Half a Century Old and Still Going Strong

I am the fortunate custodian of a lovely 1962 Alex Singer that is in almost-new condition. It has all the features that make an Alex Singer special, and really represents Alex Singer’s ideal of the perfect bike: lightweight, elegant and performing.

Years ago, Ernest Csuka of Cycles Alex Singer sent the bicycle my way. I had wanted to order a new Singer with the same features. I remember him growling: “Those features are too difficult to make. I’ll have to find you an old one.” And he did!

The original owner ordered it for his retirement. He was a good customer, who already had bought several Singers. Orders were slow in 1962, and extra care was spent on this bike. All Singers from this period are very nice, but this one is nicer still. The original owner appears to have ridden it very little, so it rides like it did when it was new.

This year, the bike is a half-century old. To celebrate, I took it on a ride with my friend Sam.

Rolling along, this was the view of the bike. The bag is a special model made for Alex Singer by Sologne. (Today, it is made by Gilles Berthoud and available from Compass Bicycles.) Looking down put a smile on my face.

Both Sam and I had been working too many long hours, so we were especially eager to ride. Our pace was high, but the Singer had no trouble keeping up. Its handling was stable, yet agile. It responded well to my pedaling stroke, in the way the French call ‘nervous,’ a term borrowed from racehorses. I would translate it with ‘eager.’

The Nivex derailleur shifted as precisely as always, but I had to adjust my technique. Having ridden my 1970s bike with a more ‘modern’ derailleur lately, I had to stop ‘overshifting.’ With the Nivex, you move the lever until the new gear engages, and that is it. No fine-tuning necessary. The compensator lever on the spring keeps the chain tension constant, so every shift is exactly the same, no matter where you are in the gear range.

The front derailleur probably is the lightest ever made. Including the braze-ons, it weighs less than 50 grams. (An Ultegra front derailleur alone weighs 85 g, and then you have to add the cables, housing, shift lever…) It works remarkably well, even though the large step from the 32- to the 46-tooth chainring on this bike is not an easy shift. The compact gearing allowed me to ride in the big ring most of the time.

This bike is equipped with a chainrest. Next to the smallest cog, a ring is brazed onto the dropout. You can shift the chain onto the ring, and then remove the wheel without touching the chain.

Aren’t those Bell wingnuts lovely? They were forged for strength, so they never break or bend, even though they are made from superlight aluminum.

On a long downhill, I moved the chain to the chainrest. Now the chain no longer was on the freewheel, which allowed the freewheel to spin with the wheel. It was fun to coast in silence. Sam thought the reduced resistance made me go faster, but that is unlikely to be significant.

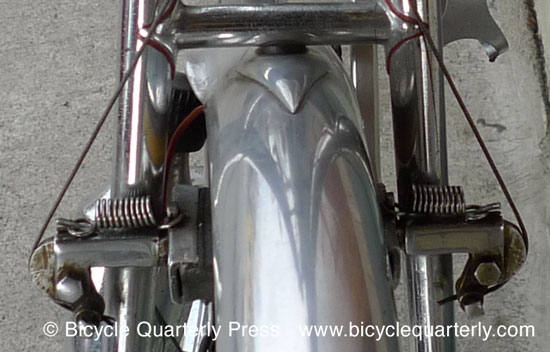

The Singer brakes are the lightest brakes I know, much lighter than modern Eebrakes and other minimalist designs. They work like this: Pulling on the cable rotates the cams, which push the pads toward the rim. There was plenty of brake power, but the brakes juddered terribly. I’ll need to file the pads to the correct toe-in again.

As we stopped at a cafe, I looked over the bike. I love the stickers on the Mephisto rims. The rims are superlight, and feature small wooden blocks inside the rim at every spoke hole to support the spoke tension.

I was grateful for the sealed bearings in Singer’s custom bottom bracket and in the Maxi-Car hubs. Neither have been overhauled – ever! – yet they still spin smoothly half a century after they were made.

Fortunately, we did not ride at night. The small light is cute, but it cannot compete with modern lights for illumination. Singer’s light mount is hollow, and the wire goes inside and then runs inside the rolled edge of the fender.

The taillight mounts to a dedicated braze-on under the chainstay. It’s well-protected there, and not blocked if you use a rear rack and carry a load. The frame is one of the most finely crafted I have seen regardless of maker or age; check out the connections of the stays to the dropouts.

The lugs have a fillet added to the crease to make them stronger and (more importantly) prettier. Roland Csuka, who brazed the frames, added a long tang to the seatlug. I suspect he welded the pump peg onto the lug before he brazed the frame. That prevented heating the seat tube again. The small cylinder on the seatstay is a lever control for the sidewall generator. You can see the ball end of the lever. You reach down to switch the lights on and off while moving. The fender has a neatly formed bulge to allow the generator to touch the tire.

Singer’s specialty was the unified head tube. Roland welded the lug sockets onto the head tube, before brazing the frame. The stem also is welded from steel tubing.

The saddle, a 1950s Brooks B17, is one of the most comfortable I have ridden. Its quality puts modern Brooks offerings to shame. Singers often had a seatpost with an internal expander, which gave a nice and clean look to the seatlug. You can see the expander bolt on top of the seatpin.

We rode 190 km that day, sprinting up hill after hill until we completely bonked. After we took a rest, we continued our manic ride. (It’s February, and rides like that help us get in shape for the season after losing much of our form over the winter.) The only allowance I made for the age of the bike was at stoplights. I accelerated a little more slowly to limit the torque on the rear wheel. There is no need to break half-century-old spokes!

Some may wonder whether such a pristine bike should be ridden at all, or whether it should be sealed away hermetically. I agree that it should not be allowed to deteriorate, but much of what makes such a bike special can be accessed only by riding it. Bikes like the 1962 Alex Singer have inspired Bicycle Quarterly’s vision of what a bike can be, both functionally and aesthetically.

P.S.: This 1962 Alex Singer is featured in our book The Golden Age of Handbuilt Bicycles, where you will find studio photos of this and 49 other special machines.

P.P.S.: Several people asked about the rear brake cable routing. Here it is (click on the photo for a bigger image):