Innovations of the last 25 Years

It’s almost 2025! A quarter century has passed since that big landmark, the year 2000. It’s a great moment to take stock of the revolutionary changes in cycling over those 25 years, and then have a look how things might develop in the future.

Natsuko and I talked about the things that have shaped cycling in the last quarter century. Not small things like adding a few cogs to rear cassettes. We were looking for big changes that have revolutionized not just bikes, but also cycling culture—in good and sometimes not-so-good ways. The following are the top dozen on our totally subjective list. Interestingly, none of them were ‘invented’ this century, but they all made their impact during the last 25 years.

1 Wide tires: Changing not just our bikes, but also where and how we ride.

In 2000, I (Jan) raced on 21.5 mm tubulars. So did all the other top-level racers around me. We ran our tires at 9 bar (130 psi) or more. If our pressure dropped below 100 psi, it meant we had a flat.

Today, even Tour de France champions like Tadej Pogačar roll on 30 mm tires at 4 bar (58 psi)—twice the air volume and less than half the pressure we were running back then.

Wide tires haven’t just made bikes more comfortable and faster. They’ve also changed where and how we ride. In the past, we often preferred busy, straight highways, because the asphalt was smoother there. Now we ride on winding backroads with no traffic, and our tires absorb the rough asphalt—and occasional gravel—without us gritting our teeth. Wide tires have brought more speed, more comfort, fewer flats—more fun. A true revolution.

2 Gravel: A new dimension of cycling

Riding on gravel was almost unknown in 2000. The few gravel events that existed usually carried ‘Roubaix’ in their names—they used gravel as a stand-in for cobblestones that are rare in the U.S. Gravel has changed cycling like mountain biking did 20 years earlier—or perhaps even more. Gravel bikes have replaced road bikes as the default for riders interested in cycling as a sport. This can only be a good thing, as wide tires are great for all surfaces, not just gravel. And it’s fair to say that road bikes probably wouldn’t have moved to 30+ mm tires without gravel showing the way.

Riding on gravel has added a fun perspective to road cycling. It’s not just the lack of traffic and beautiful scenery, but also the completely different feel when our tires have less grip on the surface.

3 Bikepacking: Take any bike on a tour

If we wanted go on a self-supported bike tour in 2000, we first needed to equip our bike with racks. Ideally, we’d get a purpose-built touring bike. That was a big barrier for most riders. Trailers were the first iteration of the idea to take any bike on a camping trip, but the ‘tail-wagging-the-dog’ feel made trailers a blind alley.

Bikepacking distributes our (lightweight) gear over multiple pieces of luggage that are strapped onto the bike frame itself rather than separate racks. No longer do we need a special bike. Bikepacking has democratized touring, and it has enabled us to explore remote places where panniers are impractical. Heading out for a cycling adventure has never been easier, and many cyclists are heeding the call.

4 GPS: Knowing where we are

In 2000, if we were exploring new terrain, we carried a paper map. Today, our phones can pin-point our location even when there is no cell reception.

This has changed cycling far beyond how we navigate on the road. GPS tracks have made it easy to share routes. In 2000, the first thing we did after moving to a new place was join a cycling club to find out where to ride. Now we go online. In 2000, if we wanted to see how our speed stacked up against other riders, we joined one of the fast-paced weekend group rides that existed in every town. Today, we try for a Strava KOM. And Zwift gives us the option of riding and even racing without ever heading outside.

All this has also made cycling into a more solitary pursuit at the expense of the friendships that we used to form on the road. Fortunately, GPS doesn’t keep us from joining groups and riding with friends. We just have to seek them out more consciously.

5 Smartphones: Having a camera on every ride

In 2000, it was rare to bring a camera on our rides. And even if we did, operating it required considerable skill. Ride reports were made up mostly of words, rarely shared beyond a small group of friends or club members. Today’s rides are shared on Instagram and other social media platforms in beautiful photos. As much as we value long-form writing, cycling is all the better for the visual inspiration that’s shared so widely.

6 Modern lighting: Making night rides fun

When I rode my first Paris-Brest-Paris in 1999, I equipped my bike with a sidewall generator and a halogen headlight. These parts were developed for German commuter bikes. The headlight bracket failed after 800 km (500 miles), unable to withstand the vibrations of riding at speed. For other brevets, I used a Nightsun light with a rechargeable battery that filled an entire water bottle and still held only 5 hours of charge. A few years earlier, the first modern generator hub had been introduced by Wilfried Schmidt in Germany, but it was still far outside the mainstream.

