Bikes in the Age of Tariffs

Today’s post was going to be about a new product we’re introducing—but we need to hold off while we recalculate our prices. You’ve probably seen the news: Virtually all imports into the United States will be subjected to additional, steep import taxes, also called tariffs. The goal is to radically re-orient how manufacturing is done, and to make things domestically. Tariffs tend to be reciprocal, so most countries will increase their tariffs on American-made goods, too.

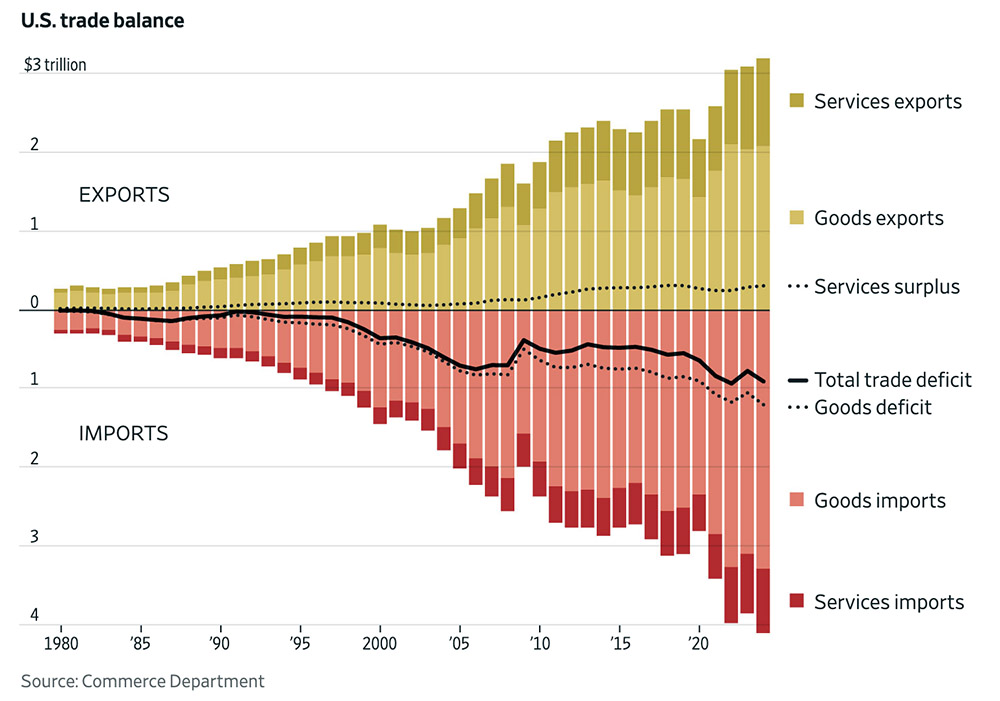

Those behind the new tariffs seem to think that the U.S. imports more than it exports, so the net effect will be positive. Whether that is true is open to debate. Look at the graphic above, published in the Wall Street Journal. What strikes me is how large the volume of imports and exports really is. Sure, there is a trade deficit, but the size of the exports (the green part) is far greater than the deficit. And all that will also be affected by the new tariffs in one way or another.

The bike industry isn’t even an afterthought in these decisions, and yet it’ll be affected deeply by all of them. Let’s look at how the tariffs will reshape our industry and our sport.

What are tariffs?

Tariffs are a tax on imported goods. They are assessed when those goods enter the country, and the importer pays them. Usually, they are added to the freight costs. Shipments are released by customs only after any applicable tariffs (and associated fees) are paid.

Some have suggested that foreign suppliers will pay at least for part of the tariffs by reducing their prices to remain competitive in the U.S. In our experience, that is unlikely. At least in the bike industry, most suppliers are unaware of the tariffs that their good face after leaving the country. They never see them. They calculate their prices based on their cost structure. Even retail giants like Walmart reportedly have been rebuffed when asking suppliers for price breaks to account for part of the tariffs. The simple reality is that in a free market system, only suppliers with lean cost structures survive. There isn’t room for cutting prices by 10, 20, 30% or more.

In summary, tariffs are an added tax on imported goods. Like all sales taxes, it’s regressive, because those with less income spend a larger percentage of their money on buying things.

Existing tariffs

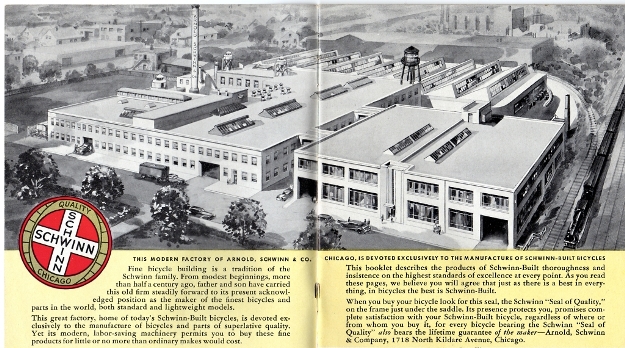

There have been tariffs on bicycles all along. They varied by category, since they were intended to protect domestic producers. Complete bicycles were assessed an 11% tax upon import, but lightweight adult bikes saw only 5.5%. This made sense. Way back, companies like Huffy and Schwinn made the vast majority of kid’s and adult bikes domestically, but high-end bikes were usually imported. The same applied to parts: 11% was the base rate, but parts like freewheel hubs and cotterless aluminum cranks did not have any import duty. Nor did bicycle tires. Because nobody was making these parts in the U.S.

The general idea was to protect certain domestic industries against imports, no matter where they came from. And for things that nobody in the U.S. was making, the idea was to facilitate importing them. As an example, Schwinn made almost everything they needed to build bicycles in their huge Chicago factory (above)—but even they imported derailleurs and other parts for high-end bikes.

A new way to do tariffs

The new tariffs are different: The rates are set not by product category, but by country of origin. Instead of protecting specific domestic industries, the goal appears to be punishing certain countries—and, by extension, American companies that source their products from these countries.

This article is about the impact on the bike industry. How will these country-by-country rates affect the bike world and Rene Herse Cycles in particular?

China — 69%

Tariffs on China have been in the headlines for years. For made-in-China bicycles, a 10% tariff has been in place since the mid-2010s, plus another 25% tariff was enacted in 2018. Yesterday, a 34% tariff was added. If my math is correct, that would put the tariff at a whopping 69%.

However, the impact of the new tariffs on performance bikes will be small. The earlier tariffs added 35% to the price of Chinese bikes and frames. They had the effect of moving most bicycle production out of China, at least for high-end products where manufacturing (and not shipping, warehousing and marketing) makes up most of the costs. One possible exception is the manufacture of carbon frames and components (especially rims), where some companies have significant investments in molds at Chinese factories. Generally, tooling is specific to the machines and techniques of one supplier and cannot be moved from factory to factory, much less from country to country.

Small wheel companies that source their rims in China have put downward pressure on the market for carbon wheels in recent years. (Prices generally have gone down, even though they are still high.) It is likely that the price of carbon rims and wheels will increase due to the new tariffs.

Impact on Rene Herse products: We don’t manufacture anything in China.

Vietnam — 46%

When bike makers moved out of China, many moved to Vietnam. Especially bike assembly—which unlike frame or component manufacture doesn’t require extensive tooling—has moved to Vietnam. Tires and tube manufacture has moved to Vietnam, to be close to the assembly plants that use the majority of these parts. For example, all Schwalbe tires are now made in Vietnam. The new tariffs will add significantly to the cost of these bikes and parts.

Impact on Rene Herse products: We don’t manufacture anything in Vietnam.

Cambodia — 49%

Together with its neighbor Vietnam, Cambodia has become a major hub for bike assembly plants. The tariffs here are slightly higher than those imposed on Vietnam, with the same effects.

Impact on Rene Herse products: We don’t manufacture anything in Cambodia.

