Too Much Tire? A Road Test.

“That’s too much tire for that route,” is something I’ve heard many times, usually from gravel racers who are preparing a relatively smooth ride, like next weekend’s SBT GRVL in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. The old belief that the narrowest tire that can (barely) handle the terrain will be fastest doesn’t seem to be going away, despite much data that shows wide tires rolling as fast as narrow ones.

I can understand that. There is data showing all kinds of things—even that higher tire pressures roll much faster. What really matters is how this plays out in the real world. In other words, any testing needs to be confirmed on the road.

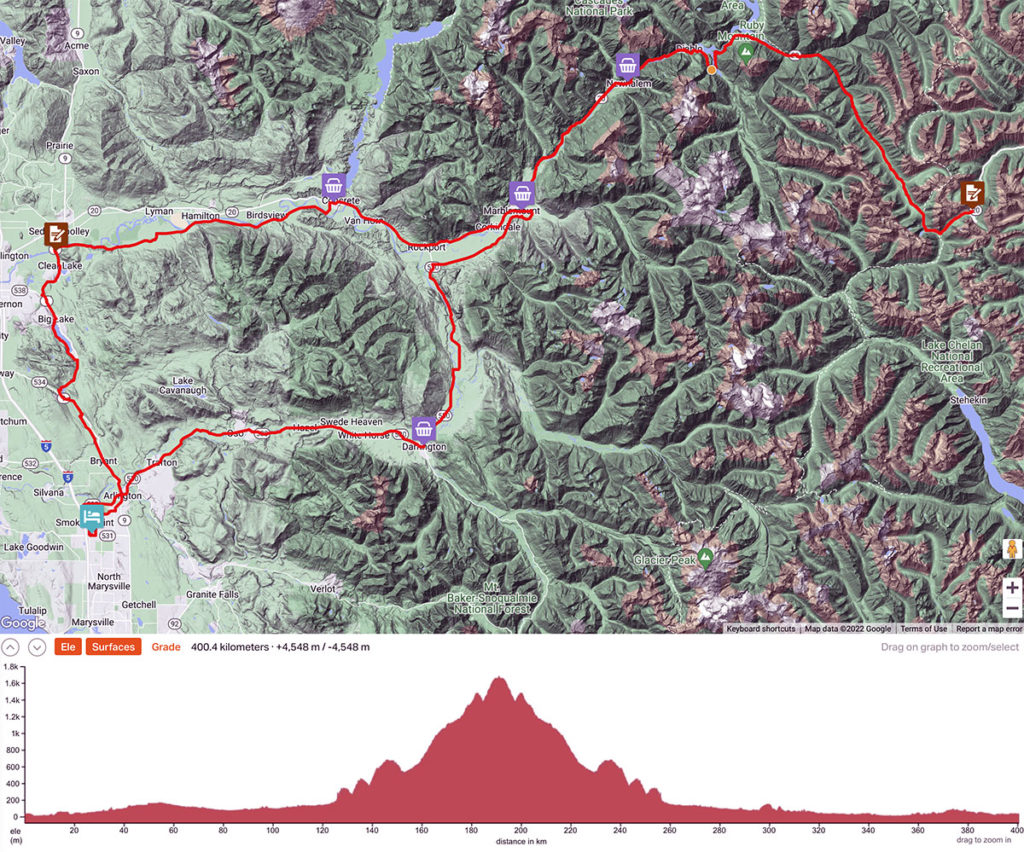

Last weekend’s Seattle International Randonneurs 400 km brevet was a great opportunity for this ‘road test.’ The course is on pavement all the way, with a mix of smooth and somewhat rough surfaces. The ride starts with a long stretches of (almost) flat road, where any penalty in rolling resistance would be noticeable. The monster 60-km climb up to Washington Pass (elevation: 5,476 ft) will show up the added weight of the bigger tires, if it makes a difference. On the descent, any added aerodynamic drag should be noticeable, especially since there’s usually a headwind. To top it off, the ride is 250 miles (400 km) long. Small effects will make a big difference at the end of such a long day.

And I already mentioned that the entire course is paved. In other words, if there is a course where ‘too much tire’ would be a disadvantage, it’s this one.

The Oregon Outback Rene Herse wasn’t designed for courses like this, but my 650B randonneur bike with its 42 mm tires has been used for testing prototype components, and it wasn’t ready for last weekend’s ride. After a moment’s hesitation, I decided to take the Oregon Outback bike with its 26″ x 2.3″ tires. The bike was still dusty from the 3 Volcano 300 km Brevet two weeks ago—it’s nice to have a bike where I just need to inflate the tires, and it’s ready for another big adventure.

This would be a good test of the idea that ‘there’s no such thing as too much tire.’ (Of course, there must be a point where tires become too wide, but our testing suggests that 54 mm isn’t that wide yet.) I inflated the tires to 1.8 bar (26 psi), the ‘soft’ value indicated by the Rene Herse Tire Pressure Calculator. If I was going to run wide, soft tires, I might as well go all the way!

