Sleeping Beauty: Riding a Rene Herse in Paris

Winter is coming to Seattle, but, contrary to stereotypes, it’s not always raining. Sunny days invite us to explore neighborhoods we usually don’t visit. Last weekend, I decided to ride a bike that brings back many memories: The Rene Herse I used for years to commute around Paris.

Back then, I went to Paris every winter for five or six weeks to research the French constructeurs, and René Herse in particular. I visited old riders and employees of the great builders. I spent many hours with Ernest Csuka at Cycle Alex Singer as he initiated me in the secrets that made his bikes special. I worked with photographers and other collaborators on our books. Lyli Herse and I had just found two suitcases of photos – the Rene Herse archives – and we were now working on identifying the people and events they depicted. It was an exciting time of discoveries, and it involved going all over Paris.

My friend Hervé, whom I met during my first ride in Paris-Brest-Paris, graciously allowed me to sleep on his couch for weeks at a time. He also found me a bike…

Hervé was touring during his summer vacation when he noticed an old man and two kids ahead, climbing a hill. The kids were on mountain bikes, but the gentleman was on a René Herse. “Nice bike,” Hervé mentioned when he caught up. “Ah,” said the man, “it’s just an old bike that I bought.” Hervé mentioned that René Herse bikes were quite special, and if he was selling it, Hervé would be interested. He left his phone number with the gentleman, and continued on his ride. He told me about this encounter during one of our frequent phone calls, and then we both forgot about it. Until I returned to Paris the following winter, and Hervé took me to the basement of his apartment building. “The old man did call me after all,” he said as he swung open the door to his garage. And there was the bike…

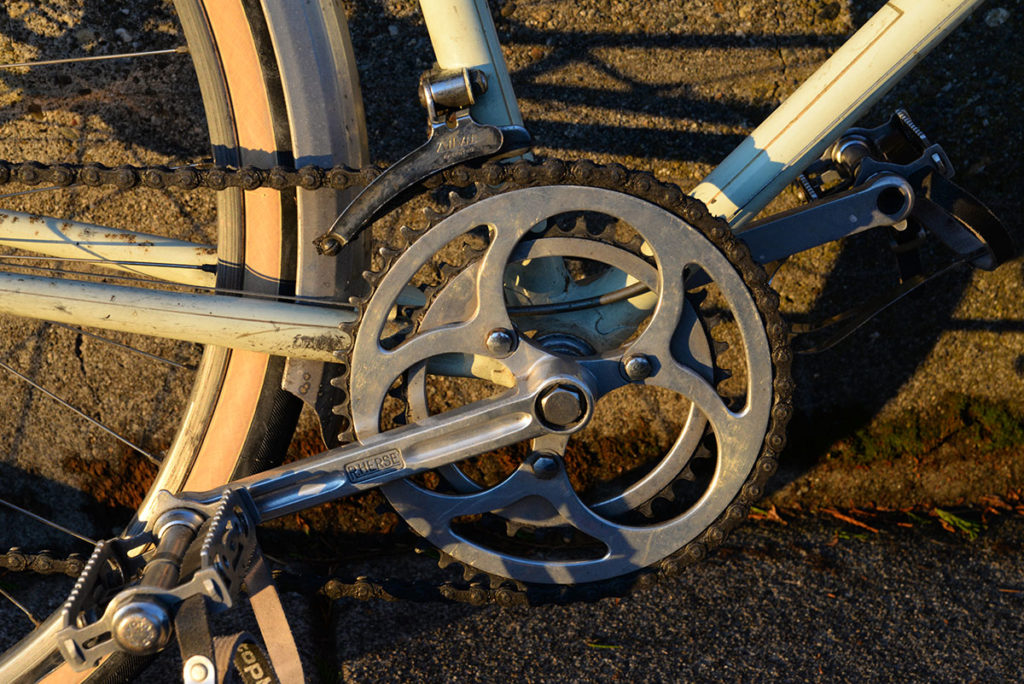

It was a René Herse from the classic days of the ‘Magician of Levallois,‘ a late-1940s Cyclotouriste with 650B x 42 mm tires. The color is unusual, much lighter than the bleu Herse (René Herse Blue) that was popular at the time. The greenish tint may just be yellowing of the paint, or perhaps it was always this color. This has all the special Herse features – the cranks and brakes, the iconic stem, the bottom bracket with pressed-in bearings, but also small details like the light mount (hollow so the wire runs inside) and the elegantly reshaped fender ends. A small front rack is designed to support a handlebar bag. A large rear rack can carry panniers. (Herse himself preferred to carry his camping load in front panniers only, even on his tandem, but not all customers were ready to forego a rear load.)

The bike weighs 11.99 kg (26.4 lb) – respectable for a fully equipped bike even today. Deduct the big rear rack, and you get the same weight as Herse’s lightweight Randonneuses – indicating that tubing selection and other details were the same. (The model names in Herse’s catalogues were just suggestions – each bike was custom-built to the owner’s specifications.)

Most of all, the bike was my size. “You’re welcome to use it while you are in Paris,” said Hervé. Considering that the next Métro station was a 15-minute walk from Hervé’s place, I gladly accepted his invitation. Riding on the streets of Paris is much more fun that sitting on a train that slowly moves underneath the city. Everything on the bike worked as well as it had when the bike last visited Herse’s shop many decades ago. Even the lights – important when riding in city traffic during the short winter days. René Herse ran all the wires inside the frame, the fork, the fenders and rack tubes, where they are well-protected. As long as nobody disassembles the bike and breaks the wires, they continue to work…

Every morning, I rolled down the hill, rode through the Bois de Bologne, rounded the Arc de Triomphe with its crazy traffic, and then descended the Champs Elysées on the smooth cobblestones that feature at the end of every Tour de France. I traversed the river Seine, pedaled past the Louvre, jockeyed with buses and taxis in the Cartier Latin, and then headed to the working-class quarters where most of my acquaintances lived.

