On the Ragged Edge: Tahuya 600 km

Twenty-twenty-three is a PBP year. Cyclists who want to participate in the world’s oldest long-distance event also ride four brevets to qualify: 200, 300, 400 and 600 km. (Paris-Brest-Paris is organized every four years.) The idea is that riders build their stamina, speed and experience until they are ready for the big 1200-km (765-mile) ride from Paris to Brest and back. This is not just good preparation—it also brings a welcome focus to the cycling season. Ready or not, we’re riding long distances!

That’s the theory, at least. Now it’s Friday afternoon, and my rando bike isn’t ready. I’ve used it to test some prototype parts, and taken them off for evaluation. Now the bike is in pieces, far from ready for tomorrow’s 600 km (375 mile) ride. As I assess the time I’ll need to work on the bike, I look at my Oregon Outback Rene Herse. I haven’t ridden it since last autumn, but it’s ready to go. With its narrow 40 cm handlebars and aero ‘fenders,’ it’s at least as fast as my PBP bike. With its 54 mm tires (instead of 42s on the PBP bike), it should be even more comfortable.

Taking a bike with 54 mm on a long-distance ride that’s on pavement almost exclusively? Funny how that no longer seems like an odd choice. We’ve seen so many times that 54 mm tires don’t roll slower than 42s, or 25s, for that matter—provided all tires feature the same supple casings. I inflate the Rat Trap Pass Extralights to ‘road’ pressure—all of 2.1 bar (30 psi)—check the alignment of the brake pads, and take the bike for a spin around the neighborhood. Even after its ‘hibernation,’ everything works just as it did last autumn. The bike feels wonderful on Seattle’s bumpy asphalt. I’m reminded how much I love this bike. Tomorrow will be great.

The next morning, more than 60 riders are at the start just south of downtown Seattle. It is nice to say Hi to old friends and meet new faces. Randonneuring prides itself of being a ‘big tent’: I see riders of all genders and ages, on many types of bikes. Not just racing bikes, rando bikes, gravel bikes, old-style touring bikes… but also a recumbent. (No tandem this time, though.) Just as remarkable: Neither the type of bike, nor gender or age, are good predictors of speed and finishing times. And perhaps even more importantly, there are many different approaches to randonneuring. Unlike racing, finishing first isn’t the only goal. Everybody creates their own goals. As long as riders make the time limit and ride the entire course, they get a medal and qualify for PBP.

I enjoy the focus of ‘doing a time,’ as the French randonneurs call it. It’s a rare opportunity to live in the moment, to focus exclusively on my body and my bike. It’s (usually) thoroughly enjoyable, and it most definitely makes for very special memories.

The Tahuya 600 is a classic on the Seattle brevet calendar. Being a spring-time ride, it skirts the Cascade Mountains (still snow-covered in the higher elevations), but there’s more climbing than it looks on the elevation profile. And the jagged terrain toward the end—the infamous Tahuya Hills that gave the course its name—doesn’t look like much on paper, but they are steep and relentless.

Today, conditions look good for a fast time: The forecast predicts tailwinds for the first 300 kilometers, and hot temperatures will make our tires roll faster. (Rubber gets softer with higher temps.) The downside is that the first heat wave of the year poses special challenges to Seattle cyclists: It’s easy to overdo things when your body isn’t used to the heat. And hot it will be, well above 32°C (90°F). Those who try to ride fast will go to the ragged edge of what their bodies can do.

“Self-rescue is the motto for this ride,” cautions the organizer during the brief speech before we start. “At the control in Elma, we’ll have a place to sleep, but if you can’t continue, there is nobody to give you a ride back. Your best bet would be to ride 50 km (30 miles) to Olympia and take the train.” Just in case we needed a reminder that randonneuring is a self-supported sport. Which means we should pull back a bit from the ragged edge. That’s always good advice!

And then it’s six o’clock, and we’re off. We climb across the ridge to Lake Washington and speed along its shores as the first sunlight paints the road in a beautiful komorebi pattern of light and shade. The pace at the front is high—so high that pulling my cell phone out of my jersey pocket to take a few photos immediately sees a gap open. Which is duly closed again…

I am reminded of the start of Paris-Brest-Paris: There are many fast riders, but few will continue at this pace to the end. As my friend (and 12-time PBP rider) Richard Léon once remarked: “Almost as hard as staying with the lead group is deciding when to let them go.”