Remarkably, I wasn’t the only one on Rat Trap Pass tires. David (?) was riding his beautiful Rodriguez custom. (Sorry for the blurry photo, shot with my cell phone as we lined up for the 5 a.m. start.) In fact, almost half the riders were on randonneur bikes with wide tires, handlebar bags, etc.

Tire testing was definitely not on my mind as our group headed toward the rising sun, with the Cascade Mountains looming on the horizon. This promised to be a gorgeous day.

As we rolled eastward on false flats, the mountains were getting closer. Fog was rising from pastures. The cool morning air seemed full of anticipation. The first rollers saw the pack split up, with Ryan and I opening the road. And what a road it was! The highway that took us deep into the heart of the Cascades saw little traffic as it curved through the valley.

Then we turned onto Rockport-Cascade Road. No more cars at all. Morning sunlight filtering through the trees. The road rising very gently with a few rollers to stretch our legs. A perfect start for a day on a bike.

When I rode here years ago on 32 mm tires, the surface was very rough. The road hasn’t been repaved, but it felt much smoother today. That’s 54 mm tires and 26 psi for you! Ryan didn’t complain, either. He was on 42 mm tires—certainly ‘enough tire’ for this road.

What about our speed? We covered the first 100 kilometers, slightly uphill, in just under 3:30 hours. That works out to an average of 28.6 km/h (17.8 mph). This includes a short stop to buy supplies for the long climb ahead. I know I wouldn’t have been any faster on narrower tires. After all, we still had 300 kilometers of climbing and winds ahead of us.

And then we were in the mountains. Ryan stopped at a rest stop to get some water, before continuing at his own pace. My big-tire bike climbed eagerly. The combination of superlight steel tubing (and associated frame flex) and wide tires makes the bike respond well to my pedal strokes. I was working hard, but I never felt inclined to say: “Shut up, legs!” (as German pro racer Jens Voigt famously titled his book.)

One other rider—on a racing bike—had almost caught up to us by this point. From time to time, I could see him behind. He was riding with a more constant power output, so he was a little slower on the steeper pitches and re-gained the lost ground on the shallower stretches.

Climbing long passes, fueling is the hardest part. Eat too little, and you bonk. Eat too much, and your stomach can’t digest the food and starts to reject it. The day was getting hot, which added to the challenge. I usually err on the side of too little food—it’s easier to recover from ‘hunger knock’ than from an upset stomach—but I didn’t want to run out of energy on the long uphill, either. Turns out I overdid the calories a bit.

Toward the first pass, my stomach started to feel queasy. Fortunately, the top was near, and I could slow down without losing much time. Just as I crested the pass, the other rider zipped by. If my wide tires made me climb significantly slower, he’d have passed me long before this point, 180 km (115 miles) into the ride.

A short, fast descent, then another steep climb, and we’re at the top. Washington Pass is one of the highest in the Cascades, at 1669 m (5,476 ft). Bill Dussler, the organizer, had set up a control here. Not only did he sign our cards, he also offered water and cold melon slices. That and his always-smiling personality provided the encouragement I needed to continue without much delay.

Then came the big descent. One nice thing about out-and-back courses is that all riders get to see each other. Everybody was riding strong on this day. We waved and shouted encouragements. (Photos were a bit more difficult while descending at high speed.)

Fourty miles (65 km) of descent may sound like a dream, but it’s actually hard work: Without the forces of pedaling pushing up my torso, there was much more weight on arms and hands. Short uphills punctuated the long downhill and helped a bit in that respect, but my shoulders were getting tired.

At least the headwinds didn’t bother us much today. I’ve seen them so strong that riding down the pass required pedaling hard just to keep going. The infamous sidewinds can almost blow you off the bike. There are even road signs on the highway warning of ‘severe sidewinds.’ It’s wasn’t much of a problem on this day. A few gusts did hit my bike, but the low-trail geometry helped: It gives the wind less leverage over the bike’s steering. The whole bike gets pushed sideways a bit, but it doesn’t change its course like a high-trail bike where the side wind turns the handlebars.

The (head) wind got stronger as I left the mountains. I’m relatively tall, but not very muscular, so my wind-resistance-to-power ratio is not very favorable. Headwinds can be very discouraging. Years of riding have attuned me to the wind intensity as the air rushes by my ears, yet today, the bike seemed to slip through the wind easier than usual. That’s the opposite of what I expected with the wide tires.

Then I remembered: For the winds of the Oregon Outback, I had installed relatively narrow 40 cm handlebars. That’s 2 cm less than I usually ride. This probably makes a bigger difference than the 1.2 cm wider tires compared to those on my 650B bike.

That got me thinking: Few riders talk about their handlebar width in terms of performance. And yet our wind tunnel tests have shown that reducing the rider’s frontal area has big benefits: When we lowered the bars by 2 cm, wind resistance was reduced by 5%.

