Gravel Myths (4): 700C Wheels Roll Faster?

Enve’s new MOG, launched last week, looks like a great bike. Riders report it’s exactly what a modern gravel bike should be. One thing that makes the MOG special: It’s designed for 700C wheels only. That means it’s simple, without flip chips and other gizmos to adjust the geometry for different wheel sizes. That’s also very much on-trend. These days, the vast majority of riders spec their gravel bikes with 700C wheels. Enve’s Jake Pantone explained: “After years of riding and evaluating 650B, it became clear that, like on the mountain bike, the one set up that was more confidence-inspiring and more fun than high-volume tires on a 650B rim, was high-volume tires in 700C.”

Many cyclists may be surprised that Jake didn’t say “…and faster.” Because that’s probably the main reason why 700C wheels have become so dominant. These days, if you read a ‘Guide to Gravel Tires,’ a bike test, or the marketing blurb for a new tire, it’ll probably talk about ‘fun’ 650B and ‘fast-rolling’ 700C wheels. Of course, we all want to go fast, so it makes sense to choose 700C wheels. You’ve probably read this so often that it comes as a surprise that there is no evidence that large wheels roll faster.

Careful testing has shown that large 700C wheels don’t roll faster than smaller 650B or even 26″ wheels, at least on the terrain that we cover on our gravel and all-road bikes: pavement, gravel, cobblestones… (We haven’t done any testing on mountain bikes, where other factors may be at play.)

Here at Rene Herse Cycles, we offer tires in all popular wheel sizes, so we really don’t care which wheel size people prefer to run. And we’re not trying to reverse a tend toward bigger wheels—there’s nothing wrong with riding on high-volume 700C tires. But we also know that not all riders are happiest on large wheels. In fact, there are good reasons to choose either large or small wheels. We’ll get to that later. Let’s first look at the science why large wheels don’t roll faster.

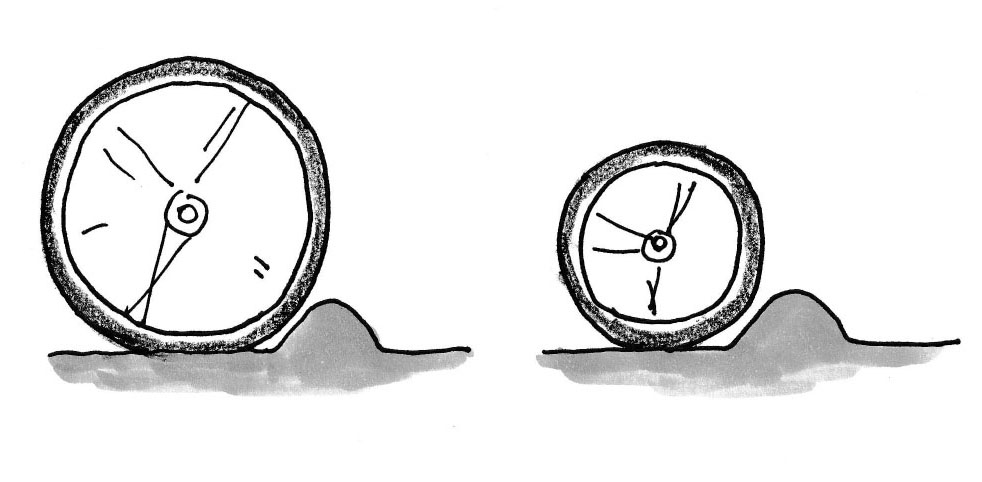

As with most gravel myths, at first sight, it seems like a no-brainer. For a bump of a given size, the larger wheel will have an easier time rolling over it. We can go into details of approach angle and so on, but the illustration above shows pretty clearly that a bump will be a greater obstacle to a small wheel than a large one. End of story?

If bicycle wheels were solid, that would be the end of the story (or this post). That’s why old stage coaches had huge wheels. The rear wheels were as tall as a horse—1.5 m (60″ inches”) or more. The front wheels had to swivel so the stage coach could go around corners: They were bit smaller, but still massive. The huge wheels reduced the resistance of pulling the stage coach over rough roads, and they made the ride a little more comfortable for the passengers inside. Back then, bigger wheels meant more speed and more comfort. That was more than a century ago…

Stage coaches aren’t really a thing any more, so let’s look at off-road race cars. They use relatively small rims. For example, the 2023 Audi etron for the Dakar Rally (above) runs 17″ wheels—less than a third the size of those old stage-coach wheels. The rims are small, but the tires are huge. What’s different from those old stage coaches is that the tires are filled with air.

