Flèche Northwest: 24 Hours, Mostly Rainy

“Le tandem avale la distance,” I thought as we pedaled through the night. “The tandem gobbles up the distance.” Long stretches of road seemed to be compressed during the weekend’s ride, with the difference being that I wasn’t riding my own bike, but rather sitting on the back of a tandem.

We choose to include a tandem this year for our annual Flèche Northwest 24-hour ride. We were a team of five friends, and our course took us counterclockwise around the Olympic Peninsula.

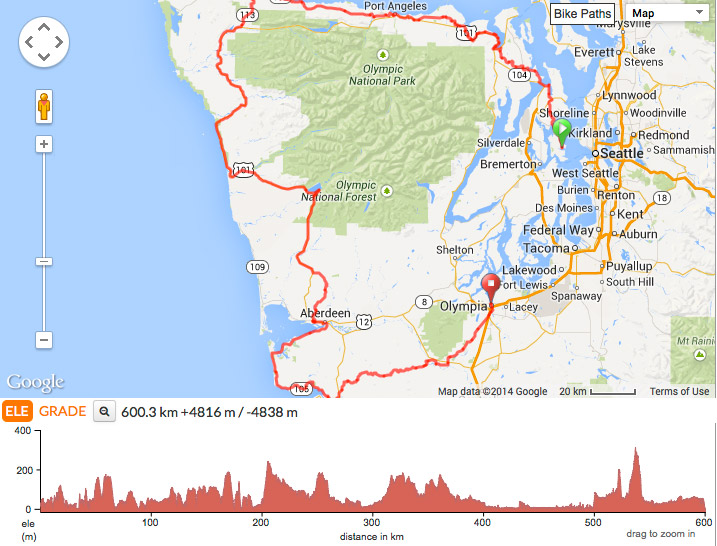

It’s a course that takes us far from civilization and traffic. It feels like a real accomplishment when you can trace your ride on a map of the entire continent… You can see the course here – but beware that “Ride with GPS” appears to overestimate the elevation gain by a considerable margin. It’s a hilly course, but not that hilly.

We met in downtown Seattle. It’s not as romantic as the traditional start of the French Flèche Vélocio in front of Notre Dame in Paris, but it’s still neat to leave the city, and the next morning find ourselves on the other side of the Olympic Mountains by the beaches of the Pacific Ocean.

We started with a pre-ride meal. This year, there were only four bikes, since Mark and I were riding a tandem. My broken hand is healing well, but I wasn’t sure whether holding onto the handlebars for 24 hours was going to be good for it. In addition, we love tandems, and I hadn’t ridden one with Mark in a long time.

We took the ferry to Bainbridge Island, then waited 15 minutes for the ferry traffic to get out of town. Fifteen minutes wasn’t quite enough – tandems really do compress space and distance. By the time we had crossed Bainbridge Island and headed across Agate Passage, we had caught up to the traffic. The weather was still nice, but the windsock indicated that we had a blustery ride ahead. Fortunately, we then turned off the highway and only saw a handful of cars during the next few hours.

One advantage of being on the back of the tandem is that I was able to take photos while riding…

Clouds had moved in by the time we crossed the Hood Canal. The forecast was for a 70% chance of rain.

We enjoyed the backroads of the Quimper Peninsula. The uphills were a great time to chat and catch up. On the flats, things were less social because we were going a bit too fast and the wind made too much noise. We didn’t have a computer on the tandem, but one of us later uploaded the ride to Strava. We found that we were cruising at about 36 km/h (22 mph) on the flats – into a headwind. The three riders on single bikes needed to use their best drafting skills, otherwise, they stood no chance of keeping up.

The weather forecast – 70% chance or rain – turned out to be optimistic. It started with a thundershower that doused us with huge raindrops. They surely must have been hailstones not long before they hit us, they were so large and forceful. Fortunately, we had added all kinds of mudflaps to our bikes, so neither our pace nor our spirits were much dampened by the deluge. Then the clouds tore apart for a few minutes to give us a spectacular sunset.

Riding on the shoulder of a busy highway in the rain greatly increases your risk of flats. The almost inevitable happened: A piece of steel wire punctured the rear tire of the tandem. With four able-bodied riders, it didn’t take long to remove the wheel and tube, but it took considerably longer to get the little steel wire out of the tire. We often have talked about bringing tweezers, but I think now we’ll really start doing so. A pocket knife finally enabled us to dig out the offending wire without damaging the tire.

After a brief resupply stop in Port Angeles, we were swallowed by the night. We passed a house or two every few hours, but otherwise, it was dark. I had been navigating, but that task was easy now: “At the next T-intersection in about three hours, we turn left, then merge with Highway 101 two hours later, and turn left again around 7:30 in the morning.”

With nothing to do except pedal, I was free to daydream – or should that be “night-dream”? Time went by much quicker than it ever has on a night-ride.

Before I knew it, we had climbed the ridge overlooking the Strait of Juan de Fuca – did I mention that the tandem climbed very well, too? The twisty descent always is fun at night. With the new generation of LED headlights, it was twice as much fun this time. At the bottom, we heard the waves lap against the shore, even though we could not see the water in the darkness.

The rain had stopped, and we saw a sliver of moon overhead, as well as many stars. We seemed to fly through the night. When I sat up to stretch my back, I was surprised how hard the wind blew into my face. Either we were going very fast or the headwinds were quite strong. In fact, it was a combination of both.

