Why Bike Paths don’t always work: A Better Solution

In a previous post, I pointed out that the popular “protected” bike lanes in fact are less safe than cycling on the street: The protection ends where cyclists need it most – at intersections.

To understand what I mean, look at this intersection from the view of a car driver. Imagine planning a right turn in the image above. You approach the intersection, the light turns green, you go.You probably didn’t see the cyclist barely visible in front of the parked silver car. When the car turns, the cyclist will be crossing the street. That’s why today in Seattle, cyclists get a green light a bit before cars. That’s a good first step, but it doesn’t help when the light (for cars and cyclists) is already green. Cars turn, and suddenly cyclists appear ‘out of nowhere,’ since they were hidden behind the parked cars that separate the ‘protected’ bike lane from other traffic.

Here I propose an alternative model for getting more people to cycle without increasing the accident risk. It relies on appropriate facilities for each situation, depending on traffic speeds, intersection density and other factors. The example of Munich in Germany shows that this approach can work well.

Different facilities for different situations

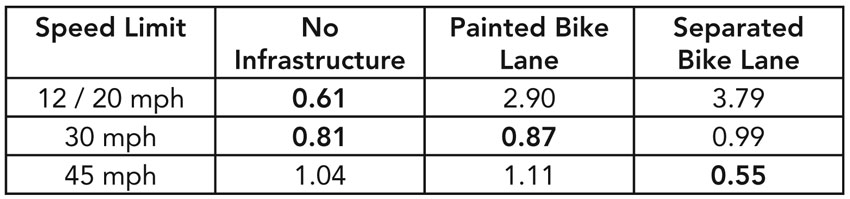

Data from the Belgian city of Antwerp looks at the relative accident risk (with the average risk being 1) on streets based on the speed limits and bicycle facilities:

The speed limits really are just a way of distinguishing different types of streets: Neighborhood streets with low speed limits (12/20 mph), busy city streets with many intersections (30 mph) and major roadways with few intersections (45 mph).

The biggest accident risk occurs in separated bike lanes that run along low-traffic neighborhood streets with many intersections. In this case, riding in the bike lane is similar to riding on the sidewalk, which is known to be the least safe location for cycling.

Generally, where cars are moving slowly, it’s safest to ride on the street. However, on major roadways with high speeds (and few intersections), separate bike lanes are safest.

In between these extremes are streets that have a lot of traffic and many intersections. Here, the best approach lies somewhere between no infrastructure and a painted bike lane. These streets still display above-average safety, but they are not quite as safe as riding on the roadway of low-speed streets or on separate paths along highways with few intersections.

I think this statistic can point the way forward with a multi-pronged approach for bicycle facilities:

No infrastructure at all

- On streets where cars and bicycles move at similar speeds.

- Speed limits must be 20 mph or lower.

- Best for streets with multiple intersections, as it keeps the cyclist in the visible part of the roadway.

- Streets like these also are great candidates for “bicycle boulevards,” which give the right-of-way to cyclists (see below).

- On streets where the speed differential between cars and bicycles is relatively small.

- Speed limit must be below 30 mph.

- Suitable for streets with a moderate number of intersections, as it keeps the cyclist close to the main flow of traffic, hence visible.

- On streets where cars move much faster than bicycles.

- Suitable only for roads with very few intersections, since intersections present a great danger with this design.

Appropriate Design

It is important to realize that there are three parameters that are inter-related:

- number of intersections

- speed limit

- bike facility design

The number of intersections cannot be changed (unless you build bridges and underpasses). It will dictate the design of the bike facility in most cases. The other two parameters, speed limit and bike facility design, should be adjusted to find the best solution for each roadway.

For example, if the traffic speed is too high for a painted bike lane in the roadway, but there are too many intersections for a separate path, then the speed limit should be decreased to make the painted bike lane safe. Fortunately, traffic speeds have to decrease as the intersection density increases, so the needs of cyclists trend in the same direction as those of other traffic. Decreasing traffic speeds a little further will make things safer for all.

With these simple guidelines, it should be possible to design bike facilities that both are safe and feel safe to cyclists. The example of Munich (Germany) shows that it is possible to make cyclists feel safe and get more people to cycle, without pushing them off the street onto separated cycle paths.

Munich and Bicycle Boulevards

Munich, southern Germany’s biggest city, has embarked in recent years on an ambitious program of improving its bicycle facilities. The city has been removing or modifying facilities that have been shown to be unsafe. New facilities are either constructed as painted bike lanes or “Fahrradstraßen” (“bicycle boulevards”, above), which are turned over to cyclists as the main users. Cars are still allowed, but considered secondary users.

Munich also is installing signs that legitimize cycling on the street (above), even where there are separate paths. This is a big deal in Germany, the country that started the trend toward clearing the road of cyclists to provide unobstructed room for cars.

Combined, these measures have increased cycle use in Munich (as a proportion of all trips) by 70% in 9 years. 17.4% of all trips in Munich are made by bicycle. This growth far exceeds that of those German cities where segregated cycle paths remain the preferred option.

It is well known that better facilities, where cyclists feel safe, bring out more people on bikes. Munich shows that this goal can be achieved without segregated trails and without compromising safety at every intersection.

