How to Test Tire Performance

In the 15 years of Bicycle Quarterly, one of our discoveries has been that testing bicycle performance isn’t easy, and that taking shortcuts often has led to erroneous conclusions.

Carefully designed tests that replicate what happens when real cyclists ride on real roads have allowed Bicycle Quarterly to debunk several myths. Certainly, the biggest change in our understanding of bicycles has been about tires.

Tires, more than anything else, change the performance, feel and comfort of your bike. We now know that fast tires can increase your on-the-road speed by 10% or more. But how do we know which tires are fast?

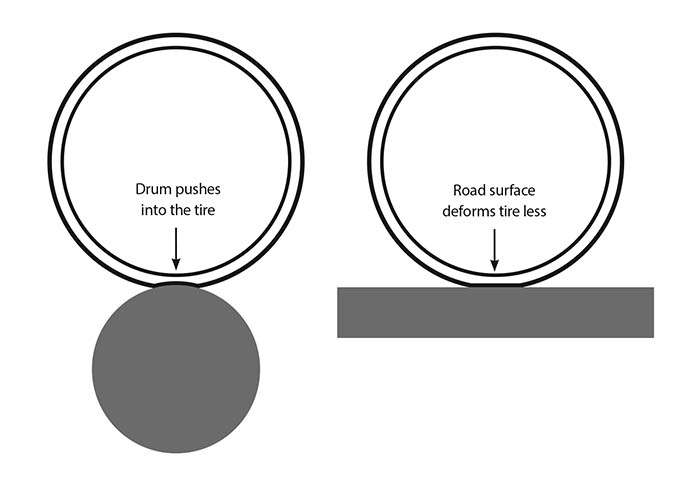

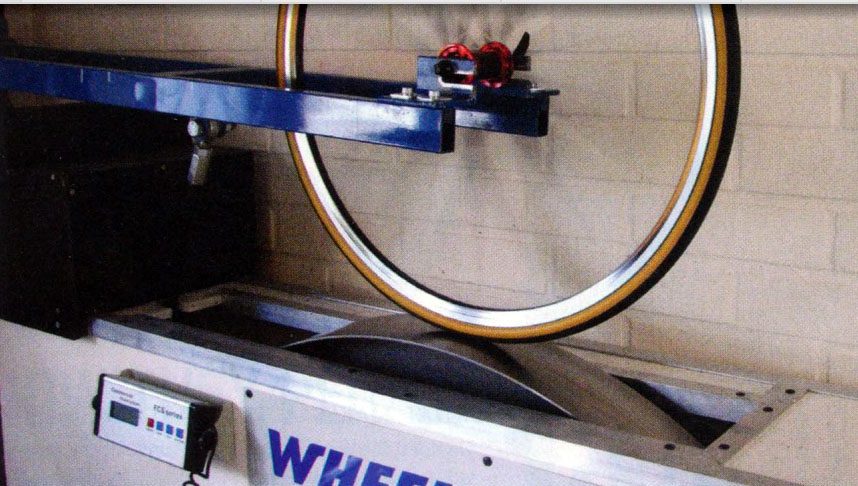

Lab testing is the most common way to test tire performance, usually on a steel drum (above). In the past, these steel drums were smooth. Now the testers have added some texture to simulate the roughness of the road surface. Unfortunately, that doesn’t address the fundamental flaws of drum testing:

1. The curved drum pushes deep into the tire

Since the drum is convex, it pushes deep into the tire, unlike a real road, which is flat. The more supple the tire, the deeper the drum pushes. This makes the tire flex more, which absorbs more energy. That is why a stiff tire performs well on the drum, and a supple tire does not. We know that the opposite is the case on real roads.