Whether it’s our Edelux II LED headlights or inexpensive rechargeable strap-on lights, riding at night today is much better and safer. The best lights allow us to ride at night with the same speed, safety and fun as during the day—even on gravel. Unsupported ultra events like the Tour Divide, the Silk Road Mountain Race and Unbound XL wouldn’t be the same without modern lights.

7 Discs: Powerful brakes at (almost) every price point

With discs, brakes no longer need to reach around the tires. That has freed up bike design and allowed wider tires at every price point: Inexpensive disc brakes work much better than inexpensive rim brakes for wide tires. That’s a huge change.

There’s still a place for rim brakes in specialized applications. Rim brakes are lighter, often offer better feedback, and allow for flexible fork blades that can provide suspension. That’s why many of our bikes run rim brakes, and we offer both cantis and centerpulls in the Rene Herse program. But for mainstream bikes, discs have made wide tires safe and fun.

8 Rando Bikes: The sportscars of bicycles

In 1999, Mark and I each spec’d our ‘forever’ bikes and had them custom-built. Even though we didn’t know each other at the time, our bikes were similar: They distilled the state of the art 25 years ago. Versatility was key—the ability to swap between narrow and wide tires, to add and remove racks and fenders, to mount lights and take them off again. Sturdy frames allowed for all these options. A ‘neutral’ mid-trail geometry that was intended to triangulate between nimble road bikes and stable touring bikes. Both Mark and my 1999 ‘dream bikes’ still exist, but they haven’t been ridden in years.

The discovery of fully integrated rando bikes—their light weight, performance, reliability and elegance—has revolutionized how we ride. We now carry our luggage on the front, so we can rise out of the saddle without changing the bike’s feel. Our bikes have geometries designed to be stable, yet nimble, with these loads and the wide tires that we run all the time. Fenders, racks and lights are integrated parts of our bikes. We suddenly realized that even top-tier sportscars come with permanently mounted lights and fenders (plus space for a little luggage). There’s no reason why our bikes shouldn’t use the same philosophy.

If somebody had told me in 2000 that Peter Weigle would build a modern, no-compromise bike for the Concours de Machines (above) that weighs just 20 lb (9.1 kg) with rack, fenders, lights, bottle cages—even the pump—I would have laughed. Now even the bike I ride in Unbound XL weighs just 12% more, despite running 54 mm tires and being sturdy enough to be ridden over the roughest gravel roads—again and again.

9 Tubeless tires: Eliminating the fear of flats

With no tube to pinch, tubeless tires have eliminated the biggest worry of riding on rough terrain. Tubeless tires are essential for gravel bikes—unless we run ultra-wide tires that rarely bottom out. (Tubeless is even more essential for mountain bikes, but they aren’t covered here.) Just as importantly, tubeless sealant has eliminated most flats on pavement—a huge benefit when we ride on shoulders of busy highways that are littered with debris. (As are the bike lanes in many cities.) The downside has been the sometimes difficult setup (especially on sub-optimal rims) and the upkeep, with sealant needing to be replenished frequently.

Tubeless technology has also forced tire and rim makers to improve their standards. Today, rim and tire fit is far better than it was in the past. Unfortunately, that has also made modern tires much harder to mount on classic road rims—Mavic MA-2 and similar—that had very shallow rim beds.

For a while, tubeless technology was promoted as a panacea for everybody. Today we have a more nuanced view. Most of us agree that tubeless tires are useful for many riders, but tubes have made a strong comeback. They are still the best option for riders who don’t get many flats to begin with, and who don’t want to worry whether their sealant has dried out. And the new TPU tubes are faster and stronger than the butyl tubes we ran in 2000.

10 Electronic Shifting: Completing the digital revolution

In 2000, mainstream bicycles already used shifters that were integrated into the brake levers: Shimano’s STI, Campagnolo’s Ergopower and SRAM’s DoubleTap. Mechanical shifting meant that faults were easy to diagnose—even if the shifters themselves often were not repairable. However, mechanical brifters could be difficult to operate, especially for riders with small hands. Front derailleurs could not be trimmed, so they rubbed on the chain in certain gears. Tiny ratchets inside the levers wore off within a year or two if we shifted too fast. Fraying cables were hard to detect, and once they broke, they were hard to fix, requiring removal of the handlebar tape.