For now, the paceline offers extra speed, and we traverse the suburbs averaging 32 km/h (20 mph), including a few stretches of gravel trail. One of the fun things of randonneuring is how it compresses space and distance. We’ve only been riding for two hours, and already we are heading into the foothills of Tahoma (Mount Rainier).

As the road turns hilly, the paceline extends and contracts on every rise. That’s natural, as the front riders are already on the downhill while the rear ones are still climbing, but it means a significant increase in effort. This effect is minimized at the front, but that means taking more pulls than I’d like. We’ve covered one hundred kilometers in just over three hours. That’s a little faster than ideal: I won’t complete the 600 km in 18 hours! Nor will anybody else… In fact, most of the riders in this group will sleep at the stop in Elma and finish the ride tomorrow. I plan to keep my stops minimal. Our goals are different, and so will be our speeds from here on. Time to ride on my own.

Orville Road is a perennial favorite, and it’s at its best on a day like this: sunny, but early enough that there is no traffic. The road undulates along a beautiful valley. It’s cycling heaven.

A short climb brings me to Eatonville and the first control. There’s a question that I answer on my route sheet as proof that I’ve been here. (The practice to obtain signatures from businesses was abandoned a few years ago.) Almost reflexively, I walk into the store to buy water. Then I realize I don’t need it—the next control is just 50 km (30 miles) further, and I have a full bottle left on my bike. That should get me there, or at least within close reach. Three minutes saved!

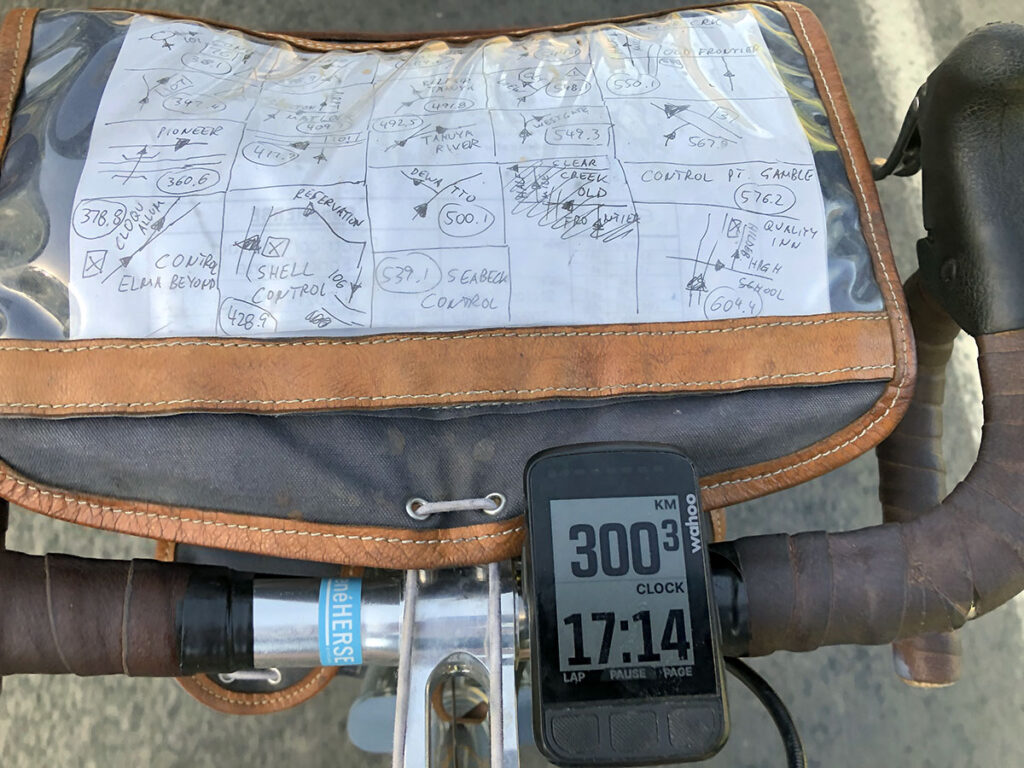

The course climbs through a beautiful valley, but on-the-bike-photos have to wait until the road is flat and smooth. The kilometers pass with pleasing regularity. (It’s a PBP year, so I’ve set my Wahoo to metric. Last year, I went to Unbound XL, so it was miles.) Tahoma is a constant companion, peeking over the hills that surround me.

