Staying Ahead of the Tour de France

In France right now, the Tour de France is omnipresent. That’s not an overstatement. Almost everybody, whether they are sports fans or not, follows the Tour. It’s not just the racing, but also the beautiful images. The Tour is a carefully choreographed show of French landscapes and sites, with the bike race tying it all together. You’ve seen the images: Racers riding through fields of yellow sunflowers, past old chateaus, through picturesque villages and verdant mountain valleys. Alpine backdrops and, of course, the forbidding slopes of the Mont Ventoux.

French newspaper headlines talk about the Tour, as do the daily sports papers, of course. In the places where the Tour passes, shop windows are decorated with little racer figures. You overhear people in a small épicerie (grocery store) discuss the chances of a dark-horse contender. If you enter a brasserie (brewery/eatery), there’ll be little else talked about.

Every Tour is like an ancient Greek drama, full of emotion and unexpected plot twists. Some editions are more exciting than others, but all are fun to follow. This year is shaping up to be a classic. Seeing the peloton wind its way across France reminded me of the time when I was in France in July and encountered the Tour at every stage of my trip. And with the Tour came road closures. It was key to stay ahead of the racers, so I could complete the rides and travels that I had planned.

The main reason for my trip to France is to ride the Raid Pyrénéen, a 720 km (450 mile) ride from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, climbing 18 big cols of the Pyrenees along the way. It’s a wonderful ride, tracing many of the routes that the Tour takes every year, but non-stop.

Vacation time in Europe has not yet begun, so the Pyrenees feel very empty. As I climb the Aubisque, the only sounds are cowbells—and my breathing as my bike climbs the steep slope. Even though the mountain is deserted, the buvette (café) on the pass is open. As I enter to have my card signed as proof of passing, a TV shows the finish of that day’s Tour de France stage in Montpellier. It is surreal to see the racers sprint among throngs of spectators just seconds after I have climbed this famous col in complete solitude.

A little later, as I reach the top of the Peyresourde in the middle of the night, I am reminded that the Tour will come here next. The road will be closed in two days for the big race. What are now empty roads will soon be lined with spectators. Racers, team cars, police motorcycles and camera vehicles, the advertising caravan, helicopters overhead—it will be busy here.

Some are already here! Just beyond the crest, camper vans are lined up to catch a good view of the race. There are still a few spots left, but they’ll surely fill tomorrow. For now, everything is still quiet up here at 1,569 m (5,148 ft). I hope my camera flash doesn’t startle the fans during the dark night, with just the moon and stars for illumination.

After completing the Raid, I take the train to Montpellier to visit a childhood friend. The Tour just left this morning, heading the other direction. Shop windows still display little figurines of cyclists sprinting for the finish line (top photo).

