Disc Brakes in the Tour de France

This year’s Tour de France has had its share of drama, and the winner won’t be the one most observers predicted. Among the sporting achievements, the technological innovation was easy to overlook: Finally, the UCI approved disc brakes, and the Tour is the first big stage race where they’ve been used.

Reading the previews of Tour bikes, it sounded like all racers would make the switch. Just in time for the big race, several big bike manufacturers rolled out new race bikes with disc brakes that approach the UCI-required minimum weight. With no weight penalty to speak of, adopting disc brakes seemed like a no-brainer.

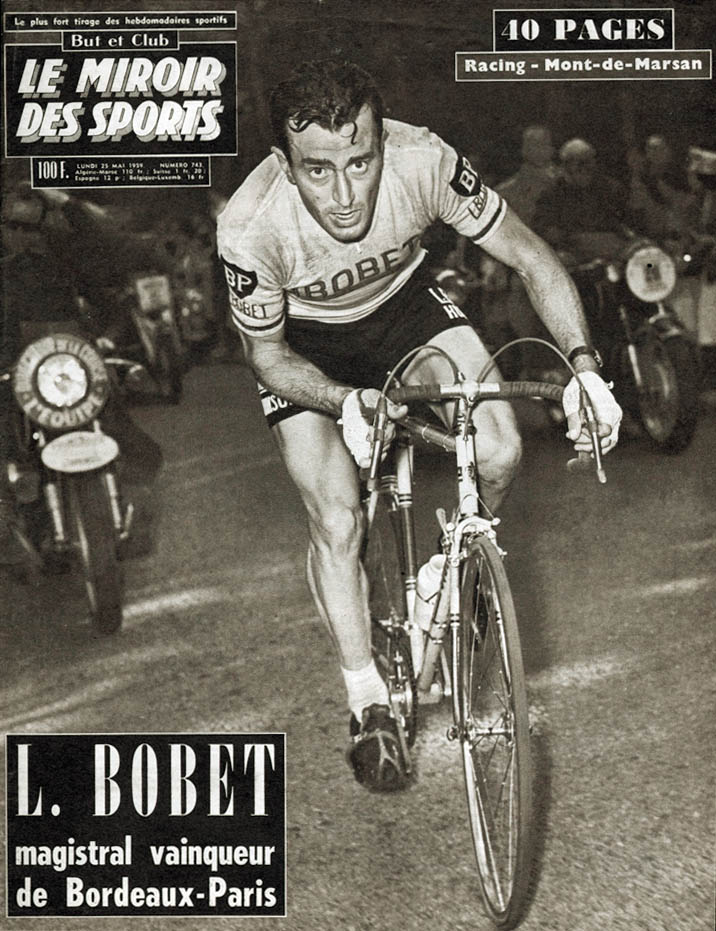

After all, brakes are maybe the most important components of a racing bike. When Mafac introduced their first centerpull brakes in 1952 (above), it didn’t take long until almost all racers adopted them, so superior was their performance. It didn’t matter whether they rode for French, Italian or even the ‘International’ teams – braking hard before the corners was more important than allegiance to national sponsors. And when Campagnolo rolled out their sub-optimal ‘Delta’ brakes, racers refused to use them. Campy backpedaled and resurrected their old sidepulls in a hurry. With disc brakes being heralded as the most important innovation in decades, most expected shiny metal circles to appear on the hubs of the entire peloton.

And indeed, during the first stages, most teams rolled out on bikes with disc brakes (above the finish of Stage 5). Ironically, most of the disc brakes were on aero bikes used for flat stages, where brakes make no difference in the bike’s performance.

As the race continued, most racers quietly switched back to rim brakes. The yellow jersey contenders had used rim brakes from the beginning. Why?

The racers were concerned about flats. Through axles require extra time during wheel changes. Worse, the inevitable manufacturing tolerances change the alignment of the disc rotors on different wheels, even if the same model of hub is used. Unless the disc calipers are adjusted, the new wheel’s rotor will rub. (We realized this during our most recent tire tests, where we thought we could speed up the changes between different wheel sizes, but had to adjust the disc brake calipers after every run.)

BMC Racing found a work-around solution to the problem: When a rider flats, they don’t change wheels, but the entire bike. However, this also means they no longer can use neutral support. Most other teams weren’t willing to run that risk.

When the Tour entered the mountains, many observers expected the racers to switch back to disc brakes.

If disc brakes have an advantage, it’s on the vertiginous descents of the Alps and Pyrenees. Since racers have moved to wider tires with more grip, descents have become much more exciting, with higher speeds and more attacks than in the past. Braking is more important than ever. And yet, there was hardly a disc brake in sight.

What happened? I asked a former mechanic of the French national team. He indicated that the introduction of disc brakes was due to sponsors’ demands. With the big component and bike makers pushing discs, it was useful if pro racers used the new technology.

So why did the racers use rim brakes when their sponsors wanted them to use discs? If discs were superior, racers would have used them, especially in the mountains. After all, a real advantage on the many descents of this year’s Tour would have outweighed the relatively small risk of losing time due to a wheel change.

The answer is simple: Really good rim brakes stop just as well as even the best disc brakes. And many riders find that rim brakes offer superior feel: The brake lever is directly connected to the rim via a cable, rather than having the feedback dulled by the wind-up of the spokes and by hydraulic fluid. It’s refreshing that even today, where bike racing has become big business, winning races still is more important than pleasing sponsors.

In the future, I expect that the problems with wheel changes will be overcome by standardizing the disc location. A friend has already done this, using thin washers to make sure all his wheels fit all his bikes without adjusting the brakes. It’s a lot of work, and team mechanics will not be happy…

Rotors will also have to be standardized – currently, teams use both 140 and 160 mm on the front – to simplify neutral support. And then, the sponsors finally will be able to showcase bikes with disc brakes in the Tour. For now, it’s clear that disc brakes don’t offer a big advantage over the best rim brakes.

Back in 1952, it was different: Centerpull brakes swept through the pro peloton. With their pivots placed next to the rim, they offered greatly superior stopping power and modulation to previous brakes. In fact, the rim brakes that dominated the 2018 Tour de France use the same principle – only the actuation is different to eliminate the need for straddle cables and cable hangers.

Further reading:

Photo credits: A.S.O./Tour de France.