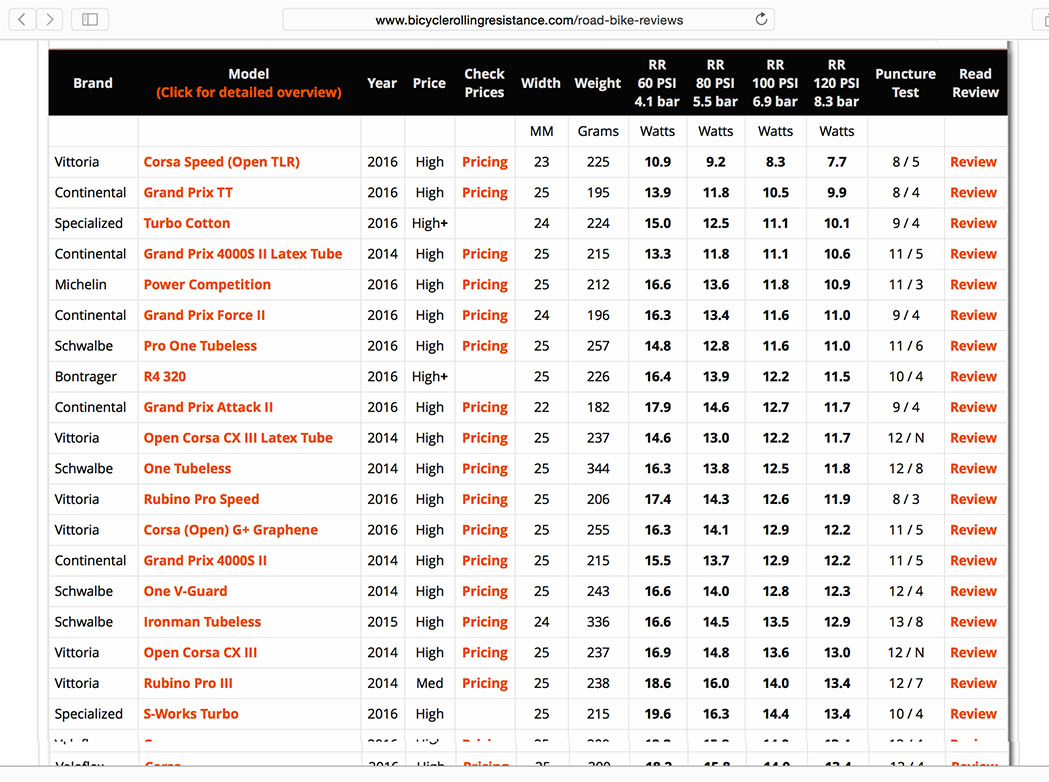

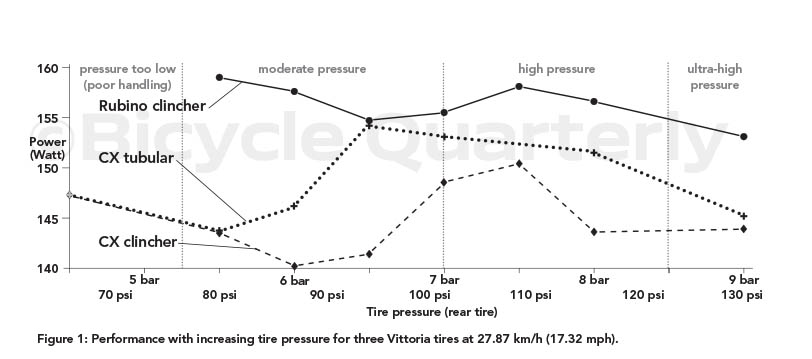

Increasing the tire pressure also makes the tire harder, and so the drum won’t push as far into the tire. That is one reason why drum tests show higher pressures rolling much faster (above). According to this data, increasing your tire pressure from 60 to 120 psi (4.1 to 8.3 bar) reduces the resistance by 30%!

Bicycle Quarterly‘s real-road testing (above) has shown that the opposite is true, especially for supple tires: They roll slower at 100-120 psi than at lower pressures. (Higher power = slower.)

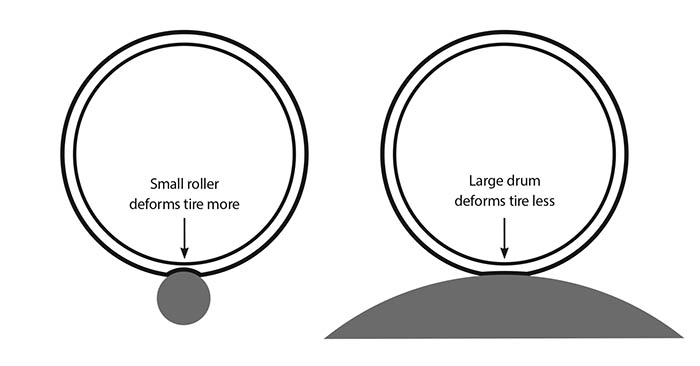

This problem with drum tests has been recognized for a long time. There is a way around this problem, but it’s very expensive: Make the drum so large that it’s barely convex. One of the best drum testing rigs is in Japan, and from what I’ve heard, it measures about 7 feet in diameter. That means it’ll push into the tire much less, and thus it won’t make stiff tires seem faster than they really are.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have efforts to measure tire performance on small-diameter rollers, like those used for training. That will always be futile: Anybody who has ridden on rollers knows how high the resistance is, because the rollers push so deep into the tires. And if you want to increase the resistance further, you just let some air out of the tires…

Not surprisingly, tests on small-diameter rollers show the ultra-supple Compass ‘Extralight’ casing rolling not much faster than the ‘Standard’ version. On real roads, the performance difference between the two is quite noticeable.