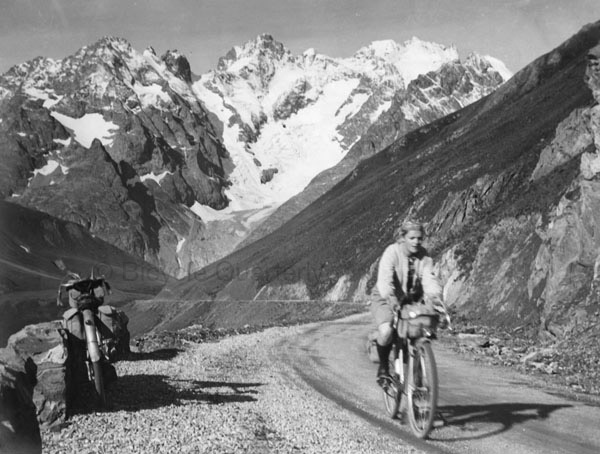

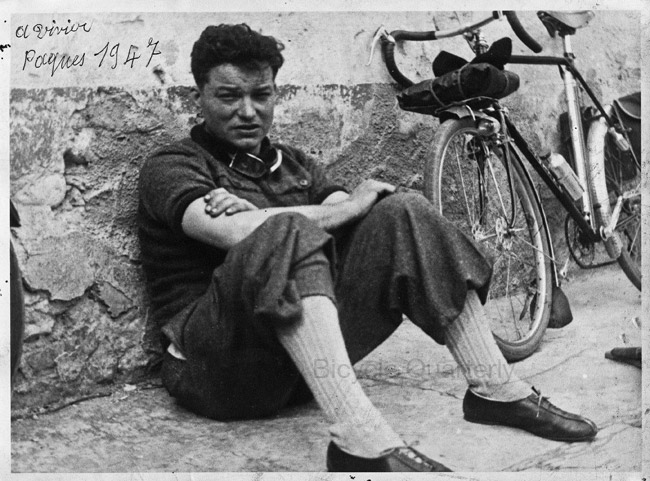

From Montpellier, I ride across southern France to visit Paulette Porthault, the randonneuse who will celebrate her 100th birthday in a few days. We chat about the Tour, and she reminisces about the days when she climbed all the great cols—above she’s on the Galibier in the 1930s. It’s great to see her again. We rummage through boxes of photos, brevet cards and other mementoes, and my visit takes much longer than planned. When I finally leave, I have to hurry to make it to my next stop. As I race across the mountains of the Massif Central, I am greeted by signs: This road will be closed in three days for the Tour.

My hotel serves dinner until 10 p.m., and it’s 9:58 when I pull up and rush in. The kitchen is about to close, but they quickly fix me a big meal. Now off work, the staff comes over and tells me how excited they are about the Tour stage that will finish on the street in front of the hotel. They’ll be lining the road to see the spectacle, but I’m going to be far away already. The Tour is ever-present during my travels, yet I haven’t seen any trace of the actual race yet.

My next trip is to Grenoble to meet the son of the great constructeur Paul Charrel. Charrel didn’t just build amazing bikes, but he was also a keen rider. His dream of riding from his workshop in Lyon to the top of the Mont Ventoux and back in 24 hours inspired our original Cyclos Montagnards Challenge (Seattle to the highest roads on Loowit/Mount St. Helens and Tahoma/Mt. Rainier, and back, in 24 hours).

“Let’s go for a ride,” suggests Frédéric Charrel as we chat about his father’s bikes and artistry (and many other things). “Why don’t we climb the Alpe d’Huez?” I haven’t brought my bike… “No problem, you can ride my son’s.” We load the bikes into Frédéric’s car and head into the Alps. Soon there’s a big traffic jam: The most-anticipated Tour de France stage will end at the Alpe in two days, and spectators, vendors, media and what seems to be half of France are heading to the small ski resort. We’re still about 20 km from the big climb, but we park the car and continue on our bikes. On the narrow shoulder, we can ride much faster than the stop-and-go traffic.

The actual climb is already closed for traffic. Only media and race officials with special passes are allowed. Which means anybody wanting to spectate is already here. The mountainslope is a beehive of activity. Camper vans have already taken every available spot along the road. Barbecue grills are fired up, music is blaring, children and dogs are running around—it looks like any popular European vacation spot in summer, except there’s no beach nearby.

Hundreds of cyclists from all over the world climb the mountain. Some are weaving all over the road as they struggle with their pro-level gears. Everybody is in good spirits. Climbing this steep mountain gives us a feel for the athletic prowess of the racers, who’ll make it seem almost easy in two days—at much higher speeds.

Just before a hairpin, a photographer takes my picture. Seconds later, after I round the curve, he is sprinting next to me, having short-cut the bend. He hands me his card before racing back down to repeat the process with another rider. Later I’ll order the photo on his website. There are a few more photographers, and I soon get used to heavy-set, middle-aged guys running next to me and handing me cards. I almost feels like I’m a racer in the Tour, getting a push from the crowd.

Then we’re at the top. A sign marks the place where the finish line will be. The ski resort is brimming with people. The pastures above the village have been converted into an overflow campground for those who could not park alongside the course.

We notice that the road continues beyond the village. There is almost nobody up here. It’s just a nice little mountain road that leads to a picturesque lake. As much as I enjoyed the atmosphere of the Tour, this was more my style of riding. All too soon, it’s time to turn around, descend the famous 21 hairpins, and head back to Grenoble.

The game of staying barely ahead of the Tour continues when I rent a car in Grenoble to visit Lucien Détée, another rider on the Herse team during the 1950s. As I enjoy my Alfa Romeo Guilietta—rental cars in Europe can be fun!—on small mountain roads near Annecy, I see a sign: This road will be closed in a few days for—you guessed it—the Tour de France. Wherever I go, it seems the Tour is breathing down my neck. I start to feel like a rider in a long break-away, desperately trying to avoid getting caught by the racing peloton.

Finally, I return to Paris at the end of my trip, and the Tour catches up with me, during its very last stage. I’ll spend my last day in France riding with the ACBO, the club of Cycles Alex Singer. As I ride from my hotel to the Singer shop, I cycle up the Champs Elysées. The Arc de Triomphe is bathed in the orange light of the sunrise. I imagine Greg LeMond speeding past here as he eked out his 8-second victory in 1989. Today the Tour will finish here again. Barriers are being installed to keep the spectators off the road, and TV trucks are positioning themselves for the evening’s race.

