Brennan’s and Adrien’s Tires

When we work with the world’s fastest racers, our main goal is not marketing, but R&D. These riders test our tires to the max, in the real world, under conditions that are impossible to replicate. An essential part of this testing is examining the tires they’ve raced on, so we can see how they’ve fared and where they need improvement. Over the years, that has led to many changes that make Rene Herse tires more durable, without reducing their speed.

Today we’ll have a look at tires that have been pushed far beyond what they are designed to do. Get ready for the good, the bad and the ugly.

Before Brennan Wertz became the 2024 USA Gravel National Champion this year, he raced to P2 in the Sea Otter Road Race. Brennan’s podium finish is all the more remarkable because it wasn’t exactly smooth sailing. As Brennan started the final climb of the race, his front wheel suffered from a broken spoke. The spoke punctured the rim tape, and all air escaped. Brennan recounted what happened next: “The tire stayed on the rim, and I managed to keep the bike upright, but gave up a bit of a gap slowing through the corner to avoid crashing. After a quick moment to take stock, I pressed on, riding the final 3-kilometer climb on the front rim. It wasn’t pretty, but I still managed to hold off the chasers and secure second.”

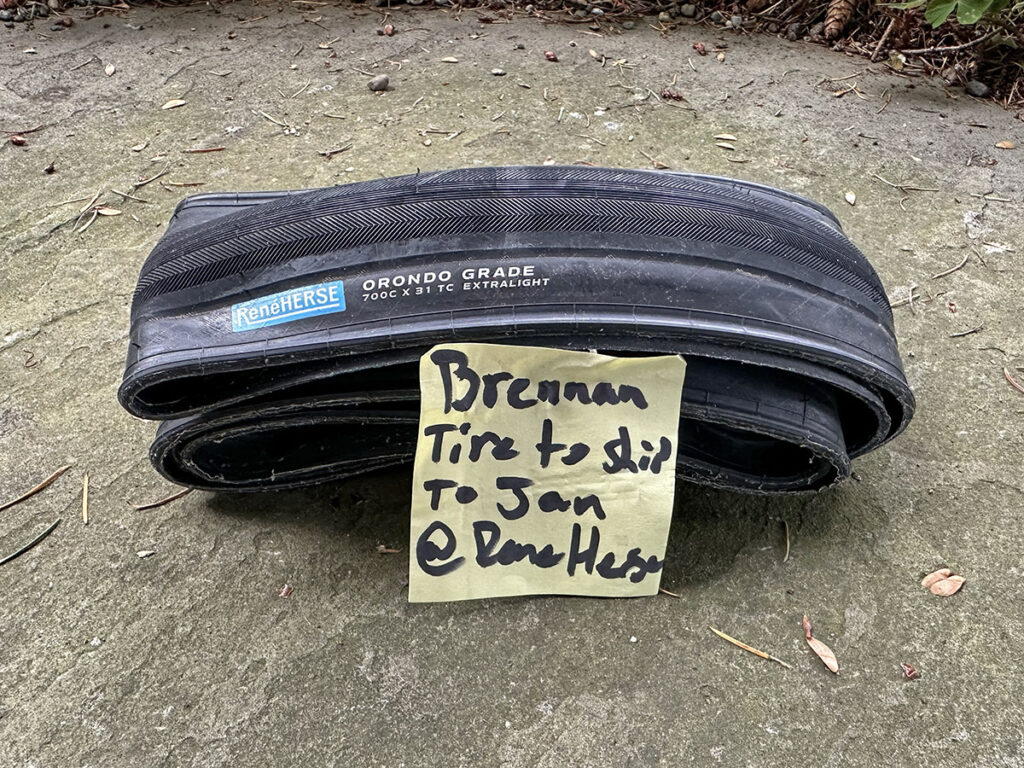

Of course, we wondered about his tire. What happens to a 31 mm Orondo Grade Extralight when a 195-lb racer sprints uphill for 2 miles at 600+ watts without any air? Brennan reported: “The Orondo Grade looks OK, and I might try to set it up again.“ Of course, we told him to send it back. Not just because that’s more prudent, but also because we really wanted to examine his tire.

When the tire arrived, we were surprised. We expected a tire that was practically shredded. What we got back was looking pretty good.

Examining the tire more closely, we can see some scuffs on the tread where the tire skidded over the road. The rubber covering of the casing has worn away in the same spots when it got trapped between rim and road surface. The threads haven’t broken yet, but they probably wouldn’t have lasted much longer. Talk about being between a rock and a hard place—or between a rim and pavement!

The diagonal pattern on the sidewall is a tell-tale sign that the tire was run at very low pressure: At regular intervals, a strand of the casing has broken from the stress. Of course, ‘low pressure’ is a bit of an understatement: Brennan rode a long way with zero pressure.

Surprisingly, there is no visible damage on the inside. The liner that makes the tire airtight hasn’t suffered at all. (The irregularities are residue from the tubeless sealant.)

Would this tire be safe to ride? Let’s put it this way: If I was out on the road, and the alternative was to call somebody to pick me up (or walk), I would install a tube, inflate the tire, and ride home. I’d stop from time to time to check that the damage isn’t getting worse. And I’d replace the tire as soon as I got home (or to a bike shop, whichever happens first).

Of course, we cannot recommend our customers doing this. Fortunately, unless you are a pro racer sprinting for a podium finish, you probably won’t continue riding for several miles after a spoke breaks and lets out all the air. As they say: “Don’t do this at home!” But it’s good to know that even our Extralight casing can survive this type of abuse.

Adrien Liechti send us a set of tires that had seen a much longer adventure. Of all the bikepacking races in the world, the Atlas Mountain Race in Morocco runs over the roughest terrain.

Adrien Liechti and Sophie Potter didn’t just race the Atlas this year. After finishing the 1,300-km (800-mile) race, they continued for another 3,500 km (2,200 miles) across the Sahara Desert and beyond—all on the same tires. Adrien rode 29″ x 2.2″ Fleecer Ridges, Sophie 700 x 48 Oracle Ridges, both with Endurance casings.

Of course, we wanted to know what tires look like after 4,800 km (3,000 miles) in Africa. Adrien agreed to send us his tires. We were almost disappointed when they arrived. There’s not much to see here. Above is the front tire. Apart from wear on the knobs, it doesn’t look like it has suffered much at all. No cuts, no deep scuffs, no fraying of the casing.

The massive mileage and Adrien’s prodigious power are more visible on the rear tire: The knobs in the center are almost worn away.

The insides of the tires looks fine, too. Adrien had zero flats during his three-month adventure.

Looking closer, we see a thorn that has punctured the tire. The thorns of northern Africa are legendary, and now I know why: They are razor-sharp and incredibly hard—basically indestructible. The thorn wasn’t a problem for Adrien, fortunately. The tubeless sealant did its job and sealed the hole.

The diagonal lines you see are a byproduct from how the casing is made—check a new set of tires, and you’ll see that they are present from the beginning. (This is different from the diagonal lines on the outside of Brennan’s tire that indicate too-low tire pressure.)

Adrien’s tires are definitely still safe to ride. If we wanted, we could rotate front and rear tires, and ride them for another thousand kilometers or so, until the knobs are worn all the way down and only smooth rubber remains. (But not any further—let’s not risk blow-outs to squeeze a few extra miles out of our tires!)

Instead, we’ll add these tires to our collection that includes tires from Ted King, Sofiane Sehili, Lael Wilcox, Lauren de Crescenzo and other racers. Sometimes I dream of creating an exhibit with all these tires—strictly for tire nerds like us. Maybe some day…

Photo credits: Mosaic (Photo 2); Sophie Potter (Photo 6)