TOUR magazine in Germany has designed a test rig that eliminates the problems associated with the convex drums: Two wheels carry weights that are off-center, so they rock the wheels like a pendulum. This test rig rolls back and forth on a flat surface. You could even use it to test on real roads. The longer the test rig rocks from side to side, the lower the tires’ rolling resistance.

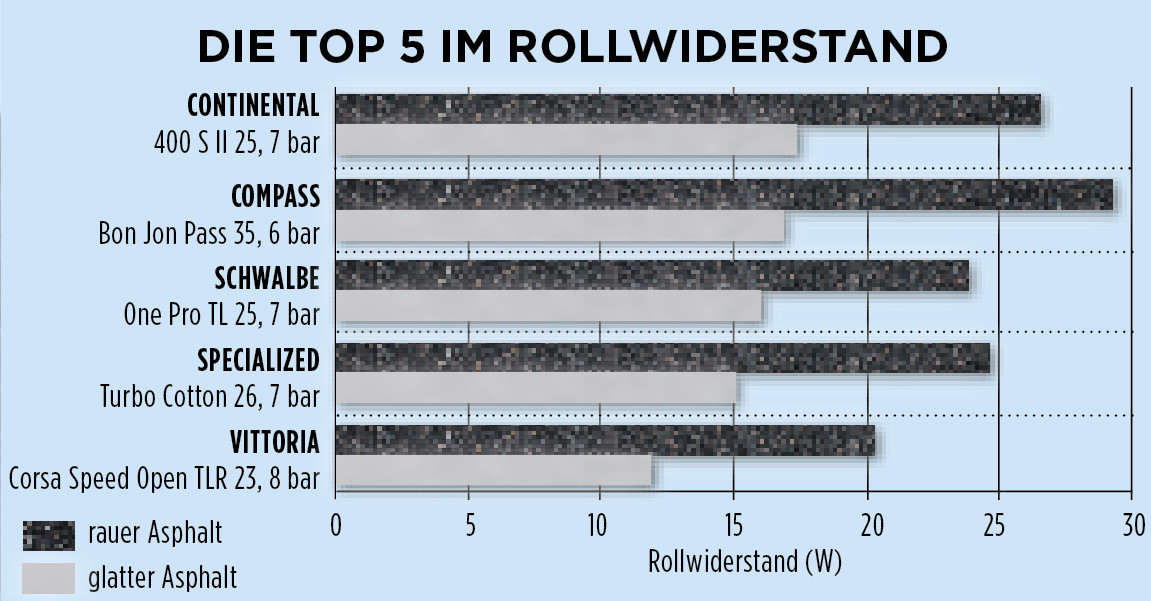

This test showed the Compass Bon Jon Pass as the fourth-fastest tire they’ve ever tested. (‘Rollwiderstand’ means ‘rolling resistance;’ the dark bars are for ‘rough asphalt;’ the light ones for ‘smooth asphalt;’ to convert the pressure from bar to psi, multiply by 14.5)

It’s interesting to compare the same tires – Compass Bon Jon Pass 700C x 35 mm tires (standard casing) vs. Continental 4000 S II in two tests:

- www.bicyclerollingresistance.com tested on a steel drum:

- Compass (6 bar / 90 psi): 15.8 W

- Continental (7 bar / 100 psi): 12.9 W

- Conti has 18% lower rolling resistance.

- TOUR magazine used their rocking test rig:

- Compass: 17 W

- Continental: 17.5 W

- Conti has 3% higher rolling resistance.

- Compass is fourth-fastest of all tires TOUR tested (graphic above).

It’s clear that the drum test disadvantages a supple tire – the stiffer Conti performs much better. Adding to the confusion, www.bicyclerollingresistance.com gets lower resistance values than TOUR – it should be the other way around with the drum pushing into the tire.

There is another odd thing: TOUR shows the wider Compass tire in 4th place on the smooth road surface, but in 5th place on the rough surface, where it gets beaten by the narrower Conti rolling at higher pressure. That isn’t how it works in the real world, where the advantages of wider tires and lower pressures are greatest on rougher roads. That brings us to the second problem of these lab tests:

2. No rider on the bike

Without a rider, you have no significant suspension losses. Suspension losses are the energy that is absorbed when vibrations cause friction between the tissues of the rider’s body. Without a rider, there is nowhere to absorb the energy – steel weights don’t behave like human tissue.