It was a fun commute, and the Herse rode as well as you’d expect from a top-tier 650B bike. It flowed easily with Paris traffic. Amazingly, despite not having seen any maintenance in decades, everything worked well. The brake pads were a bit hard, so braking performance was not quite as good as it would have been with new pads. Fortunately, Paris traffic is mostly about jockeying for position, and hard braking is required only rarely. And the brakes were adequate for that.

Many features date the bike to around 1948. It was rebuilt in the 1960s with Huret Allvit derailleurs to replace the original derailleurs. The work was done by Herse himself, who brazed a hand-made derailleur hanger to the dropout, so cleanly that you can’t see where the old dropout ends and the new hanger starts. (Many other 1940s classics were ‘modernized’ much less sympathetically by other shops…) When the bike was updated, it also acquired its current paint with the then-current ‘René Herse’ logo.

The Allvit rear derailleur isn’t elegant, but it works well. This was only the second derailleur that followed the contour of the freewheel to optimize shifting performance. (The first was the Nivex.) On the Allvit, a steel arm extends downward from the dropout, and the parallelogram is hinged from the bottom. (Contemporary derailleurs from Campagnolo and others were hinged at the top, so their chain gap got larger as you shifted to smaller cogs, the inverse of the Allvit.) The unsightly steel arm makes it possible to mount the Allvit on the dropout, whereas the Nivex had to be mounted on the chainstay.

The Allvit fills an important place in derailleur history: It inspired SunTour, who first copied the Allvit and then improved the design with the slant parallelogram, which keeps the chain gap constant without the long steel arm. And the slant parallelogram is still used today by all racing derailleurs for double chainrings.

I rode the old Herse not just for commuting, but also for training. For more than a century, cyclists in Paris have trained on the road that goes around the horseracing track at Longchamps. The road is closed for cars, and you’ll always find cyclists doing their laps. Some are recreational riders; others are racers. One cold winter morning, I was warming up, when a pack of about 30 riders came up from behind. They were riding in a smooth rotating paceline. Clearly they were riders who knew what they were doing.

With a friendly “Bonjour,” I jumped into the group. This was long before gravel bikes were a thing, and here I was on an old steel bike with huge tires, fenders and racks. Toeclips, too! Clearly not what racers would have considered a performance bike. My new companions did not return the greeting. Instead, the pace picked up a notch. No problem, I shifted to the largest gear and spun along with the group, taking my pulls at the front.

The pace picked up another notch, then even more. Now I was spinning at 120 rpm on the flats, as the Herse wasn’t geared for such speeds. When I dropped back after taking my turn at the front, I noticed that our group had lost about half its riders. And still nobody spoke. We continued to race along for another 45 minutes, then it was time for me to return to Hervé’s place for lunch. As I pulled out of the group and thanked the riders for the great workout, I noticed that only 5 remained. Still not a word… I wondered whether they later made a pact never to tell anybody about the guy on the ‘grandpa bike.’

It would be nice to think that I was a stronger rider, but the truth is that my bike didn’t give up any significant performance to their state-of-the-art racing bikes.

Every Sunday, I joined Ernest Csuka and his friends from the Amicale Cyclotouriste de la Banlieue Ouest (Cyclotouring Friends of the Western Part of Paris) for all-day rides that were full of joyful banter and memories of long-gone days. I rode the Herse on the Rallye Singer, the annual ride organized by the shop. After battling it out with the Ernest’s son Olivier and his racer friends on the hills of the Chevreuse Valley, we had lunch with all the friends of the Maison Singer. That was the last time I saw Ernest Csuka, whose health was declining. I cried when I said Good-Bye, knowing that I probably would not see him again. And on the way home from that lunch, a spoke broke in the rear wheel of the Herse. It was as if an era was coming to its end.

My friend Hervé told me he was moving away from Paris, and didn’t have use for the old Herse. I bought it on the spot. The price reflected our friendship, so it feels like the bike is not really mine, and I’ll never sell it. My research in Paris was complete, and our book René Herse • The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders was published a little later. I was glad that I had the opportunity to be there and meet all these wonderful people. Their help and generosity laid the foundation to where Rene Herse Cycles is today. They inspired us to search out long-forgotten mountain passes – and discover the joys of riding on gravel roads. They told me about the supple and fast ultra-wide clinchers of the 1940s that inspired us to research tire performance. And bikes like my Paris ‘commuter’ have served as a blueprint for modern all-road bikes. Not just for steel bikes like my Oregon Outback Rene Herse – the latest carbon gravel bikes also trace their ancestry to these mid-century bikes that combine comfort with speed and rolled on wide high-performance tires.

The old René Herse has lived in Seattle ever since, rarely ridden, because there are other bikes that work better for the rides I usually do. Taking it out this weekend brought back memories of a time when we rode across the wet cobblestones of Paris on cold January days, on the way home from meeting people who had experienced the mid-century golden age of all-road bikes. It was an exciting time of discovery, and it’s even more exciting that, today, bikes with wide tires and luggage are once again considered performance bikes. Back then it was randonneuring, now it’s bikepacking, but the spirit of discovery combined with spirited riding is the same.

More information:

• Our book René Herse • The Bikes • The Builder • The Riders