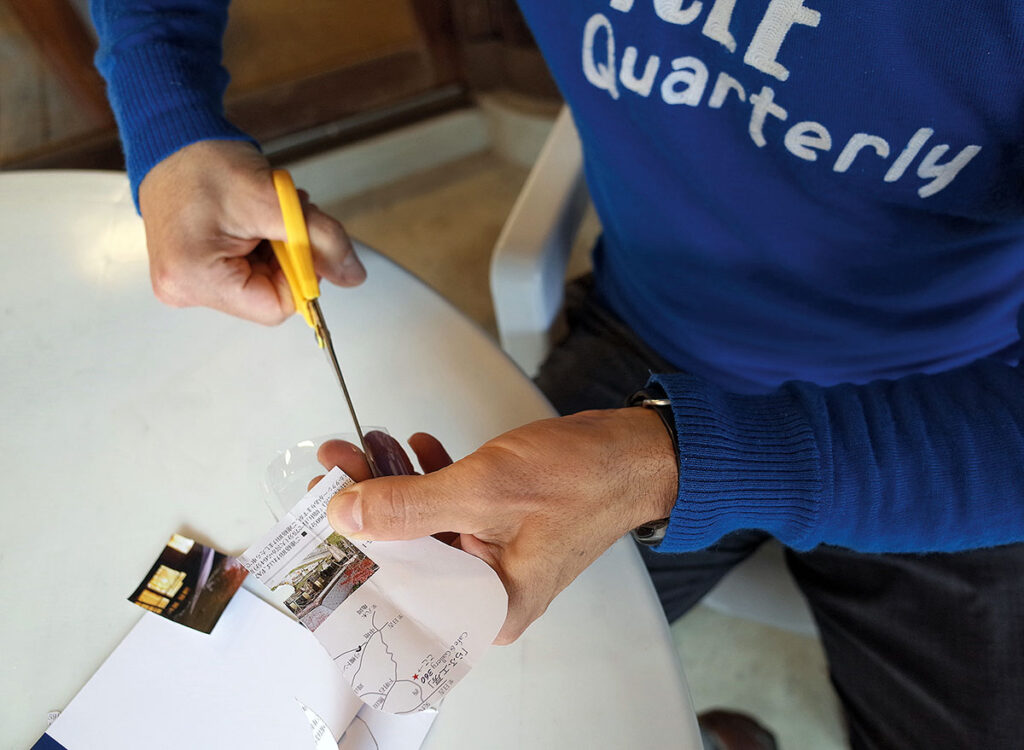

Making a mudflap to keep my new friend’s feet dry seemed like a perfect way to repay the favor for the wonderful adventure she’d organized. We stopped at one of Japan’s ubiquitous vending machines, and I used a soft drink bottle to create a mudflap using the scissors of Natsuko’s pocket knife. It slid into the rolled edges of the fender and stayed in place by friction alone. Once it stopped raining, it was easy to remove.

That mudflap isn’t documented—posing for photos was the last thing on our minds as water was pouring from the sky. In the process, we realized why most plastic bottles have corrugations: It allows the material to be thinner. Less plastic is good, but it makes these bottles useless as mudflap material. Peering into the vending machine, we discovered that Mets soda had smooth-sided bottles, which—after drinking the contents—were perfect raw material for mudflaps.

The photo above shows a repeat performance for another friend, in a hotel lobby equipped with luxuries like cardboard for a pattern and real scissors. (Not to mention a roof over our heads.)

That emergency mudflap did its job admirably, and it was incredibly light. Even so, I wasn’t going to put mudflaps made from old drink bottles onto my bikes, until…

…we went to the Concours de Machines, the competition for the best rando bike in France, with Peter Weigle, the famous constructeur from Connecticut. Peter had pulled out all the stops and built a superlight bike. He had labored day and night for months to create a bike that wasn’t just light, but also beautiful. Peter spent so much time on every detail that the bike wasn’t ready when he had to leave for France. We all worked at the Alex Singer shop, together with Ernest Csuka’s son Olivier, to complete the bike upon its and Peter’s arrival in Paris.

Except the bike had no mudflap. There was rain in the forecast, and, anyhow, our entry for the ‘best rando bike’ really needed a mudflap. And that mudflap had to be superlight and elegant, to match Peter’s amazing craftsmanship. A cut-up plastic bottle wouldn’t do.

My friend Christophe, with whom we were staying at the start of the Concours, pulled out a file folder made from thin black plastic. It was perfect, and Peter approved of the final result. Not only did my feet stay (relatively) dry, but the bike won the technical classification, the prize of the jury, and the prize for the lightest bike.

How light is Peter’s bike? Just 20.0 lb / 9.07 kg completely equipped with rack, lights, generator hub, fenders, pump, bell, even that mudflap—everything you see above, minus the water bottle. It’s a remarkable bike.

The Weigle Concours bike was not created for just that one event. It’s been on many rides and adventures since then. Nothing has broken or worn out prematurely—except the mudflap. Turns out that file folders don’t make perfect mudflaps: The plastic material tends to crack over time. But I loved those superlight mudflaps. They were easy to install (if it started raining during a ride) or remove (for better aerodynamics when it was dry). I wasn’t going back to heavy rubber mudflaps.

We realized that Ass Savers in Sweden had ample experience with making durable, flexible parts out of plastic sheet material. They had been riding Rene Herse tires for years, so it was easy to establish a first contact. They offer custom mudflaps, but that means printing logos and designs onto existing patterns. For our mudflaps, they agreed to make completely new cutting dies. Thank you!

Over the next two years, we worked together to create the mudflaps of our dreams. The shape was refined until it was ‘just right.’ Little cutouts clear the rolled fender edges. Cut lines allow adapting the mudflaps to different fender models. The top with the hang tag is sized so it can be used to secure lighting wires inside the fender—more secure than tape or other methods. We took photos of the installation process and wrote instructions. And then we finally introduced the Rene Herse Universal Mudflap to our customers.

The mudflaps are superlight—just 15 grams. They are strong. Even if you hit them on curbs, they just flex and spring back. The concave shape stiffens them so they don’t flex—no matter how much water is being thrown up by your front tire, and how fast you go. (Full disclosure: We’ve tested them up to 80 km/h / 50 mph. Faster than that, we can’t offer any guarantees…)

Isn’t it pure madness to spend that much time and effort on a simple mudflap? Perhaps—if this was a project undertaken with the intention of making money. All those hours of R&D will never be amortized… But as with so many Rene Herse components, the mudflaps came out of a need that we had ourselves, for our own rides and adventures. For us, every part of the bike should offer the best performance possible—even something as humble as a mudflap. Because it really makes a difference.

When it rains hard, and you’re riding at a spirited pace, dry feet (and a clean drivetrain) are as important as good brake performance—and arguably more important than how fast your bike shifts or how aero your stem spacers are. During the Concours de Machines (above), the average speed required to avoid penalties was high. Even with snow flurries high in the mountains, I didn’t need to stop and put on leg warmers, because my feet and legs were not subjected to the firehose of spray from the front wheel. And the bike aced the technical inspection, because chain and derailleur were not covered in grit. In the end, the mudflap played an essential role in the bike’s success—and in making the event fun for me as the rider.

More information:

- Fenders and associated parts in the Rene Herse program

- Our book The All-Road Bike Revolution not only talks about aerodynamics, rolling resistance and frame geometry, but also fenders and other parts often overlooked when it comes to bicycle performance.

- The story of the 2017 Concours de Machines was told in Bicycle Quarterly 61.