Bottom Brackets Demystified

Replacing a square taper bottom brackets can seem a bit daunting. What threading do I need? How long should the spindle be? Which taper? It’s really quite simple, and here is how to figure it out.

Threading

The bottom bracket screws into your frame. If your frame was made in the last 15 years, the threading is most likely British (also called BSC or BSA). It’s easy to check: British threading uses left-hand threads on the drive side.

Older Italian frames and some Italianate North American frames used Italian threading. Those use right-hand threads throughout. French frames before about 1985 often used French threading, which also has right-hand threads on both sides.

Key rule for threading: If the drive-side has left-hand threads, it’s British. If both sides have right-hand threads, then it depends on whether your frame is French or Italian. (If your frame is Swiss, then you may have the rare Swiss threading, which also has left-hand threads on the right side.)

You cannot easily convert your frame to a different threading, so make sure you get this right.

Chainline

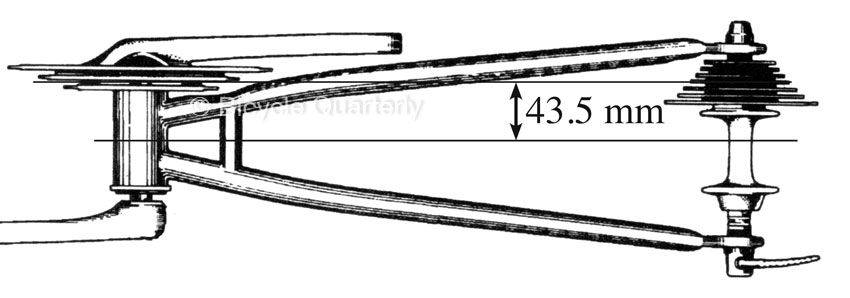

The chainline is the centerline of the chainrings in relation to the centerline of the bike (above). For a double, it’s measured in the middle between the two rings, for a triple on the middle ring. On the rear, the chainline is measured in the middle of the freewheel/cassette.

For most of the 20th century, the chainline on road bikes used to measure 43.5 mm. These days, it’s a bit wider, usually around 45 mm. This ensures that different cranks, cassettes, and frames are compatible.

The chainline isn’t set in stone. Sometimes, makers fudge by a millimeter or two. Triple cranks often use a slightly wider chainline. Some bikes with bowed chainstays to clear extra-wide tires also need to move the cranks outward a bit. However, this means that you will be “cross-chaining” when riding in the big ring and on the larger cogs of the rear cassette. The more severe angle of your chain increases drivetrain wear and noise. It also can lead to poor shifting. This is one of the reason why manufacturers have gone away from triples and prefer compact doubles.

Spindle Length

Since your chainline is constant, your bottom bracket spindle length depends only on your cranks, not your frame (with the exceptions noted above). Depending on the crank design, the spindle length can vary.

Here two examples: A 2007 Campagnolo Record double cranks uses a 103 mm spindle. A TA “Pro 5 vis” uses a 118 mm spindle. Both result in the same chainline of 43.5 mm. How can this be? The Campagnolo crank has curved arms that move the spindle sockets inward. The straight arms of the TA cranks require a longer bottom bracket spindle.

The best way to find out which spindle length you need is by looking up the specs. (The alternative is trial and error…)

Spindle length and the resulting chainline have some leeway. If you are within 2-3 mm of the “correct” 43.5 mm or 45 mm, you are doing quite well. So if you really “need” a 118 mm spindle, but only can find a 121 mm, that isn’t a big deal. It just moves your chainline outward 1.5 mm. (The difference is split between both sides.) A slightly shorter spindle usually is OK as well, but check your clearances before deciding to move your cranks inward. Do you have enough room not only for the crankarms, but also for the chainrings (see drawing above)?

Symmetric spindle?

On racing bikes with relatively large “small” chainrings, you need extra clearance on the driveside, so the small chainring doesn’t hit the chainstays. With a triple, you need even more, because you have the small chainring bolted to the inside of the crank.

To accommodate this, many older bottom brackets have asymmetric spindles. The right side is a few millimeters longer than the left side. This lowered the tread (Q factor) by a few millimeters compared to a symmetric spindle, but it also meant that you sat a little lopsided on your bike. The asymmetry is small compared to the length of your legs, and few riders ever notice this.

Today, most bottom brackets today have symmetric spindles. You can use a small spacer under the right-side cup to create an asymmetric bottom bracket. SKF bottom brackets are designed to be symmetric, but we offer spacers that allow moving the spindle a bit to one side.

Taper

We’ve determined which threading and which spindle length we need. There is one more thing to consider: the taper of the spindle ends determines which crank fits onto your bottom bracket. There are two common tapers:

- JIS: The old French standard, copied by the Japanese. Most Japanese cranks (but not all) and most older French cranks use this taper. René Herse cranks (new and old) use this taper.

- ISO: Campagnolo and many European makers, as well as a few high-end Japanese cranks, use this standard.

ISO and JIS are very similar – the angle of the taper is the same, but the ISO spindle ends are a little slimmer. In a pinch, you sometimes can use a JIS spindle with an ISO crank. To compensate for the wider JIS taper, select a spindle that is about 1-2 mm shorter. The other way around doesn’t always work: A slim ISO taper can extend all the way through the larger hole of a JIS crank, so you cannot tighten the crank.

To summarize: When you specify your bottom bracket, you need to know:

- The threading of your frame: BSC, Italian, French (or Swiss).

- The taper of your cranks: JIS or ISO.

- The length of your spindle in millimeters, depending on the type of crank you use.

With those three factors, you can order your bottom bracket and be confident that it fits. For further information, check out Rene Herse Cycles Bottom Bracket Compatibility Chart (pdf file).