With the Alex Singer riders, we spend the day on narrow backroads that undulate through the hills near Paris. The big city and the Tour de France seem far away. It’s one of those rides that remind me what cycling is all about.

When I return to Paris in the afternoon, the Champs Elysées have been closed off completely. Police are patrolling the street. The sidewalks are crammed with spectators, even though the racers will not arrive for another six hours!

It strikes me how big a production the Tour de France really is. Sidestreets are packed with police cars, hundreds of them. Most of central Paris is closed to traffic. For now, I’m able to pass on my bike. I decide that I’ll come back tonight and watch the final moments of the Tour, after trying to stay ahead of the race for weeks now. After a great dinner in a little restaurant, I return to the race course.

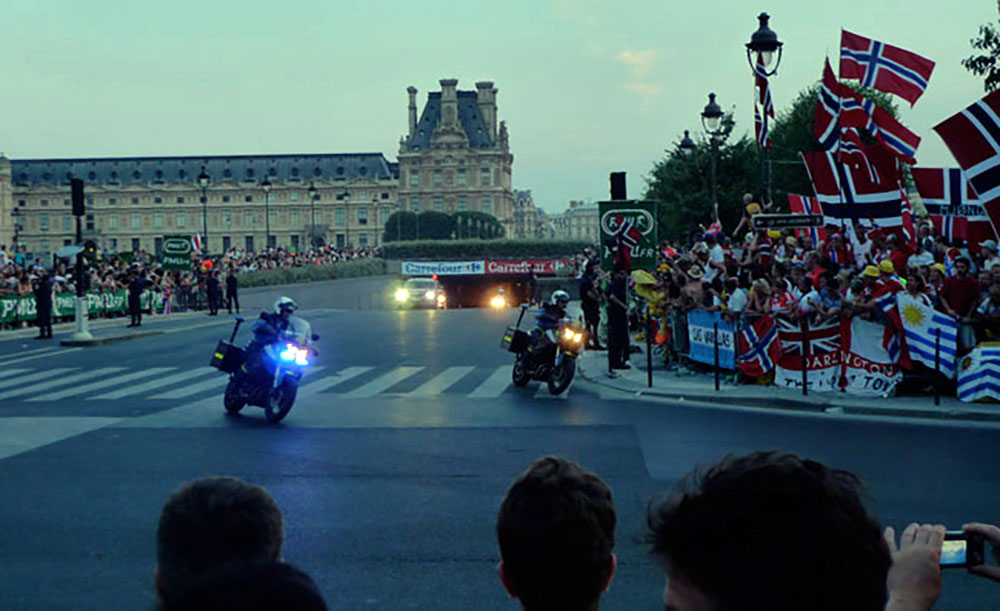

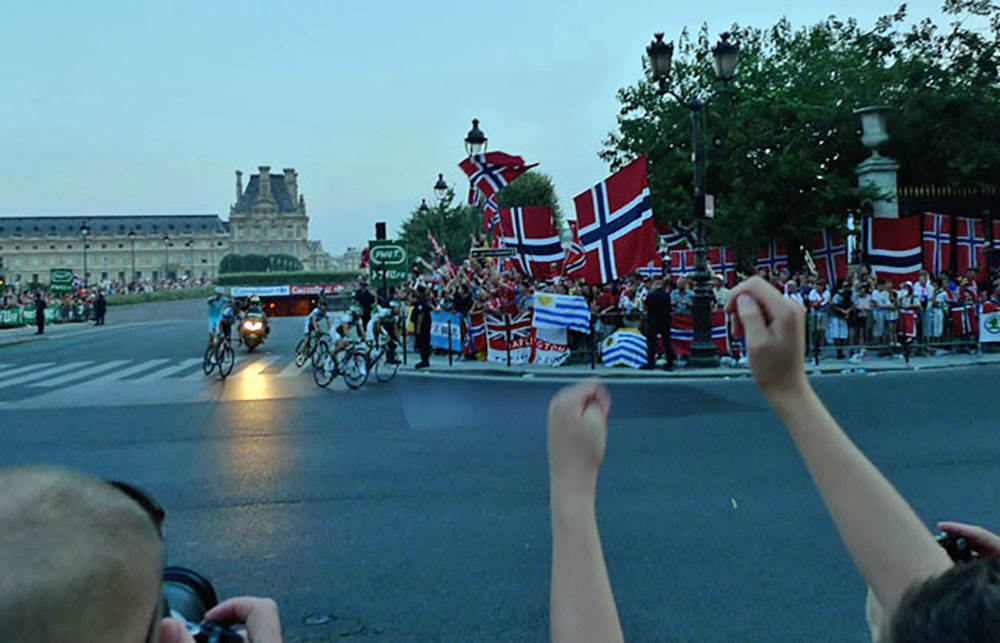

The sun has already set when I find a spot in the last corner of the race, just 200 meters from the finish line. Across the street is a large Norwegian contingent waving flags, plus fans from other nations. I arrive just in time to see the police motorbikes open the road for one of the last laps around the course.

Three riders have broken away! They are going fast! What a buzz it must be to race ahead of the peloton and climb the Champs Elysées while all of France is watching.

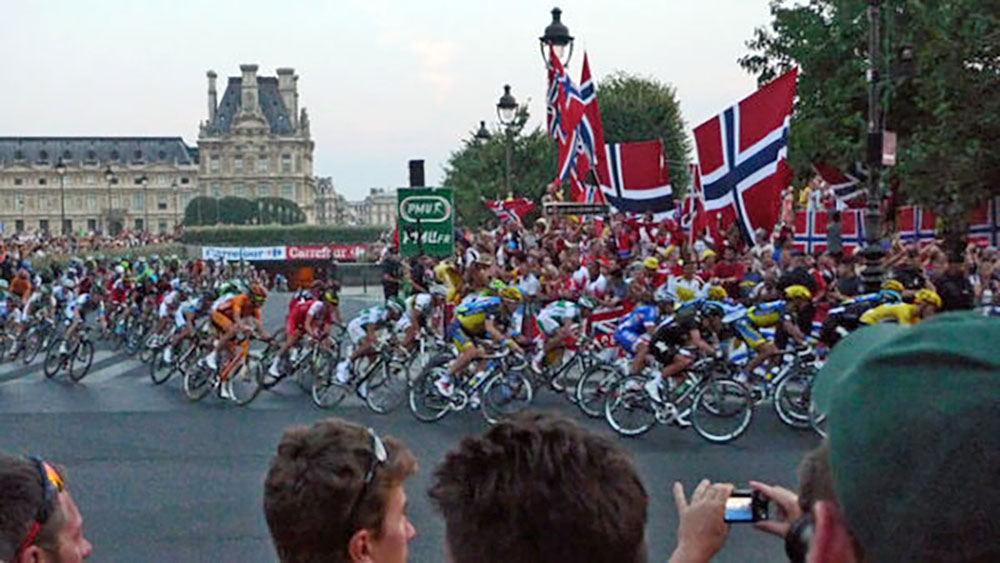

Then comes the peloton. I spot the yellow jersey (on the right). The racers go by in a blur. A few minutes pass, and they come around again. The breakaway has been swallowed by the peloton. I realize that the Tour has caught up with me, too. Like the breakaway, I have been overtaken by the speedy racers.

This is the last lap. The spectators around me rush to a bistro behind us, where a TV screen shows the finish. By the time I turn around, it’s already over. The sprint lasted just a few seconds. I’ll find out tomorrow who won this last stage.

The spectators are not heading home yet. There are still riders on the course, groups who have been dropped in the mad dash to the finish. Probably the riders from that early breakaway are among them. In a moving display of sportsmanship, the spectators applaud these riders with even more enthusiasm (and decibels) than the leaders received.

Finally, here is the lanterne rouge, the very last rider, followed by the broom wagon and an ambulance. From a sporting perspective, the race is over once this rider has crossed the finish line. But there is still more to come.

There’s a long parade of team cars. They carry the spare bikes needed in case a rider has a mechanical problem. Then comes a tow truck that follows in case a team car has a mechanical problem. And then the Tour de France is really over. After weeks of anticipation, the whole spectacle has lasted no more than 10 minutes.

As I ride back to my hotel in the working-class quartier near the Porte de Vincennes, the full moon rises above the Ile de la Cité. The Tour de France now seems almost like a strange dream. What remains real are my own rides around France, the people I’ve met, and the memories we’ve shared.

Further Reading:

- The ride in the Raid Pyrénéen is written up in Bicycle Quarterly 38.

- Paulette Porthault died in 2019, aged 105. The story of her life was published in Bicycle Quarterly 71.

- The story of Paul Charrel, the constructeur from Lyon, is in Bicycle Quarterly 30.

- For more information about riding the Raid Pyrénéen, check the website of the organizer, the Cyclo-Club Béarnais.

Photo credits: Jered Gruber (Photo 2); Griffe Photo (Photo 8); all used with permission.