Racing and Touring: Why-Not-Chee

Summer in the Pacific Northwest is a glorious time, when the days are long, the sky is blue, and the mountains are calling. We answer that call as often as we can, creating memories that tide us over the long and rainy winters, when the high passes are covered under 20 ft (7 m) or more of snow. Events and races are a great way to explore new places, and so I was looking forward to the final race in the Gravel Unravel series: Why-Not-Chee.

The name is a play on Lake Wynochee, an almost-mythical place nestled in the southern Olympic Mountains. Located at the foot of Humptulips Ridge, Lake Wynochee really does exist, but almost nobody has ever been there. The ‘Why-Not’ part of the name is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the difficulty of reaching this beautiful place. Lake Wynochee is 56 km (35 miles) from the next town, on a road that dead-ends at the lake. There used to be a campground, but that closed years ago. Today, there are no services at all, not even water. But Buck and Lorrie, the organizers of the Gravel Unravel series, obviously thought: Why not hold a race in this beautiful, but remote, place?

Buck scouted some amazing gravel roads that go high into the mountains, right on the edge of the Olympic National Park. If you want to go beyond, you’ll have to go on foot. Gravel Unravel got permission to use the old campground and brought in water. I was excited about the opportunity to explore such a remote and beautiful area.

In addition to the paved road that heads to the lake from the south (making for a very long trip from Seattle), there is a gravel road that traces the southern edge of the high mountains. That is the road I was going to take—by bike. I’ve ridden this road a few times, and it’s an absolute favorite of mine. I was excited about the opportunity to ride it as a ‘bonus’ on the way to the race.

That’s how my bike found itself on the Friday afternoon ferry to Bremerton, together with a few commuter bikes and some motorcyclists (plus the usual load of cars and trucks). The decision to take my Oregon Outback Rene Herse for this adventure was easy: It’s the only one that’s equipped with custom-built low-rider racks for my camping gear. I love that this bike can carry a full camping load and then, after removing just four bolts, turn into a gravel racer that tackles events like Unbound XL with confidence.

You don’t need a custom bike for adventures like this: Most gravel bikes can be equipped with bikepacking bags, which is one of the great things about modern bikes. That said, I do prefer panniers unless the trails are so narrow and rough that the low-mounted panniers bottom out. Since I usually go bike camping with Natsuko, our equipment is for two people: Tent, stove, cooking pot all are a bit bigger than single-person items, and the extra capacity of panniers is welcome. I enjoy the ease of packing with just two big (and expandable) panniers, rather than a jigsaw puzzle of multiple small bags. Many bikes could offer the option of mounting low-riders: It’s easy to position the mounts on bikepacking forks so they line up correctly—what matters is the distance between dropout and mid-fork eyelet. That would give riders options: bikepacking bags for adventures that include single-track and other terrain that’s too rough for panniers; low-riders for trips on paved and gravel roads.

Another thing I like about front bags is that they don’t change the feel of the bike. Sure, the extra weight blunts the performance a bit, but there’s none of the tail-wagging-the-dog feel that I get with large rear bags. Even though I’m carrying a camping load, the bike still feels like the performance bike that I love to ride. And, surprisingly, my average speed wasn’t much lower than it would have been on an empty bike.

Forest Road 23 is an all-time favorite. It climbs high ridges and dives into deep valleys, but it’s never so ultra-steep that it becomes a struggle (or forces you to hike-a-bike). The surface is (usually) smooth and devoid of much washboard. When the forest canopy opens up, the views are spectacular. I had gotten a late start, and dusk was falling as I climbed and descended this marvelous road. Toward the end, I saw course markings—this stretch would be part of tomorrow’s race. Even though summer days are long, it was completely dark when I arrived at the start of the race. I pitched my tent, cooked a quick dinner, and went to sleep.

After a good night’s sleep—a 75-mile ride almost guarantees that—I woke up to a beehive of activity. Campers were prepping their bikes. Other racers were arriving after having driven here in the morning.

