Helmets Wars – Missing the Point

Update 8/2024: This post was written in 2014. Fortunately, since then, the discussion about helmets has moved on, and ‘helmet wars’ seem to be a thing of the past. Below are the reasons why it makes sense to wear a helmet yourself, but it does not make sense to insist that others wear helmets.

In the U.S., most ‘responsible’ cyclists wear helmets, yet when I cycle in Europe or Japan, I see many cyclotourists who ride without helmets. The Europeans or Japanese don’t seem like dare-devils or poorly informed. What is going on here? I’ve thought about this a lot, and I’ve concluded that helmets don’t matter all that much, compared to other factors that that influence the safety of cycling.

Please note that I am not anti-helmet. When I was in college in Germany, I was one of two cyclists in town who wore a helmet. I’ve worn a helmet on most rides since then. Even so, I have revised my views on this topic – while continuing to wear a helmet.

As an individual cyclist, safety comes from being able to control your bike and from being able to anticipate traffic’s often erroneous moves. On a societal level, safety comes from having so many cyclists on the road that cycling is normal and accepted.

A helmet is only the last line of defense when everything else fails.

What about the arguments in the “helmet wars”? Let’s look at them one by one:

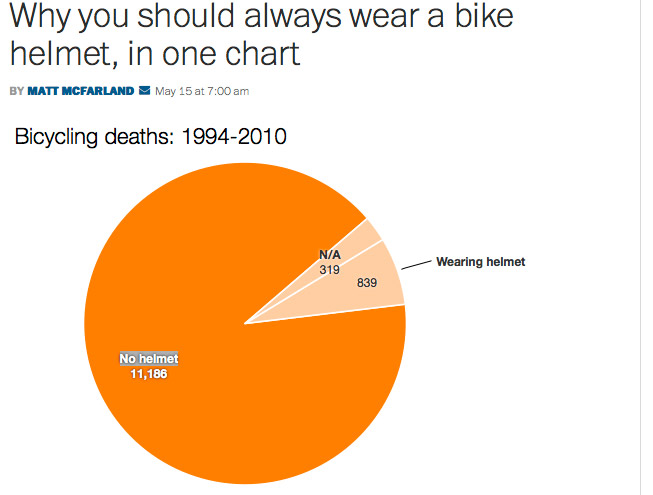

1. Most cyclists who died didn’t wear helmets (used as proof that helmets save lives).

This analysis assumes that riders who wear helmets and those who don’t wear helmets otherwise behave identically. They don’t.

Consider that 25% of cycling fatalities occur between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. Most people who are getting killed aren’t randonneurs on night-time rides. They were people who lost their driver’s license because of drunk driving. (31% of cycling fatalities have blood alcohol levels of 0.08 or higher.) These fatalities were on their way home from the bar. Most of them don’t wear helmets, but they also are riding a bicycle while intoxicated, without lights, usually on busy highways, just after the bars close. The lack of helmets is their smallest problem.

To figure out how effective helmets really are, you’d need a randomized trial, where you assign riders randomly to wear helmets or not each day they ride. The riders shouldn’t know whether they are wearing a helmet, so you’d give the “no-helmet” riders a placebo – something that looks like a helmet, but doesn’t protect your head. Of course, you wouldn’t do a trial where you potentially put riders in harm’s way, so this is a non-starter.

So these statistics can be misleading. The good news for us is that the statistics also overestimate the dangers of cycling. If you do not ride drunk, without lights, after midnight, on busy highways, then you already have reduced your accident risk significantly.

A better way is to compare statistics from one country to the next. And there, we find little evidence that the countries where people wear helmets (like Sweden) see fewer cycling head injuries than those where people don’t wear helmets (like Denmark).

Conclusion: Helmet use doesn’t seem to have a great impact on overall cyclist fatality rates.

2. Helmets make cycling appear more dangerous than it is.

In the U.S., when I part with people and get on my bike, many say: “Be safe!” or “Be careful out there!” I don’t get that in France, where people encourage me with “Pedalez bien!” (Ride well!)

When I drive a car or walk, nobody says “Be safe!” Modern cars are equipped with airbags, so you don’t have a wear a helmet while driving. It would be cheaper and safer to wear helmets – race cars don’t have airbags, yet are much safer than the cars we drive on the road. But helmets would reinforce the message that you are about to engage in a dangerous activity, whereas airbags are invisible until you need them…

In reality, cycling becomes safer if more people ride. Cycling in Copenhagen is relatively safe not because the cyclists there are more skilled. Nor do the cyclepaths reduce the risk of accidents (they don’t). Cycling in Copenhagen is safe because everybody is used to looking for cyclists.

Furthermore, if everybody cycles, drivers no longer harbor resentments against cyclists for their presumed political views and social preferences. In the U.S., much of the animosity against cyclists stems from what people perceive cyclists to stand for – city dwellers, liberals, granola-crunchers – rather than from the minor inconvenience they may cause on the road.

Conclusion: Emphasizing helmets discourages people from cycling, which makes cycling less safe.

3. Helmets provide a false sense of security, therefore people feel they can take more risks.

The initial argument for risk compensation was based on the fact that more cyclists die in countries where riders wear helmets (U.S., UK) than in countries where cyclists ride bare-headed (Europe). The conclusion was that helmets somehow make cycling less safe, and the best hypothesis seemed to be that riders who wear helmets feel invulnerable and take greater risks (risk compensation).

The data do not support this analysis. In the U.S., most riders who die don’t wear helmets (see 1), so the higher death rate in the U.S. cannot be explained by risk compensation of helmet-wearers. In fact, helmets take the “carefree” out of cycling and make people more aware of the risks (see 2.).

There is a concern about helmets, though: If we tell new cyclists that a helmet is all they need to guarantee their safety, we are putting them in harm’s way. Real safety comes from accident avoidance through looking ahead, anticipating others’ behavior, and judging the road conditions correctly.

We see the same in cars, where we North Americans focus on buying big cars with the best safety ratings, but not on learning to drive well. And our traffic fatalities are among the highest in the industrialized world, much higher than in countries where people drive small (and relatively unsafe) cars with greater skill. (By the way, I’m not taking any risks in the photo above: I’m riding well within my capabilities and those of the bike and tires.)

Conclusion: As a society, a focus on helmets detracts from teaching about real safety.

So where does all that leave us? From my perspective, there are two conclusions:

- On an individual level, wearing a helmet is a good idea. It is likely to reduce your injuries in many crashes, and it rarely seems to do any harm. The “rotational brain injuries” often quoted by helmet opponents seem to be very, very rare. (I hit my head and cracked my helmet in a recent accident, and fortunately did not sustain a head injury. I ‘only’ broke my hand.)

- On a societal level, insisting on helmets is detrimental. It detracts from the facts that a) cycling is relatively safe, and b) that real safety comes from preventing accidents more than from trying to survive them.

Wear a helmet if you are an ‘optimizer’ – the type who worries about the last 5% in performance or safety. (I do wear a helmet!) But don’t tell anybody else to wear one, or not to wear one! Instead, let’s focus on teaching cycling and traffic skills. Will this analysis end the ‘helmet wars’? I am not holding my breath…