Without suspension losses:

- vibrations wouldn’t slow you down.

- wider tires would be slower than narrow ones.

- higher tire pressure would make your bike faster.

On the road, with a rider on board, all these statements are false – because suspension losses absorb energy, and reducing suspension losses is key to making a bike go faster. Understanding suspension losses has revolutionized our understanding of tire performance. It’s the underpinning of the ‘wide tire revolution.’

The lab tests described above are like a return to the last century, when we all ‘knew’ that narrow tires rolled faster because they could run at higher pressures. So we ran 19 mm tires (above) and inflated them rock-hard for optimum performance. That was long ago – when did you last see a short-reach racing brake with so much tire clearance?

Today, even professional racers run 25 mm tire at 80 psi. They have found that this is faster, no matter what the steel drum tests say. Racers have concluded: When tests don’t replicate the real world, they aren’t of much use.

At least TOUR‘s test rig gives us some indication about the energy absorption in the casing. It neglects one half of the equation – the suspension losses – but it’s useful if we understand its limitations. On the other hand, tests on small-diameter drums are just misleading – because if you design a tire to perform well in these drum tests, it’ll have a stiff casing and ultra-high pressures. And that means it won’t perform well on real roads.

A better lab test?

Is there a way to design a realistic lab test for tire performance? After all, Bicycle Quarterly‘s test procedures – testing only on totally calm days; when temperatures are constant; with a rider who has trained to keep the same position for lap after lap – are fine if you are doing scientific research. But they are not feasible for commercial applications, where you need to be able to just mount a tire on a wheel, take it to the lab, and get an immediate reading of its performance – without having to wait until the weather is right, the wind has died down, and the temperature is constant.

At Bicycle Quarterly, we’ve been thinking about this. Current drum tests load the tire with metal weights that don’t absorb much energy as they vibrate. Is there another material that behaves similar to a human body? ‘Ballistic gelatin’ is used to simulate gunshot wounds in human tissue. It closely simulates the density and viscosity of human tissue. Using a material like that to weigh down the wheel might simulate the suspension losses.

Suspension losses vary with speed (higher/lower vibration frequency), so TOUR‘s rocking rig probably would not work – it simply moves too slowly to replicate suspension losses at normal cycling speeds.

That brings us back to the steel drums. You’d have to make the drum huge to reduce the problems with the convex surface. The drum surface itself would have to be a true replica of actual pavement, not just a diamond tread. You’d probably want to map a bunch of road surfaces with a laser and then use EDM (electrical discharge machining) to engrave an ‘average’ road surface into the steel drum surface. You could make interchangeable plates covering the drum with several road surfaces that feature different roughnesses. And why not a gravel road, too?

Validation

To validate your test rig, you’d take a fast, a middling and a slow tire, and test them on the road, just like Bicycle Quarterly has done. If your drum test results match those on the real road, then you can be confident that they replicate real-world conditions.

Back to Real-Road Testing

As you can see, making a useful test rig is a huge undertaking, which is probably why nobody has done it yet. For now, tire companies continue to develop their tires with the help of simple steel drum tests. That may be the reason why they don’t offer their supple high-performance models in truly wide versions: The steel drum tests indicate that you lose performance quickly as you run tires at lower pressures. And since supple, wide tires cannot support high pressures, steel drum tests suggest that wider tires should strong and not supple.

At Bicycle Quarterly, we’ll continue to test tires on real roads. To get good results, we can’t just put a power meter on a bike and go for a ride, then change the tires and repeat. We must keep the conditions the same for all tests. First, this means testing in a controlled setting, like a track. Second, we must control the variables tightly: test only on days with no wind and constant temperature, test each tire multiple times, and do a rigorous statistical analysis of the results.

The statistics are important, because there always will be some ‘noise’ – even in a lab test, because the tire warms up the longer you run it on the machines. The statistical analysis shows where you are recording real differences between tires and where you just see ‘noise.’

After more than a decade of testing tires under real-world conditions, we can say with certainty:

- Supple casings, more than anything else, determine the performance of your tires.

- Wider tires roll as fast as narrow ones on smooth surfaces, and faster on rough ones.

- Higher tire pressures don’t make the bike faster.

There is little doubt about these findings any longer – they’ve become widely accepted, even though the lab tests still haven’t caught up to the new science. But for us as riders, what matters is how well our tires perform on real roads, not on a steel drum.

Further reading:

- Bicycle Quarterly‘s tire tests are available as a 4-Pack of Back Issues.

- Compass tires were developed using the results of Bicycle Quarterly‘s tire tests.