Electronic shifting takes the skill out of shifting, for the better (no more worn ratchets, no more clacking noises if we didn’t push the lever far enough) and worse. The change runs deeper than that. Bicycles used to be simple machines where each component was easy to understand: A lever pulls a cable, which moves a derailleur, brake caliper, etc. Today’s components are like smartphones: black boxes that operate at the push of a button. How they work is hidden from view. (Disc brakes play into this as well.) With this digital transformation comes less emphasis on repairability. Will we be able to get replacement batteries for today’s electronic shifters in 25 years?

Fortunately, for those of us who like to be involved in the workings of our bikes and miss analog cycling, there are alternatives. New custom bikes can be spec’d with the desmodromic Nivex derailleurs. Or we can source used parts and mix-and-match them in creative ways.

11 Wool Clothing—keeping us comfortable no matter the conditions

For my own riding, the revolution in clothing has been just as important as the bikes themselves. I recall a 1990s autumn tour across Snoqualmie Pass. Wearing the latest ‘technical’ performance fabrics, I got sweaty on the uphill, then chilled on the downhill. When light rain started, I became borderline hypothermic.

Merino wool jerseys and tights have changed how I ride at this time of year. No longer scratchy and stiff, the best wool clothing adapts to a wide range of temperatures and continues to insulate even when wet. Where other riders stop on tops of mountains to add layers, only to remove them after the descent, I can focus on the ride and continue without delay. Wool not retaining odors is another benefit on multi-day adventures. However, mainstream makers’ attempts to mix wool with synthetics have often failed to capture the advantages of either. For wool clothing to really offer the promised benefits, it needs to use the best Merino wool, and little else.

12 Rapha: Making cycling cool again

In 2000, high-end cycling jerseys were garish, with huge lizards or other emblems plastered across them. Inexpensive jerseys were simpler, but the colors were chosen without any consideration to aesthetics. A stylish cyclist seemed like an oxymoron. It got so bad that I took matters in my own hands, designing a simple blue jersey for the Seattle Randonneurs based on a design I had seen on two older riders in Paris-Brest-Paris. That jersey design was so unusual that our club became known as the ‘blue shirts.’

Then came Rapha. Many of us raised our eyebrows at sky-high prices and early products clearly designed by non-cyclists—like socks reinforced where the leg might touch the chain. But Rapha brought new energy to the cycling world. Where most cycling products were copies of existing ideas, Rapha created something new: stylish cycling clothing and stories to go with them. With a few exceptions, the function and design of the clothes quickly caught up with the marketing. Rapha’s impact was so profound that it went beyond clothing: Colors and logos on frames, rims and other components from other makers became more understated, too. As Rapha took the cycling world by storm, cyclists started to look good—even to non-cyclists. Cycling became cool again. And we’ve all benefited from that.

