Jan sets Oregon Outback FKT

Few rides have captured my imagination like the Oregon Outback. It’s not just the epic scale of it – traversing the entire state of Oregon on gravel roads – but also the varied landscapes. I love the wide-open sagebrush country in the south. There are few better roads than the steep and twisty ribbons of gravel that traverse the Ochoco Mountains. At the end, the incredible descent into the deep gorge of the Columbia River is something you’ll never forget. Overlaid on top of that are the challenging riding conditions: The gravel of eastern Oregon is rough and loose.

In fact, that makes this ride a perfect test for all-road bikes. The Oregon Outback has been hugely influential on bike technology. When the event was first mooted in 2014, gravel bikes still had 28 mm tires! I showed up at the start on 42s, confident that my bike could handle everything the Outback could throw at it. I quickly realized that wider tires would be better. The result were our 650B x 48 Switchback Hills and 700C x 55 Antelope Hills, named after climbs on the Outback course. These days, road bikes have wider tires than the gravel bikes of 2014!

Ever since that first ride over the Oregon Outback, I’ve been dreaming about building the ultimate all-road bike – a road bike that can handle the rough gravel of eastern Oregon. Now that dream bike is a reality, with a frame by Mark Nobilette, paint by Peter Weigle, and a lot of parts from Rene Herse Cycles – most already available, some still in the prototype stage.

It was only natural to head out on the Outback course again to see whether our ideas really work in practice. Is the all-road bike really as revolutionary as we think? So this wasn’t just a ride, but also a proof-of-concept of an idea: Can an all-road bike traverse the very rough and loose gravel of the Outback at road bike speeds and with road bike fun?

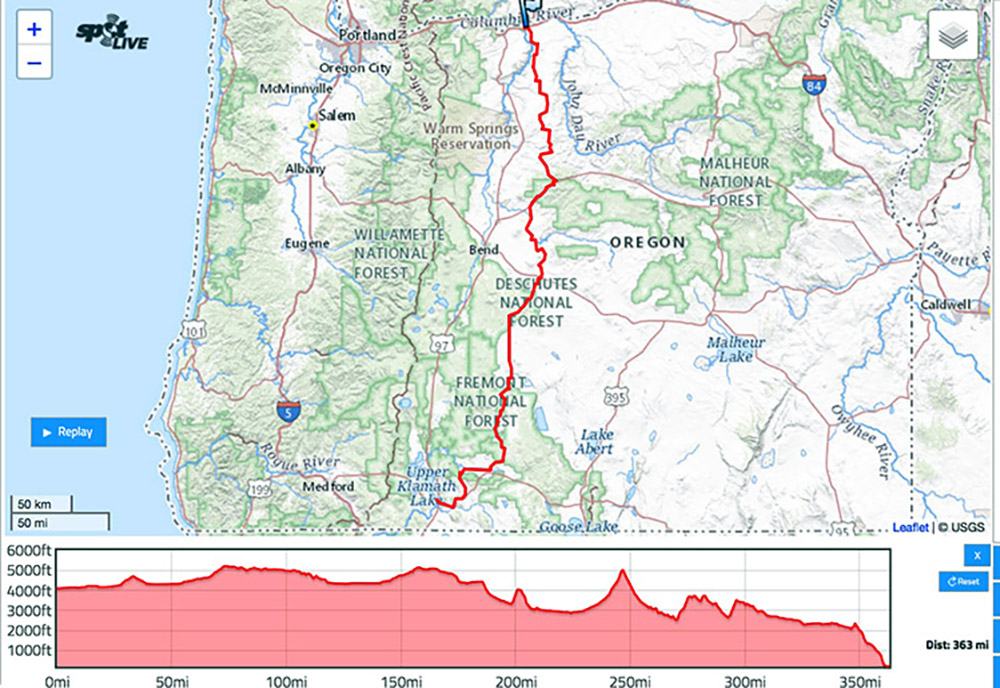

The benchmark was the FKT – Fastest Known Time – set by Steve Hartzel, one of Portland’s top cyclocross racers. Last year, he rode the course in 27:27 hours.

The bike is only one part of the preparation. The Oregon Outback course is very remote, with only a few places where resupplies are possible. For sub-40 hour rides, I’ve found it most efficient to carry everything I need, and only buy water and other liquids along the way. All my supplies fit in my handlebar bag. (A future article will discuss the things I carried.)