This area is very familiar, as I’ve ridden these roads dozens of times. Little has changed here over the years, and memories flood back: Ramrod (Ride Around Mount Rainier in One Day) when it was still a timed event, with large pacelines flying across these early hills before the selection happened on the big climbs. Exploring gravel roads on a touring bike with ‘huge’ 35 mm knobbies during my field work for my Ph.D. More recent rides and adventures, including one of the first BQ Un-Meetings, when our team pacelined through here, our bikes loaded with camping gear as we rode into the night to the meeting point in Packwood.

I enjoy the long climb past Elbe. At least I recall it being long. Today, bike and legs work in perfect harmony, and the top appears almost before I expect it. To my left, I see the Sawtooth Range in the distance, a remarkably wild and remote area that has been to focus of many explorations. It took ten years to find a rideable route through those mountains, as so many roads are abandoned, and landslides and washouts have made them impassable. We finally found a beautiful route last autumn, and many readers will have read the story in the current Bicycle Quarterly. Today won’t be quite as adventurous: We’re staying on roads that are known to exist.

My water runs out a few kilometers before Morton, and it’s getting hot. No problem, in 15 minutes, I’ll resupply. Looking back, I see Mark approach from behind. He let the paceline go a little earlier. We roll into town together and stop at the convenience store to refill our bottles. My bike carries two bottles with water and electrolytes, plus one with Ensure Plus meal replacement. This allows me to take in calories on uphills or in pacelines, so my body won’t go into a deficit. My handlebar bag is full of gummy bears, chocolate chip cookies, an Untapped maple bar, dried mango and a few other ‘real’ food items.

Mark is experimenting with carrying even more water than I do. He’s riding strong today. We cross the Cowlitz River, and the road turns upward again. Mark’s pace is too high for me, so I drop back. It’s getting hot, and my body tells me to hold back a bit.

One-third of the ride is behind me. The second metric century took almost four hours, including stops. That’s closer to my target pace, and I’m feeling good about my ride.

The course leaves the foothills of the Cascade Mountains, but already I can see the Willapa Hills on the horizon. I don’t mind: Hilly terrain allows me to stretch my legs on the climbs and rest on the descents. I find hills easier to ride than flat terrain.

There’s little traffic on this course, but the roads are wide and don’t get much shade. Compared to gravel roads under tree cover, I had forgotten how hot it gets above large expanses of pavement. It may ‘only’ be 32 °C (90°F) in the shade, but it’s much hotter just above the road surface.

A fast brevet time relies more on keeping stops to a minimum than on fast on-the-road speeds. But with this heat, it seems prudent to take a few extra rests. A convenience store in Napavine has a few chairs, and I eat an ice cream cone (calories and reducing my core temperature) in air-conditioned comfort. Just 30 km (20 miles) later is Pe Ell, where another convenience store is a welcome opportunity to fill up my bottles. Mark is just leaving as I arrive. He, too, has slowed his pace.

For a long time, I’ve wanted to visit Pe Ell. Many years ago, Bicycle Quarterly published a story written by Al Tietjen, a local historian, whose ancestors lost their fortune when they invested in the Chainless Hill-Climber, a shaft-drive three-speed bicycle, during the early days of the 20th century. Only a single bicycle remains from that adventure, and Al restored it to rideable condition (BQ 23). I wonder whether it’s still lurking in one of the old houses that make up this charming little town in the middle of nowhere.

Did I mention it’s hot today? The road is pleasant, but not very photogenic. The third metric century has taken seven minutes longer than the second, but that’s to be expected with all the extra stops. Even though I haven’t pushed the pace, my legs are on the verge of cramping, despite taking electrolytes in various forms. I remind myself that this means I have been pushing close to the limit, as I intended.

Half the ride is complete. Somehow, the euphoria of riding bikes long distances makes it easy to focus on the positive. It doesn’t really occur to me that, even though I’ve been riding all day, for a little over 11 hours, I still have to ride this far again. The reality is that I’m having fun, and I’m not yet ready for this ride to end.

I run out of water again in the Willapa Hills. Just then, a quaint little restaurant appears, with a take-out window on the side of the wooden building. The window is open, and a handsome young man leans against the wall and chats with an equally good-looking young woman standing inside. The scene looks like it belongs in a movie.

As I roll up, the man says: “We’re sorry, our power is out. We’re closed.”—”Do you have water?” I ask. “Sorry, nothing works.” The woman chimes in: “Let me see if I have any water left in my pitchers.” I hand her my bottle. She comes back with it one-third full. “I’m sorry, this all I have,” she apologizes. “That’s all I need,” I exclaim as I take a sip. “And it’s even still cold!” I thank them and ride off, my pedal strokes invigorated not just from the water, but also the pleasant encounter.

One-third of a bottle gets me to Montesano, another fixture of many brevets. The gas station at the entrance of town looks like an oasis to me on this hot day. I fill up with water, stock up on Coca-Cola, drink a smoothie (more electrolytes), and continue. The shadows are lengthening, but the heat shows little sign of abating. At least there’s a headwind now, which provides a little welcome cooling. Exactly at sunset, I roll into Elma, where the club has rented a few hotel rooms and a banquet area, so riders can spend the night. It’s 8:30 p.m., and the thermometer outside reads 84°F (29°C).

“What would you like?” asks a volunteer as I walk inside and hand over my brevet card. They’ve got food and drink, showers and beds, but all I want is the bathroom to clean my face. It feels good to wash off the salt. I look in the mirror. The face that looks back is a little haggard, but smiling. Not too bad… Once the night gets cooler, I should be fine.

My brevet card is signed when I return. I head outside again. “Mick and Ben just left about five minutes ago,” says Bill Gobie, one of the volunteers. “Who else is up the road?” I ask. “Just those two,” replies Bill. “All the others have decided to rest here.”—”I’ll try to catch Ben and Mick,” I laugh, before adding: “If my legs cooperate.”—”They didn’t look like they were pushing the pace, either,” says Bill, as I ride off into the night.

Night-time rides are magical. The temperature has dropped, and the beam of my Edelux headlight is a welcome change from the glare of the sun. The air smells fresh, and I hear the sounds of animals rustling in the forest next to the road. My legs are feeling better, and I gradually increase the pace.

A little over an hour later, I come across Mick (left) and Ben (right). They’ve just finished shooting a second plug into Mick’s tubeless tire. “I’m not feeling so good,” says Mick as we ride into the night. Mick and I used to race together way back. During my first gravel race—in the days before ‘gravel’ was a thing—we were in a breakaway together with four other riders. Having just returned from a long research trip abroad, I was suffering on the last hills toward the finish. Just then, I felt a gentle push on my back. “You can do it, Jan,” said Mick’s voice quietly. I don’t remember whether Mick won the sprint—he probably did—but his help allowed me to stay with the lead group.

Tonight is my opportunity to repay the favor, but we soon realize that Mick needs some real rest. Where to find a hotel on Saturday night at 11 p.m.? We remember that there’s a big resort hotel just 15 km down the road. The road goes along the water’s edge of the Hood Canal, so it’s one of the few stretches on this ride that is flat. We put Mick in the middle of our paceline, so he gets the draft from the front and an (aerodynamic) push from behind, and we soon arrive at the hotel. Everything is quiet, and the lobby in the main building is occupied by several cats. This doesn’t look good…

Just then, a man walks up. We ask about a room—any room—for our sick friend. “I think we had a cancellation today,” he replies. “Please come to the front desk with me.” With Mick taken care of, Ben and I continue our ride. We fly along the Hood Canal, ride through Belfair without stopping, and reach Tahuya, where our adventure will begin in earnest.

The Tahuya control is another wonderful tradition associated with this brevet. Arriving in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of the night, and being warmly welcomed by volunteers is one of most special feelings I can imagine. Tonight, it’s Rose Cox, president of the Seattle International Randonneurs, and her husband Greg who provide supplies and encouragement—and a bed where I stretch out for a few minutes. This is the first long ride of the year, and I feel it in my legs and arms.

Night-time rides are magical, and none more so than those in the Tahuya Hills. At night, this area feels even more remote than it is in daytime, and tonight there is no moon. Our world contracts to the hills, the trees, and the stars. We climb and descend, climb more, dive down to the water through decreasing-radius hairpin turns (taken slowly, especially at night), climb some more and finally reach a (deserted) highway that starts here and will take us back to civilization. During the two hours it takes us to traverse the Tahuya Hills, we don’t see a single car.

Civilization is relative: Seabeck is fast asleep, and our control consists of answering another question on our brevet card. (Now that the ride is over, I can give away the top-secret information: There are two flower boxes in front of the general store.) The eastern sky across the water is turning orange. I love night rides, but I also love when they are over, and a new day dawns. It’s part of the beautiful passage of time, which we truly feel on this ride: Day is followed by night, which is followed by day again.

Beautiful it may be, but we’ve been awake for almost 24 hours. Ben is feeling sleepy, and it seems prudent to take a rest. But the early morning is chilly… We spot a small building with two doorways under an awning. The two floor mats provide a little insulation, and we stretch out for a ten-minute power nap. Rejuvenated, we attack the hardest and steepest part of the ride: the three-part, stair-step Anderson Hill Road. A sign warns us of the 14% grades—up and down. Even those of us who love climbing don’t like this road, especially since we usually ride it with more than 500 km in our legs. We both tuck in the tighest of aero tucks to maximize our speed on the downhills—Wahoo suggests I reach 92 km/h, but Strava will reduce that to ‘just’ 90.7 (56.4 mph). It helps, we coast up one ultra-steep rise before we run out of momentum. What follows can only be described as a grind up the steep slope… But it, too, passes underneath our tires.

The course takes us north to Port Gamble. We’ve turned off our lights, and it’s already getting warm. My legs finally say “enough” on the last steep, sharp rises near Poulsbo. Ben goes ahead, and I ride across Bainbridge Island alone. And then there is the finish, with cheerful volunteers, who hand me a cup of noodles that tastes heavenly after all these hours on the bike.

My official finishing time is 25 hours 23 minutes. Ben arrived a few minutes earlier. I’m happy, as I’ve pushed myself as hard as I could. Most of all, I had fun.

Ben and I catch the 8:45 a.m. ferry back to Seattle. (The ride ends on Bainbridge Island across the Puget Sound from the city.) Looking over my bike after I tie it to the railing for the ferry ride, I suddenly remember that I’ve been riding on ultra-wide tires. On the road, I completely forgot about that. Whether in the fast paceline at the beginning, during the long solo hours, or in the middle of the night, the bike felt just like a bike.

The ultra-wide tires didn’t hold me back, but they also didn’t provide an advantage. My arms are as tired as I’d expect on my rando bike. Apparently, that bike’s 42 mm-wide tires filter out as much of the road surface vibrations (on pavement) as the 54s. What remains is the inevitable fatigue of pedaling a bike for so many hours. As I glance back, it still surprises me that the same bike could traverse the rough trails and ultra-loose gravel of the Oregon Outback at FKT speeds. I guess it deserves the name ‘all-road bike.’

Then I forget the bike again, as the impressions of the ride flood my brain. I remember the beautiful roads, the long hours doing something I love, the magic night-time ride… and already have almost forgotten the heat and inevitable discomfort during the first long ride of the year. Long-distance riding may not be for everybody, and I wouldn’t want to do a ride like this every weekend. But, a few times a year, these rides form incredible high points that create lasting memories.

Further Information:

My consumption of fluids and calories over those 25 hours:

- 6 l of water with Noon electrolyte tablets

- 2 l of Coca-Cola

- 0.5 l apple juice (calories, electrolytes, but not ideal for my stomach on this hot day)

- 6,500 kcal (260 kcal/hr)

- Ride stats on Strava.

- A technical dive into how wide tires can roll as fast as narrow tires.

- The FKT ride across the Oregon Outback on the same bike.