Thailand — 36%

Ever since Vittoria closed down its tire manufacture in Italy and moved to Thailand, the country has been a major player in the manufacture of tires. Vittoria’s factories also make tires for other makers, most notably Pirelli. Tires are labor-intensive to make—expect their prices to go up.

Impact on Rene Herse products: We don’t manufacture anything in Thailand.

Taiwan — 32%

Taiwan has long been a center for bicycle manufacturing. When the yen doubled its value in the early 1990s, Japanese products became twice as expensive. Anticipating this, the bike industry had already moved much of its production to Taiwan. Many companies that did not adequately prepare did not survive that transition. SunTour is perhaps the best-known of these. Bridgestone also didn’t move production out of Japan until much later. They ceased all exports at this time.

Since then, Taiwan has become a global hub of bicycle manufacturing, with a complete infrastructure that ranges from companies forging metal parts to makers of bolts and screws. If you want to make high-end bicycle components, you go to Taiwan. Even companies that produce elsewhere, like Campagnolo, import forged parts from Taiwan. Several powerhouse bike companies, most notably Giant and Merida, are Taiwanese.

The new tariff will directly impact the entire industry.

Impact on Rene Herse products: Rene Herse cranks, brakes, derailleurs, stems, headsets and many small parts are made in Taiwan.

Japan — 24%

Japan used to be a global powerhouse of bicycle manufacture. During the early 1970s bike boom, Japanese manufacturers filled the gap when European makers could not supply enough bikes to meet the sudden increase in demand. Industry insiders noted that Japanese production bikes were less expensive and better made than their European counterparts. When the bike boom ended, most distributors cut European bikes from their program and kept Japanese ones. This lasted until the early 1990s, when the ‘yen shock’ (see above) doubled the price of Japanese bicycles and components almost overnight, and the industry moved to Taiwan.

Since then, Japan has kept many of its factories going with a focus on high-end components. Shimano’s top-of-the-line components are made in Japan. A number of mid-sized companies like Nitto and MKS make high-quality components in Japan. Several factories in Japan make high-end bicycle tires for a variety of customers. Since manufacturing costs are relatively high in Japan, the effect of the new tariff will be felt to an even greater extent than mere numbers suggest.

Impact on Rene Herse products: Rene Herse tires, handlebars, racks, frame tubing and some bags are made in Japan. We also import parts from MKS, Nitto and Ostrich.

European Union — 20%

The vast majority of bicycle manufacturing in Europe ended during the 1980s. Companies like Peugeot, Motobecane, Bianchi and Raleigh either started importing the majority of their bikes or went out of business altogether. Component makers like Simplex, Huret, Mafac and many others went out of business or folded into other companies. For example, Huret was taken over by the German Sachs, which then was bought by the American GripShift to form the foundation for SRAM. Of all the storied companies making bicycles and parts in Europe, only Campagnolo remains today.

While mass-market bicycles no longer are made in Europe, small manufacturers make innovative bike parts. There are also ‘legacy’ manufacturers like Berthoud and Brooks who continue to make many products there. Even though the tariff on European goods is smaller than that on Taiwanese and Chinese imports, it is unlikely that bike companies will move to Europe.

Impact on Rene Herse products: Rene Herse TPU tubes are made in Germany. We also import SON generator hubs and lights from Germany, as well as Berthoud saddles from France.

Other countries: 10%

Of all the ‘others,’ only Britain used to be a major manufacturer of bicycles. Today, British companies like Hunt (wheels), Fairlight and Mason (frames) produce their products in other countries. Only Brooks still makes some high-end saddles in Britain. (The majority apparently are made in Asia.) The impact on the lower import taxes for British products is likely going to be small.

Will final assembly of some bikes and components move to one of the ‘other’ countries to take advantage of the lower tariffs? That is unlikely, as those countries generally have high labor costs.

Price increases?

Since the tariffs are assessed on the cost that the foreign supplier charges the importer, and not on the final price in the store, not the entire tariff will be passed on to consumers. How much prices will increase depends on the product category.

Let’s do the math: Take a kid’s bike that retails at a big box store for $ 150. Let’s assume that bike costs $ 30 to make. The rest of the cost is shipping to the U.S., warehousing, transport to the store, marketing, admin costs, customer service, warranty, retailer profits, etc. Whether the bike is made in China, Vietnam or Cambodia, the new 34-38% tariffs will increase the cost by ‘only’ $ 10-12. (The old tariffs are already part of the pricing.) Add overhead and capital costs on those $ 10-12 (financing and insuring the higher purchase price, etc.). Now the price goes up by $ 15-20, or about 10-13% of the final price of the bike.

For high-end products, the calculation looks very different. Manufacturing accounts for a much higher portion of the final price. (Shipping costs are the same for all bikes, and there tends to be less marketing for expensive bikes or components.) This means that the tariffs are much more significant, and the price increase will be greater as a result. Expect to see price increases of 20 or even 30%.

Onshoring?

One of the goals of the new tariffs is to bring production to the United States. As the president said when announcing the tariffs: “If you want your tariff rate to be zero, then you build your product right here in America.”

How feasible is that for bicycles and components? Perhaps the best way to look at this is from a historical perspective.

Mass-market bicycles used to be made in the U.S., and there is no reason why they couldn’t be made here again. Making them requires relatively little specialized technology. The quantities are large, so it may be worthwhile setting up factories to make the bikes and the parts needed for them. However, the impact of the tariffs are also relatively small (see above). Would it cost just 10-12% more to make a bike in the U.S. rather than in China? Even the savings of shipping the bike to the U.S. are relatively small—containers have revolutionized shipping. Most of the transportation costs arise within the U.S. as bikes and parts are shipped from distributors to stores or consumers. Producers may choose to just pay the tariff and keep importing their bikes.

Either way, costs for consumers will go up 10-12%—whether to pay for more expensive manufacturing or for the tariffs. It’s sometimes lost in the discussion that the stated goal of tariffs is to increase prices, so that domestic producers can be more competitive.

For the bikes we love, the onshoring calculation is different. In the days before containers, shipping costs were much higher, and yet the parts for performance bikes were imported. The manufacture of high-end components was dominated by a handful of specialist makers. Until the 1970s, a high-end bike was equipped with Italian (Campagnolo), French (Simplex, Huret, etc.) or Spanish (Zeus) components. Frame tubing came from England (Reynolds), Italy (Columbus) or France (Vitus). Saddles were British (Brooks) or French (Idéale). In the photo from the Simplex factory, crates are destined for the U.S., Mexico, Cambodia, and other far-flung destinations.

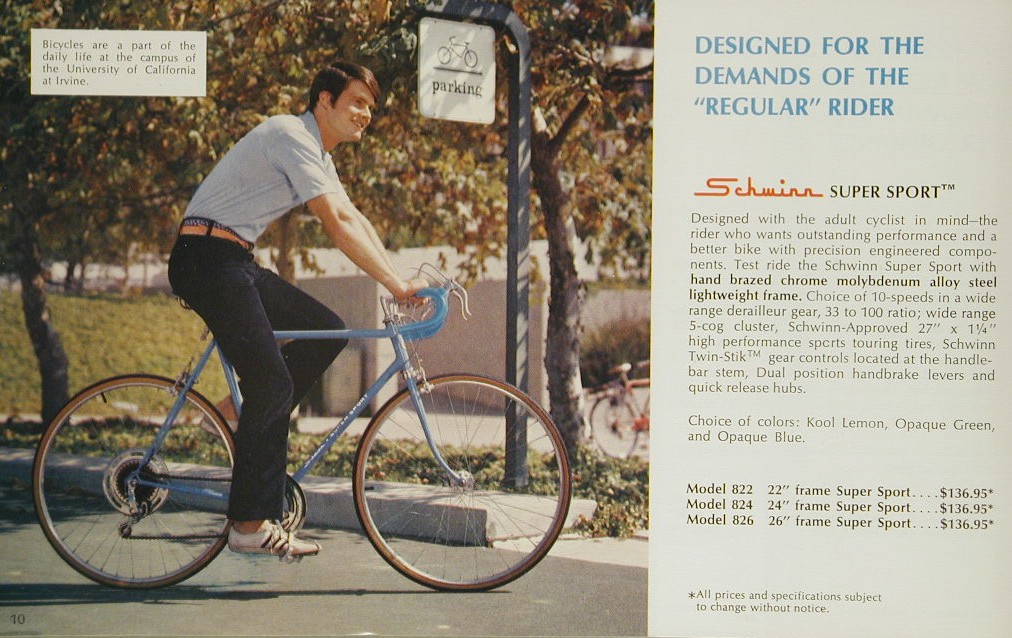

Even ‘made-in-America’ Schwinn bicycles (above) used these parts. Simply put, even on a global scale, the market for high-end parts was small, and the established makers were better and more efficient at making them. American manufacturers saw no upside in trying to compete with them.

On-shoring production today would be difficult and not cost effective. The U.S. has never made high-end bicycle tires or square-taper cranks. Existing manufacturers do not have the specialized tooling and know-how to make these parts. Above is the forging hammer that makes Rene Herse cranks. Note the size of the two workers that are feeding aluminum into the orange pre-warming oven and taking the finished forgings out of the hammer. Machines like this exist only in a few places, and they need to run almost around the clock to be amortized. There is a reason why no forged aluminum bike parts are made in the United States.

When Rene Herse was re-born and we looked into making cranks and brakes, we wanted to source our products locally. Seattle and Washington is home to much of the American aerospace industry, with dozens of companies making parts for Boeing and others. When we approached them, the answer invariably was: “Sorry, we don’t make those kinds of things. You need to find somebody who knows about making bike parts.”

There are a few exceptions, where on-shoring makes sense because it keeps supply paths and lead times short. Rims require only relatively simple tooling and are extremely bulky. That makes shipping and warehousing them expensive. Producing them in the U.S. makes sense.

It may make sense to on-shore bike assembly. Some companies, like Lauf, already have done so to keep inventory lean by assembling bikes on demand. Frames and components require less space, which also reduces shipping costs. The tariffs may create an added incentive that offsets the higher labor costs in the U.S.

Impact for Rene Herse products: A few years ago, we started producing our Rene Herse rando handlebar bags in the U.S., mostly because it allowed us to work closely with the bag maker to get the bags exactly as we want them. Shorter supply paths also guarantee that bags will be in stock without requiring excess inventory.

American companies

Small makers of ’boutique’ bicycle components have flourished in the U.S. for decades. Their heyday was in the early days of mountain bikes, when obsolete (and inexpensive) CNC machines were put to use to make innovative (and colorful) components. Most of these companies fell by the wayside when Shimano began to dominate the market for mountain bike components, but companies like Phil Wood, Paul Components, White Industries and others survived and even thrived. They now have a global following for their parts. Will they benefit from these tariffs? It’s unlikely, because they don’t really face foreign competition: Riders buy them because they are unique and different, not because they offer a better ‘value proposition.’

These American makers export a significant portion of their production. This will be negatively affected once other countries impose their own tariffs. Furthermore, tariffs on aluminum and steel will increase costs, even if these makers use American aluminum. (Price increases for imported aluminum will increase demand, and hence prices, even for domestic aluminum.) Most boutique makers CNC-machine their parts—essentially carving them out of large blocks of metal—which requires a lot of material. Paul Price of Paul Components told us that their biggest cost is aluminum, and they keep only a one-week supply on hand, for cash flow reasons. Expect their prices to increase as well.

A poorer selection

A few weeks ago, I rode with an acquaintance who works as an engineer for Honda, the car company. We talked about his favorite car, the Civic Type R (above). It’s a high-performance version of Honda’s smallest car (in the U.S.) that’s very highly regarded among car enthusiasts and journalists. It’s expensive for such a small car, but everybody who has driven it comments that it’s amazing how good it is, and how every component is optimized to create a car that rivals the very best. It’s clear that the engineers working on this car didn’t just put considerable time and resources into this project, but also a lot of passion. The Type R is the car that every engineer dreams of making, not a car that is born out of market analyses and accounting exercises.

When the subject of tariffs came up, my acquaintance mentioned: “The Type R is made in Japan.” There are slightly different versions to comply with different laws in different countries, but they all roll off the same assembly line. He continued: “There is no way we’d set up a production line for this car in the U.S. We simply don’t have the numbers.” Either the price would have to go up to account for tariffs, or—more likely—the model would just not be offered in the U.S. any longer. And if the U.S. no longer takes a significant number of Type Rs, it’s possible that the numbers for the rest of the world aren’t enough to warrant developing another Type R when the next-generation Civic comes along. In that case, the loss would not just be felt in the U.S, but globally.

That is a factor that’s often overlooked: The Civic Type R—and also many high-end bicycle components—barely make sense from a strict business perspective. The main reason they exists is that the engineers at that company want to make them. International trade has made it possible to pool the global demand for such niche products and make them all in one place, achieving economies of scale that make them (almost) cost-effective.

Splitting production among multiple factories in different countries is standard practice for mass-market products. Honda’s CRV SUV is made in Japan, the U.S., Canada and Britain. But that’s simply not realistic for specialized products like the Civic Type R. It’ll either be made in one place for the entire world, or not at all.

How does this apply to Rene Herse Cycles? It’s no secret that many products in our program exist simply because somebody on our team needs them. We developed 26″ tires in three different sizes because I wanted the 2.3″-wide Rat Trap Pass and its knobby cousin, the Humptulips Ridge, for my bikes. The 1.8″ Naches Pass and the 1.25″ Elk Pass are for Natsuko’s bikes. The same applies to many of our framebuilding parts. If it becomes too difficult to produce these, we may just put aside as many as we need to keep our own bikes running for the foreseeable future. Then these parts will disappear from the program when the remaining stocks run out. In other words, there’s a reason nobody else is making a car like the Honda Civic Type R, or framebuilding parts for rando bikes: There’s no business case for them. The only reason they exist is because somebody wanted to make them.

Conclusion

Mass-market products will see the smallest price increase due to tariffs—because manufacturing amounts to just a small fraction of their final price. They are also the only ones that might be re-shored to the U.S. However, it’s just as likely that companies will absorb the price increase—which amounts to just 10-12% in our example above.

The products that will see the highest price increases due to the tariffs are difficult or impossible to on-shore. They never were made in the U.S., and there is no infrastructure to make them. Prices for these—mostly high-end—products will increase, or they may cease to be offered altogether.

Paradoxically, U.S. makers of high-end bicycle products may also be negatively affected. Tariffs on raw materials will increase their costs. Reciprocal tariffs—and a loss of goodwill toward the U.S.—will affect the exports that make up a significant part of their business.

In summary, for the bike industry, it’s hard to see an upside in the current situation. It’s possible that mass-market bikes will be made again in the United States. For the relatively small market of performance or ‘enthusiast’ bikes, there is simply no reasonable alternative to producing them where the infrastructure already exists—and to consolidate production in one place to achieve the economies of scale needed to make these projects viable. Even domestic producers of boutique parts are likely to see their costs increase and exports diminish.

Many customers wonder: How long until these cost increases happen? With inventories of complete bikes still at record levels, and many of these bikes already in the U.S., it’s likely that the impact on complete bikes won’t be felt for a while. It’s a different story for small companies that tend to be run more efficiently. They keep only limited inventory in stock. Here the price increases may be felt sooner rather than later. At Rene Herse Cycles, we still offer our products at pre-inflation prices. As new shipments arrive, prices will have to increase to factor in the new import taxes. We have already on-shored production where possible, to keep a lean inventory and improved quality control.

To end on a more positive note, the bike industry is full of true enthusiasts, and we’ll continue to find ways to create the bicycles we love. They just may be more expensive in the future, and selection may more limited—but we’ll continue to enjoy the ride.