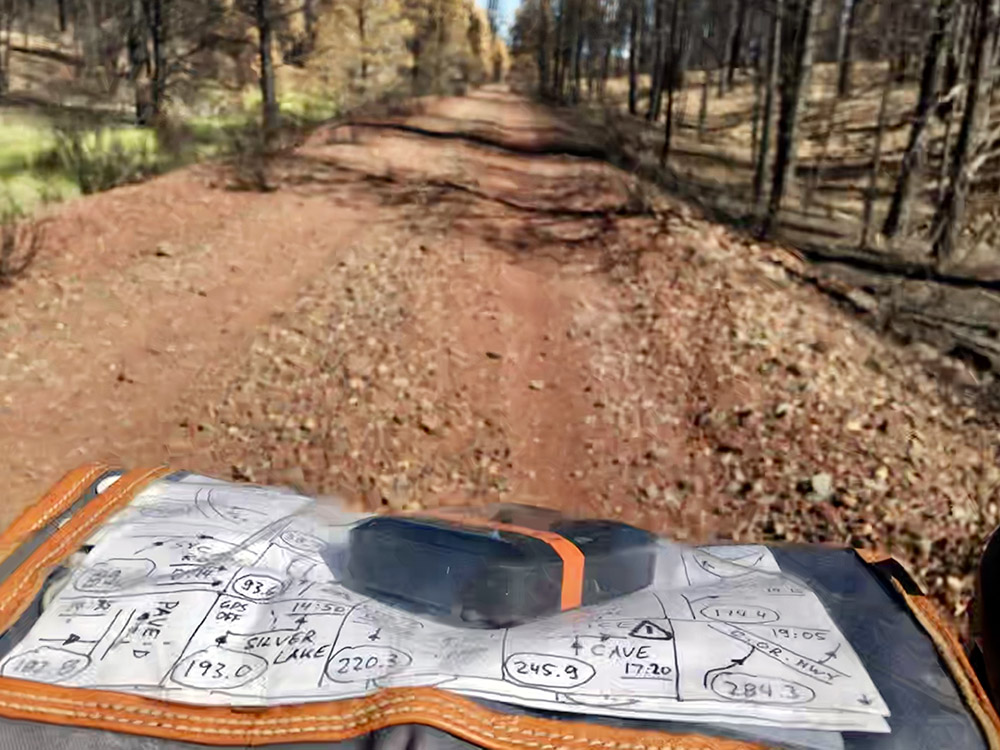

Making a detailed route sheet not only acts as a fail-safe in case the electronics don’t do their job – the Oregon Outback is infamous for GPS problems – it also helps me visualize the course. I love rides where the entire distance fits on two sheets of paper!

And then it was time to take the train to Oregon. I brought only the things I’d carry with me on the ride, plus some old clothes that I’d discard at the start of the ride. Unsupported in this case really meant that I was on my own…

On Tuesday morning at 6:30, I left the start point of the Outback route, the Maverick Motel in Klamath Falls. For 27 hours, give or take, I’d be pedaling as fast as possible and stop as little as possible. I enjoy the single-minded focus of efforts like this. Compared to the many challenges of daily life, it’s simple. A rare luxury to focus on one thing only, and do it as well as possible: Pedal the bike.

The hardest part during the early hours of a big solo ride is to settle into the right pace. Too fast, and you’ll bonk and lose time. Too slow, and you also lose time that you can’t make up. I find that I just listen to my body and do what feels comfortable.

And I enjoyed the scenery. The sun rose in a gap in the hills as the trail was heading toward it. It was amazingly beautiful. (Some people say that the endorphins of working hard make the scenery look twice as stunning.)

During an FKT attempt, there’s no time for photography. Still, on one of the smoother sections of the trail, I couldn’t resist, so I pulled out my cell phone. This was about where I entered the forest fire zone.

Forest fires are interesting in what they burn and what remains. The meadows were still green, yet the fire was clearly big enough to jump across the trail. Some trees were relatively unscathed, and even some of the charred trees might grow back. The paint of the sign just past one of the many cattle gates had bubbled. This had been a big fire: I rode for hours through charred trees.

Eastern Oregon seemed deserted this time. The only traffic I saw were park service trucks keeping watch for fires. The roads were in much-worse condition than I’d ever seen them: giant washboard ripples, deep ruts, or ultra-loose gravel. My all-road bike handled most of these without slowing down much.