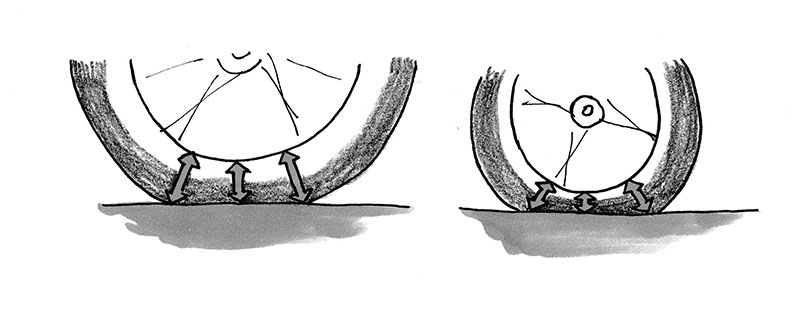

Pneumatic tires aren’t solid. And they don’t form perfect circles: They are flat at the bottom, because the tire flexes under the weight of the bike (or car). Small obstacles are absorbed by flex in the tire, not by lifting the entire bike over them. It no longer matters how easily the wheel can be lifted over the obstacles (as with the stage coaches), but how easily the tire can absorb them. Wheel size doesn’t really matter as long as the bumps are small enough that they can be absorbed by the tire.

This means that to roll fast over rough terrain, you don’t need large rims. Three factors determine the speed of your wheels on rough terrain:

- Wider tires, which can absorb bigger obstacles without lifting the bike.

- Supple casings, which require less energy to flex as the tire absorbs irregularities.

- Lower pressures, which allow the tire to absorb irregularities better.

To sum it up, the more obstacles are absorbed without lifting the bike, the less energy is lost. Which means more energy is available to move the bike forward.

Of course, anybody can post photos of stage coaches and desert racers, wave their arms, and make some theoretical arguments. That’s why we’re going to look at some real data next. In fact, this is the only scientific comparison of different wheel sizes in real-world settings that we know of.

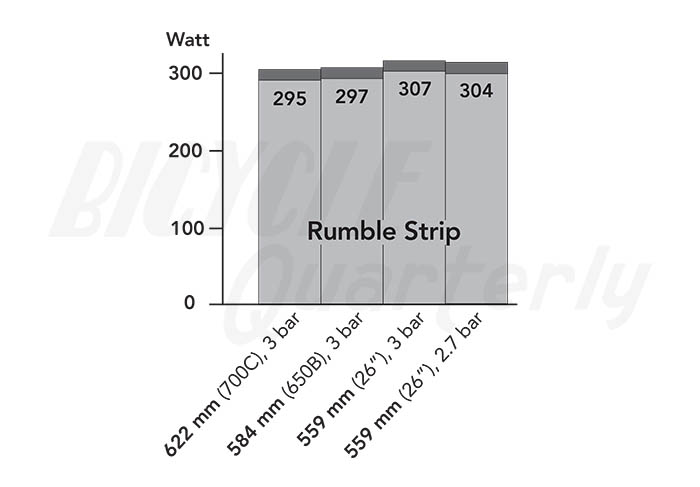

Years ago, we tested identical tires in three wheel sizes on rumble strips. Why rumble strips? Because they are more uniform than cobblestones or rough gravel. That means our tests are more repeatable—a key component of any scientific research.

If you’ve ever accidentally ridden onto rumble strips on a highway shoulder, you know how rough they are. Your entire bike turns into a blur. They are a worst-case scenario for rough road surfaces. If large wheels have an advantage, it would certainly show up here.

A few words about the methodology: We tested on a day with absolutely no wind and constant temperature. The rider kept the same position. (We independently confirmed in a wind tunnel that our test rider could adopt the same position time and again.) We tested at 5 a.m on a Sunday morning, so there was no traffic that might disturb the air. (The few times a car passed during a test run, we discarded the result and repeated the run.) We tested at 19.1 mph (30.7 km/h)—roughly the speed of top gravel racers. We repeated each test run three times, so we could do a statistical analysis of the results. Testing like this was hard work: After riding a total of 18 miles on these rumble strips, my body was as sore as if I had ridden Paris-Roubaix!

Above are the power measurements for each wheel size, plus the 26″ wheels with a slightly lower tire pressure that we ran as a check. (We wanted to see whether small differences in tire pressure have a significant effect on our results.)

I can hear some readers say: “But the 700C wheels were fastest!” Well, look at the dark gray ‘error bars.’ They overlap, meaning that the tiny differences between wheel sizes aren’t statistically significant. In other words, 700C wheels don’t require 2 watts (or 0.6%) less than 650B wheels… That’s just inevitable noise in the data, plus variations between individual tires. (Obviously, we had to test a different set of tires for each wheel size.)

The real conclusion from the data is this: The effect of wheel size on speed is too small to measure. Other factors are far more important. For example, when we ran different tire widths and different casings, we found much greater differences. (And they were statistically significant.)