The Future

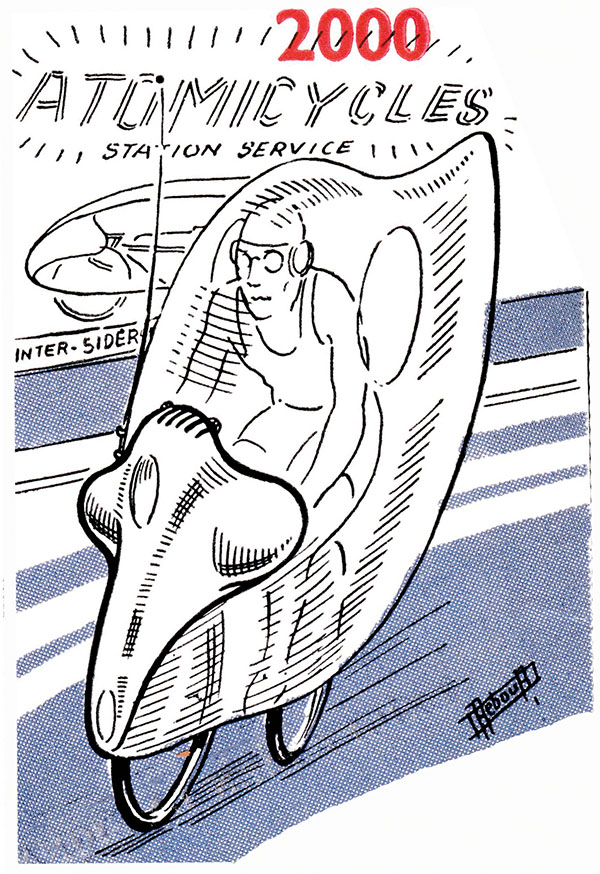

In 2000, many thought the future of cycling looked a lot like Daniel Rebour’s prediction from half a century earlier: Faired recumbents and nanotechnology seemed just around the corner. Beyond that, cycling’s future seemed bleak 25 years ago. During the 1980s and 90s, tires had become narrower, and road bikes had become the only bikes that mainstream makers were promoting. Many racing bikes were designed to fit only 20 mm tires. If somebody had predicted that, 25 years in the future, Tour de France winners would ride 30 mm tires on smooth roads, they would have been laughed out of the room.

Today road bikes as we knew them in 2000 have become extinct, and so have 20 mm tires. Even bikes built purely for speed have tires wider than those of loaded touring bikes 25 years ago. Attitudes about cycling have fundamentally changed together with the bikes. There is much more diversity than there was in 2000: of riding styles, of bikes, of genders, of body shapes…

Cycling used to be a sport where everybody seemed to always be training for their first century. Now it is an activity that can be enjoyed in many different ways. The old hierarchy that placed racing above touring, long rides above short ones, naked bikes above fully equipped ones, has been upended. Today, all types of riding have equal value. That, more than the technical details of the bikes, is the real change of the last quarter century, and it provides context for predicting the future.

Where are we headed from here? After the radical changes of the last 25 years, it seems likely that the next 25 will be spent consolidating those gains. Wide tires and gravel bikes are here to stay. Their advantages are too obvious to fall by the wayside. That won’t keep the bike industry from promoting new trends to persuade us that we need new bikes. Instead of revolutionary changes, detail improvements are likely.

Gravel bikes will probably continue to move to wider tires until they reach 55 or perhaps even 60 mm. Any wider, and the tires won’t fit between low-Q cranks that facilitate a powerful spin. Even wider tires would also run at pressures so low that they’d pogo like early full-suspension mountain bikes.

Our studies of suspension losses suggest that front suspension of some sort could make gravel bikes faster. MTB-style telescopic shocks have been tried and rejected on gravel bikes, but undamped flex like the Lauf fork or small-diameter steel fork blades hold a lot of promise.

Road bike tires may already have reached their limit. It’s hard to see what pros like Pogačar would gain from going wider than 30 or 32 mm. For the rest of us, 38 or 42 mm is plenty for riding on paved roads.

Fenders and lights have become more widespread, and their integration into production bikes will (hopefully) continue to improve. Aerodynamics will probably move beyond the current focus on wheels with deep rims—which offer limited benefits with wide tires. Other areas offer more potential for improving aerodynamics—witness the recent trend toward narrower handlebars. Perhaps more attention will be paid to the ergonomics of handlebars, since gravel races go over longer distances and rougher terrain than traditional road races.

Anti-lock brakes may be the next step in the digitization of bicycles, as it’s been in cars and motorbikes. (Rather than modulate the brakes yourself, simply pull the lever, and electronics do the rest.) Hopefully, this will be combined with a new disc brake standard that finally stops the calipers from moving out of alignment from the vibrations of hard braking. Automatic shifting seems less likely to migrate from cars and motorbikes to bicycles, but it’s probably safe to predict that makers will add a few more cogs to their cassettes.

None of these changes are revolutionary—more like fine-tuning around the edges. Perhaps after two-and-a-half decades of groundbreaking developments, bicycles are once again becoming mature technology. That would benefit us as riders—shifting the focus to perfecting small things that were overlooked in the rush to adopt new materials, new technologies and new riding styles.

But who knows? In 2000, nobody—certainly not us—saw the ‘wide-tire revolution’ coming. It’s possible that a similar scientific breakthrough will allow cycling to make another quantum leap in the next 25 years. Let’s hope so—and let’s also make sure we’ll distinguish between real improvements and simple fads as we evaluate the developments of the next quarter century.