Lowering your handlebars by 2 cm can affect comfort and power output, but 2 cm narrower bars are barely noticeable. In fact, my bike didn’t feel any different from my other bikes with wider bars. Our elbows articulate, and whether our forearms point a little more inward or not doesn’t affect our shoulders, chest, breathing, etc. (This is if you ride with your elbows bent. For cyclists riding with straight arms and locked elbows, wider bars will be more comfortable.)

The effect is significant: 5% less wind resistance is twice the effect of a set of aero wheels. Speaking of aero, it also seems like the aero ‘fenders’ make a difference—not only in the wind tunnel, but also on the road.

We passed through Concrete, a town that got its name from the cement factory that used to be here. That’s why the town has many concrete buildings, including this huge grain elevator that now serves as a landmark. For us, it meant turning off the highway, cross the Skagit River, and continue on a little-used backroad.

The South Skagit Valley Highway is a highway in name only. The two-lane road undulates as it climbs the bluffs above the river, then drops back to water level. Tree crowns touch above the narrow blacktop, creating a beautiful komorebi pattern of light-and-shade in the evening sun. On this day, the trees had the added benefit of blocking the wind. With almost 200 miles (320 km) on the odometer, my legs would have been tired if the wide tires had been slowing me down. Instead, the beautiful road gave me a burst of energy. Strava shows that my speed actually went up from this point.

I was approaching the finish when the sun set. I lost a little time when my GPS suddenly went dead because the battery was empty. (Note: Even on the most energy-efficient settings, the Wahoo Elemnt Bolt has a run time of just over 16 hours.) With less than five miles to go, I had to stop and dig through the accumulated detritus of the all-day ride to find power pack, cable and helmet light. Rather than re-start the Wahoo’s navigation, I rode to the finish using my hand-drawn cue sheet. At 9:30 p.m., after 16:30 hours on the road, I rolled to a stop at the hotel in Arlington. The rider who had passed me more than 200 km ago had finished 25 minutes earlier. Mick Walsh, part of the organizing team, was on hand with pizza, cold drinks and a cheerful smile.

Knowing my form this year and the course, I’m very happy with my time. The wide tires didn’t slow me down in any noticeable way. In fact, the ride went better than I expected. Perhaps those narrow handlebars helped on this windy day… Rather than worry about ‘too much tire’ for an event, maybe we should think about ‘too much handlebar’!

A few afterthoughts:

- Will I ride all brevets on 54 mm tires from now on? Unlikely. While the cantis on the Oregon Outback bike work really well now that the pads are completely bedded, I do prefer centerpull brakes. Their linear, powerful and smooth braking is on another level—something I appreciate on twisty descents with tight hairpins where I like to brake deep into the turns. Why not make centerpulls for 54 mm tires (and fenders)? Making brake arms that large would add a lot of weight—and look clumsy. If I was running discs, my decision would be less clear-cut. In that case, I might run Rat Trap Pass tires all the time.

- This also points to the reason why some riders will prefer narrower tires and/or higher pressures: They may not roll faster, but they change the feel of the bike. Depending on your pedal stroke (and your frame’s flex characteristics), a harder tire may feel better and allow you to put out more power.

- Tire pressure: At 1.8 bar (26 psi), the wide tires felt a little bouncy at first. This didn’t slow me down, but if I were to sprint for city limit signs, I’d run the ‘firm’ pressure recommended by the Rene Herse Tire Pressure Calculator: 2.2 bar (32 psi). The bike would be just as fast, but it would feel more like a road bike.

- This road test alone doesn’t prove anything—it’s just anecdotal evidence. However, it confirms what we’ve found in carefully controlled tests. That said, it is possible that wider tires a very slightly slower (or faster). If that is the case, then the difference is too small to be noticeable on the road. Other factors (like handlebar width) are more important.

- Had the course included any rough stretches, the wide tires would have been faster. Even a few miles of gravel are enough to make a large difference, as I found out during the 3 Volcano 300 km Brevet two weeks ago.

- Strava says that I stopped 45 minutes during the 16 hours on the bike, but that includes every stop sign (of which there were only very few), photo stop, pee break, etc. ‘Real’ stops were just three: At km 100 to buy some supplies, at km 190 (top of the pass), and at km 280 (buy supplies, eat ice cream, drink). It’s still amazing to me how comfortable these bikes are: We can ride all day without needing (or even wanting) to stop.

- After two brevets in a short time, I’m looking forward to more leisurely rides. Maybe attach the low-rider racks to the bike, pack two panniers, and head to the mountains for a short camping trip?

Further Reading:

- Our book The All-Road Bike Revolution goes into detail of aerodynamics, rolling resistance and everything else that makes a bike fast, comfortable and reliable.

- This ride on Strava.

- Measurements of tire performance for different widths under carefully controlled conditions.