One of the modern bikes developed a shifter problem, so we stopped in Forks, the only place with a 24-hour store on this side of the peninsula. We got some lubricant and took a quick break. It was 1:30 a.m. when we rolled out of town. Several pedestrians did a double take as our paceline of four bikes, led by the tandem, cruised through this remote logging town in the middle of such a blustery night.

As the new day broke, we reached Lake Quinault. Usually, we have breakfast here, but the historic lodge opens only at 7. It was just after 5, so we signed our cards, then continued our ride.

We had been lucky, and the night had been mostly dry. Now the clouds made up for lost time. It was pouring. Hahn spotted the “OPEN” sign on the Humtulips store, and we stopped for a warm drink and snack.

The storekeeper, like so many on this ride, was delighted by the change from her usual routine, and practically adopted us for time we spent there. We learned that Humtulips means “hard to pole,” referring to the challenges the Native Americans faced when poling their canoes up the river here.

Alas, our hope that the rain was just a shower turned out to be optimistic, and after 15 minutes, we headed out into the deluge. At least traffic was light, so we did not have to ride on the shoulder, where we’d have risked more flats.

Our real “resupply” stop came in Aberdeen, after 411 kilometers. Our handlebar bags were empty black holes, since we wore all our clothes and had eaten all our food. The local Safeway grocery store had a café that provided hot drinks and oatmeal. We bought Ensure Plus meal replacement drinks and chocolate for the road ahead. It wasn’t quite the same as the usual, civilized breakfast at Lake Quinault, but it fueled us for the second portion of the ride.

From Aberdeen, we headed south along the Pacific Coast. The strain of riding in wind and rain for 16 hours with no real stops began to show on my companions’ faces. Steve Frey is doing a great job drafting, so he is hidden behind Steve Thorne (left). Hahn (right) is taking a break from having to focus on the wheel in front. In a paceline, you get to rest mentally when you are at the front, but with the tandem leading the way, the other three never got to the front, and thus never got to rest. (Life can be unfair – I could rest the entire way.)

The wind was still unfavorable to our progress, and without the tandem, it would have been tough going. The surf on the shore of Willapa Bay was much higher than I’ve ever seen it. Fortunately, our tandem has a much shorter rear top tube than most modern machines, and it sliced through the wind without much trouble. We truly had twice the power with the same wind resistance as a single bike.

Vélocio once wrote how riding through the night made you appreciate the things you see much more “because your senses are amplified through the effort of riding.” The trees lining the roadside and the hills with their fresh green of spring did seem much more amazing than they usually are. I was having a great time.

We made another stop at a convenience store in Raymond, where we stocked up for the next 80 km (50 mile) without services. Five minutes later, we stopped again to sign our cards for the 22-hour control. We had ridden 501 kilometers, yet the most challenging part of the course was still ahead.

We headed into the Willapa Hills, where we faced two long climbs (and descents) on gravel roads. A few years ago, we were held up here by a car rally, but this year, we had checked to make sure the roads were clear. In years past, our friends from Olympia had acted as spotters and provided us with updates on the road conditions, but this year, we were winging it.

We had equipped the tandem with 38 mm-wide tires, but when you consider the weight of both riders, that isn’t very wide at all. We later calculated that in order to get the same air cushion as we do on our single bikes with their 42 mm tires, we’d need 60 mm-wide tires on the tandem.

This means that there are no photos of this stretch, since we were underbiking, and I needed my hands on the bars, rather than taking photos. We walked up the steepest, roughest portion of the first climb, and I spent much time out of the saddle on the coarsest gravel, which looked more like railroad ballast than the gravel used for building roads. (The above photo was taken on a smooth stretch where I could sit on the saddle and take my hands off the bars.)

Almost inevitably, we had a pinch flat. We were on the second gravel section, about five minutes away from 24 hours, so we continued on foot. Then our time was up (above), and we established our position. We had ridden 536 kilometers in the last 24 hours. We were tired and wet, but we felt a great sense of accomplishment. Everybody had been riding strong, and considering the rain and headwinds we had faced most of the way, we were very happy with our performance.

Then we took stock: We were 65 km from Olympia, and we were out of tubes for the tandem. We tried patching a tube in the rain, but even drying the tube with our last piece of clean clothing and then shielding it with a handlebar bag was not enough – the patch would not hold. Fortunately, Hahn’s 650B x 42 mm tires hadn’t suffered any flats, and we used one of his tubes to get the tandem moving again.

All that was left now was completing our ride to Olympia. Mark and I were starting to be hungry, so we pushed the pace a bit. I took the photo above without looking back. Only later did I realize that our friends were struggling a bit on this stretch. The upside was that we arrived in Olympia at 6:30, in perfect time for a shower and dinner, after 600 km on the road.

The next morning, we met the ten other Flèche teams for brunch. It was great to hear their stories, see the courses the other teams had charted, and reconnect with old friends, as well as make new ones.

Then we rode to the train station and took the train back to Seattle. It was a memorable, challenging ride, spent in the company of great friends – which is what the Flèche is supposed to be.

Further reading:

- More information about the Flèche Vélocio 24-hour ride.

- Blog entry from a previous Flèche ride.

- A report from the very first Flèche Vélocio in 1947. Bicycle Quarterly Vol. 3, No. 1, p. 24.