Real-life experience confirms these tests: For my FKT (Fastest Known Time) in the Oregon Outback, I ran 26″ wheels. After traversing 364-mile (585 km) of rough gravel (and some pavement) in 26:13 hours, there was no doubt: My bike didn’t hold me back. All the previous FKT holders had ridden 700C wheels, and they were racers who were at least as strong as me. That doesn’t mean that bike and tire choice doesn’t matter. My ultra-wide 54 mm tires (and Extralight casings) probably contributed more to my speed than my fitness: The previous FKT holder ran 38 mm tires.

OK, so we know that large wheels don’t roll faster. What about the “more confidence-inspiring and more fun” that Enve’s Jake Pantone talked about? That really depends on your personal preferences. Here’s how it works: Wheel size has a large effect on a bike’s handling, because, all other things being equal, large wheels are heavier and thus generate higher gyroscopic forces. That means a big wheel is more stable. A small wheel is more nimble.

This affects how the bike corners. A bike with smaller and/or lighter wheels is easier to lean into a corner. A bike with bigger and/or heavier wheels is more stable, more reluctant to turn. Obviously, you want just the right amount of stability—a bike that neither is so unstable that it’s hard to corner on a constant radius, nor so stable that you have to force the bike into turns.

On gravel and other loose surfaces, the effect of larger or smaller wheels is not very noticeable. You simply can’t corner very hard before you lose grip, which means your steering inputs are small. (Above I’m at the limit on Odarumi Pass in Japan, turning the bars to the outside of the curve to catch a slide.) Having spent many miles on bikes in all three popular wheels sizes (700C, 650B and 26″), I can’t say that I notice huge differences between these different setups on gravel.

It’s a different matter on pavement, where you can lean the bike almost until your knee touches the road. When thinking about the best-handling bikes, I usually envision a bike with 700C x 30 mm tires. Not quite as quick-handling as a racing bike with narrow tires. But still agile enough that simply looking in the right direction makes the bike turn instinctively. I don’t like bikes that tend to run wide when I’m at the limit, or bikes that I have to push into the turn. To get the same handling with 42 mm tires, I need to down-size the wheels to 650B. And with 54 mm tires, 26″ gives me the same rotational inertia. So I naturally prefer those wheel sizes, especially since most ‘gravel’ rides include a fair bit of pavement. (These values are for aluminum rims. With carbon rims, the wheels are lighter, and the boundaries shift a bit.)

Every rider’s preferences are different. Natsuko has such a fine sense of balance that she prefers 30 mm tires on relatively small 26″ wheels. What feels a bit ‘twitchy’ to me is just ‘perfect and easy to steer’ for her. She’s probably an exception—many riders prefer a more stable bike, one that feels like it corners ‘on rails,’ where even tensing up and gripping the handlebars firmly won’t upset the bike’s course around a corner. What is ‘confidence-inspiring’ for some riders is ‘too difficult to turn’ for others.

When you ride out of the saddle and rock the bike from side to side, you also feel the gyroscopic forces of the wheels. I suspect that is the reason why racing bikes have been using 700C wheels for over a century, even though smaller wheels in theory would accelerate (slightly) faster. Wheels that are too small (and hence too light) may not give racers enough resistance to push against when rocking the bike. Wheels that are too big (too heavy) make rocking the bike difficult. That’s something you can easily feel when you ride a fatbike or a mountain bike with plus-sized 29″ wheels: You can move your body on top of the bike, but it’s virtually impossible to rock the bike itself in sync with your pedal strokes.

Again, preferences between riders vary. But if you’ve wondered why riding out of the saddle feels so different on a gravel bike with wide tires… that’s because the wheels are so much bigger (and heavier). If you prefer the feel of your racing bike, you don’t have to give that up just because you like wide tires—just run smaller wheels.

So when it comes to choosing your wheel size, don’t worry about speed. 700C, 650B and even 26″ all roll at the same speed, whether on pavement or gravel (and even the cobblestones of Paris-Roubaix). Instead think about the handling you want. Do you prefer a bike that’s nimble in corners like a racing bike? Or do you want your bike to corner ‘like on rails’? Also consider how you want to your bike to feel when you ride out of the saddle. In the end, choosing your wheel size is all about making your bike confidence-inspiring and fun—for the way you ride.

Photo credits: Andy Chasteen (Enve MOG); Audi (racecar); Mark Vande Kamp (rumble strips); Rugile Kaladyte (Oregon Outback)

Further Reading:

- Gravel Myths (1): Too much tire?

- Gravel Myths (2): Smaller Knobs Roll Faster?

- Gravel Myths (3): Wide Tires Need Wide Rims?

- Gravel Myths (5): Side Knobs for Cornering Traction?

- The 26″ Rene Herse bike for the Oregon Outback: Method or Madness?

- The full tests of suspension losses and different wheel sizes on rumble strips was published in BQ 29.

- Results of Bicycle Quarterly’s tire tests

- Our book The All-Road Bike Revolution explores how bicycles really work.