The trail is getting very overgrown in places. I used narrow handlebars for aerodynamics, but they also helped weave through the vegetation that is springing up in the middle of the trail. In the fire zone, my legs got black from charcoal as they brushed against the burnt brush.

Keeping stops short is essential for a fast time. I had planned two stops – Silver Lake and Prineville are conveniently located at the 1/3 and 2/3 distance. It was a hot day, so I made an unscheduled stop at a tavern in Fort Rock. Total time off the bike was about 26 minutes:

• Silver Lake (km 193): 8 minutes (water, ice cream)

• Fort Rock (km 220): 3 minutes (water, Coca-Cola)

• Prineville (km 363): 15 minutes (water, Coca-Cola, apple juice, chips)

Pedaling hard – there’s hardly any coasting on the first 2/3 of the course, the day passed quickly. The almost-full moon rose spectacularly as I descended into the Crooked River Canyon. I’d seen the light behind the horizon, and then the giant pale yellow disc emerged above the hillcrest. Riding long distances allows me to experience sights that are out of the ordinary. It’s really special.

By the time I reached Prineville at km 363, I was ahead of schedule. The hardest (and most fun) part of the course was to follow – the Ochoco Mountains. Having pushed hard during the early stages of the ride, the climbs seemed longer than I remembered them, but bike and body continued to work in unison. The descents were fun, and all but one of the river crossing were dry. My 54 mm-wide tires handled the big cobbles without slowing down, and even the watery crossing only got my feet slightly wet.

By the time the sun rose for the second time on this ride, I’d already climbed Antelope Hill. As the morning sun tinted Wy’east (Mount Hood, above) and Klickitat (Mount Adams) pink, I was speeding along gravel farm roads that head to the Columbia River. Almost there!

What looks like a gradual downhill for the last 100 km on the course profile is actually a series of steep rollers. The farm roads dive into small valleys and climb sharp ridges. With the finish approaching, I wanted to speed up, but there was nothing left: I had judged my effort well.

With my last forces, I climbed Gordon Ridge and let the bike fly on the final descent toward the Columbia River. The wind whistled past my face, my tires were barely touching the ground – it was a final crescendo that required total focus. A fitting end to an epic ride!

The mad rush ended suddenly on the Columbia River. In 30 minutes, I had descended 670 m (2200 ft). A mile or so into a headwind was all that remained. And then there was the Deschutes River Park. Knowing that it can take a few minutes until the tracker updates (even if you force it), I took a quick photo of my watch. I had worked this hard and wasn’t going to give up even a minute of my hard-earned effort!

26:13 hours is more than a hour ahead of my schedule (and of the previous FKT). It’s also almost four hours (!) faster than my time in the inaugural Oregon Outback in 2014. In fact, even on a paved course, 585 km would take me almost that long. It seems that the all-road bike is working. And fortunately, there had been no bike trouble at all: Apart from the dry and squeaking chain, my new bike is none the worse for wear.

The biggest surprise of the entire ride happened a few minutes later. A car pulled up and somebody who looked vaguely familiar shouted “Congratulations!” out of the window. It was Mark, my training partner from years ago, when we both raced on the University of Washington team! He’d seen my posts, and since he lives nearby, he came to say ‘Hi.’ It was a fun reunion, and, even better, he offered to drive me to the train station in Portland. I have to admit I wasn’t looking forward to 100 miles of riding into a headwind! Instead we spent a nice couple of hours catching up, and we decided to ride together again soon.

With any record on a novel bike, you wonder how much is the rider and how much the bike. I can’t really claim to be hours faster than the stellar athletes who’ve ‘done a time’ on the Oregon Outback, so the bike plays a big role. Certainly, the combination of ultra-wide Extralight tires (I ran 26″ x 2.3″ Rat Trap Pass) with a road bike ergonomics (riding position, narrow Q factor, super-comfortable handlebars) made the Oregon Outback not just go by faster, but also much more fun.

More Information:

- Full story of the FKT ride is in Bicycle Quarterly 78.

- Jan’s bike and the story of Jan and Lael’s earlier ride across the Oregon Outback are in Bicycle Quarterly 77 (above).

- Full track of the Oregon Outback FKT.

Photo credits: Rugile Kaladyte (top photo; taken in Spring 2021); Mark Ahrens (finish line photos)