Whereas European cities often do not lend themselves to the creation of “bicycle boulevards,” North American cities provide an ideal setting for streets that are dedicated to bicycles. Here is why:

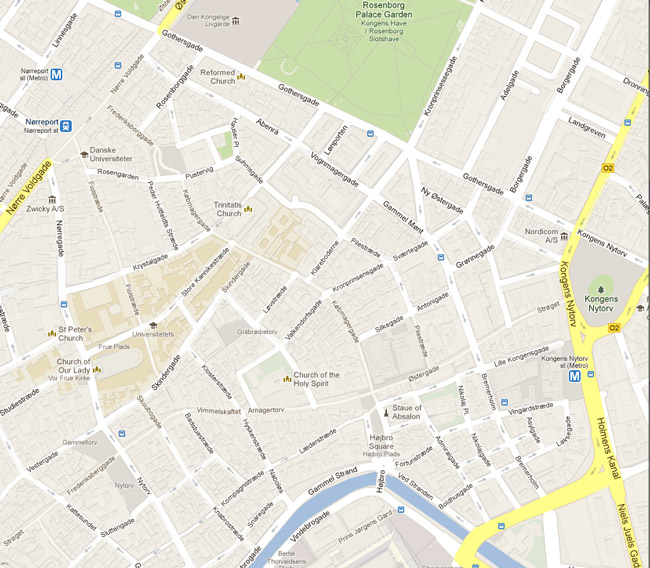

European cities usually have an “organic” street layout that grew over time (Copenhagen shown above). For any given destination, there usually is only one relatively direct route. This means that cars and cyclists have to be routed on the same, busy streets. Creating a “bicycle boulevard” means closing an important traffic route for cars.

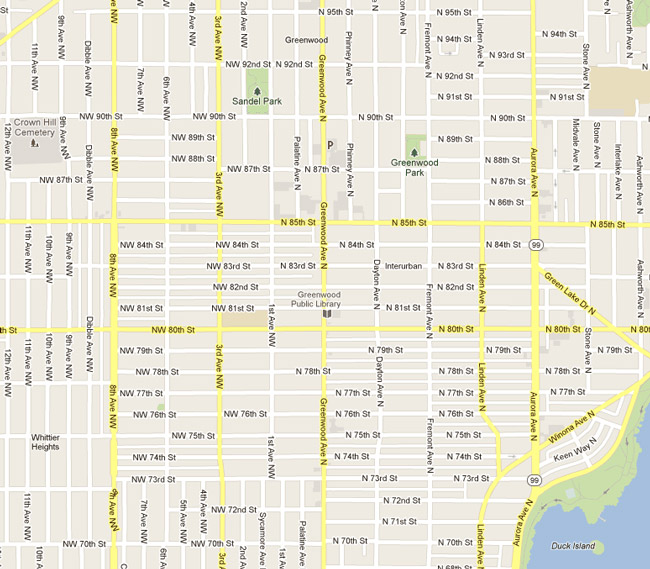

Most North American cities are built on a grid (Seattle shown above), which provides multiple routes for each destination. This makes it easy to provide separate “arterials” for bikes and cars. (The map above shows the “car arterials” in yellow.) Creating “bicycle boulevards” is relatively easy in this setting.

Bicycle boulevards are the ultimate separation, because they channel traffic flow differently for cars and bicycles. Even where bicycle boulevards cross “car arterials”, they do so at right angles, which eliminates the “right hook” and “left turn” hazards. These hazards occur when cyclists and turning cars “share” the same intersection. Where a bicycle boulevard cross a car arterial, either the cars or the cyclists have a green light, so they do not “share” the intersection.

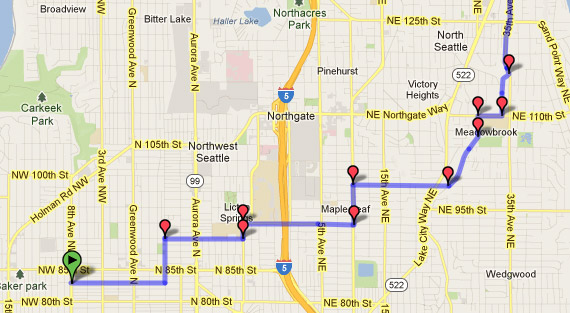

Mark, one of Bicycle Quarterly’s bike testers, pointed out to me that we privately already use what effectively are bicycle boulevards. We have mapped the city to find routes that are fast, efficient and yet away from the main traffic arteries as much as possible (above our northward route). Formalizing these routes as “bicycle boulevards” would be a win-win for all cyclists, and even local residents, who’d enjoy quieter streets and increased safety from cyclists keeping an eye on things.

One thing that is important for efficient bicycle travel is to give bicycle boulevards the right-of-way over cross-streets. Otherwise, they are little different from neighborhood streets with a relatively high accident risk at every intersection.

All we need in North America is the political will to dedicate a few streets – which see little traffic anyhow – as bicycle boulevards. Give them the right-of-way over cross streets, signal the intersections with car arterials, and install appropriate traffic calming devices to sure that cars don’t use them to avoid congestion elsewhere. It’s a relatively simple solution, and we are lucky to have the conditions in place that makes this possible. We could be the envy of Copenhagen cyclists, as they ride on narrow, congested paths and have to deal with turning traffic at every intersection.

Of course, bicycle boulevards cannot go everywhere, so there will still be a need for on-street bike lanes. And separate trails can provide good options in some places. This basic guideline also needs to be adjusted for local conditions.

Conclusion: Better facilities bring out more cyclists. Which facility is best and safest depends on the conditions. North American cities are uniquely suitable for bicycle boulevards, which provide the ultimate in “protection” and “separation” by channeling car and bicycle traffic on separate, parallel routes.

Postscript: For those living in Seattle, the new bicycle master plan, which includes many miles of segregated cyclepaths will be presented at open houses in June. This is an opportunity to make your voices heard. Click here for dates and locations.

Click here to read more posts about cycling safety, cyclepaths and bike lanes.

Photo credit (path along freeway): copenhagenize.com