After removing the four bolts that attach the one-piece low-rider rack, refilling the bottles, and attaching the race number, my bike was ready for the big race.

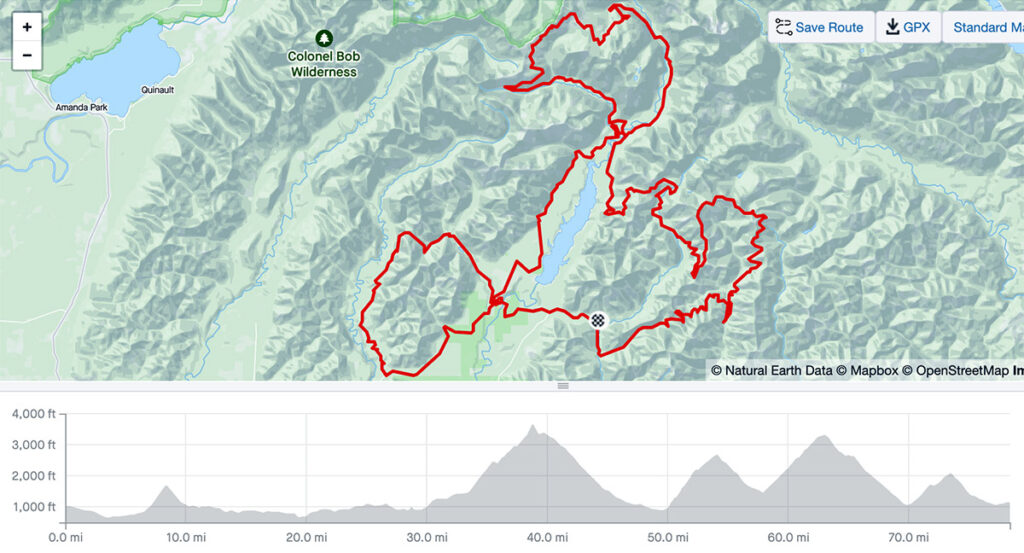

And big it would be: The ‘Long Course’ would cover roughly the same distance as yesterday’s ride (78 miles/125 km), but with twice as much elevation gain: almost 10,000 ft (3,000 m)—all on gravel. Even after seeing the course profile, I think most racers—myself included—underestimated the challenge ahead. I mean, we know what it’s like to race for 78 miles. Make a small adjustment for the extra elevation gain, and things should be fine. Or so we thought.

The pace was high for the first few miles on a wide logging mainline. It continued that way as the peloton threaded onto a narrow double-track that winds up the side of Humptulips Ridge. In most races, that climb—1,000 ft/300 m of steep, rutted gravel two-track with grass growing in the middle—would be the highlight of the race. Here it was just the first little bump in the elevation profile (Mile 8.5). The ride along Lake Wynochee—sadly without views of the water—lulled us into more complacency, until we headed into a 5-mile section of single-track mountain bike trails. Not what you’d expect in your usual gravel race, but great fun nonetheless.

And then we headed into the high mountains. The next climb was the biggest of the race. It started gradual, but got steeper and steeper as we climbed. Climbing 2,700 ft (850 m) on steep gravel without any break was more than most legs could handle. Near the top, our computers showed gradients of 17% and more, and most riders dismounted. I was one of them.

I actually enjoyed that hike-a-bike. It was nice to rest my legs, look around at the incredible mountain scenery, at the wildflowers that were still in bloom at this high elevation—and actually pass a few racers who walked slower than me.

A roaring descent followed. Climbing 17% gravel roads is one thing, but descending on loose and rough gravel that steep is actually more difficult. Knowing that I wasn’t going to win the race, I didn’t take any risks, but I still got up to more than 50 km/h (32 mph) on the short straights between the turns that had me brake at the limit of traction. The descent was exciting, to say the least. Even though it lasted 25 minutes, it didn’t really allow for recovery.

Back in the valley, our course converged with the ‘Medium’ course for about a mile, so I found myself riding with a half-dozen other riders. I passed a water station and decided not to stop. Half a bottle of water should get me through the remaining 25 miles, I reckoned. Except that there were two more monster climbs on the course (plus a smaller one that gained ‘only’ 1,000 ft/300 m).

I made it over the next climb just fine, and the views of Lake Wynochee from the top were truly breathtaking. The descent, on bumpy gravel with occasional washboard, was another 11 minutes of high-adrenaline focus—not enough time to give my legs a meaningful rest before the road pointed upward again.

I ran out of water half-way up the fourth climb. The day was getting hot, but I was confident I’d be able to find water. Soon I heard the gurgling of a little stream, and the lush growth next to the road suggested a small creek. I dropped my bike and climbed down into a little ravine. The water was cold, indicating it had just emerged from the mountain and thus was safe to drink without filtering. I gulped down half a bottle before filling both bottles (my third bottle contained liquid food). I splashed water over my head and soaked my shoes and feet, to cool down a bit. This time, I was not going to take any chances!

After scrambling back up to the road, I continued the climb, much-refreshed. A few minutes later, a car approached from behind. They followed me for a while, until the road got wide enough so they could squeeze by. “Do you need anything?” asked Lorrie, the organizer, through a rolled-down window, as she passed. I was happy to say that I was fine. Solving problems without outside support is always gratifying.

The climb felt like an hour. Usually, that means, in reality, it was about 30 minutes long. This time, Strava shows it took 1:15 hours to get to the top. That includes my water stop, which according to Strava took a little over 2 minutes. A volunteer was stationed near the top. By now, my two bottles were almost empty again, and he urged me to refill. “Do you have some food?” I asked. My own supplies had run out, as I had consumed far more calories than I had planned. I had packed for a typical 78-mile race…

The volunteer handed me a cookie. It was obvious that he’d brought it for himself to eat, and his generosity touched me. The top wasn’t far after that, and the course soon rejoined Forest Road 23, where I had ridden just 16 hours earlier. My legs were tired, in fact, my speed in the race was slightly slower than it had been the night before with a full camping load. On the last downhill, I overlooked a big rock and pinch-flatted on the rear with just a few miles to go. A quick change of tube, and then I rolled across the finish line.

After such a big effort, I’m usually glad to reach the finish. And yet, I am even more glad that I started the ride. I am exhausted, I’m tired, but there are no regrets. The views, the challenge, the feeling of pushing myself to the limit, the adventure—all leave indelible memories. I probably wouldn’t have got to know this remote part of the Olympic Mountains if it hadn’t been for this amazing race. I know I’ll be back—if I do only one race next year, it’ll be this one!

Epilogue 1: The results sheet shows that I finished 7th in the race, and 2nd in the overall series.

Epilogue 2: If you’re wondering whether a bike designed for 24-hour-plus ultra-races is ideal for this event, the answer is: “Not really, but it worked fine.” I didn’t mind the downtube shifter for the rear and direct lever for the front derailleur, as the climbs were long and there wasn’t that much shifting on the roughest sections (except on the twisty single-track, where bar-mounted shifters would have been preferable). I did wish for a lower gear, though. The 26×26 was not quite small enough for the steepest climbs. I was happy with the canti brakes: The direct connection from rim to brake lever gave me the feedback I needed to avoid locking up the wheels on the loose gravel. That said, discs would have been fine, too. Hauling a generator hub and lights wasn’t really necessary in a race that finished long before dark, and the aero fenders didn’t provide much of an advantage on a course that was mostly up or down—the uphills too slow for aero to matter; the downhills so fast and loose that I was braking anyhow. I was happy with the ultra-wide 54 mm tires and a fork that offers a little suspension. In the end, the bike acquitted itself surprisingly well on a course that was much steeper than what it is designed for.

More information: