Tour de France Cyclotouriste

This year’s Tour de France provided gripping racing and a worthy winner: Tadej Pogačar rode a smart, powerful race, and his second win in a row promises more for the future. Especially since he’s just 22 years old and at the beginning of his career.

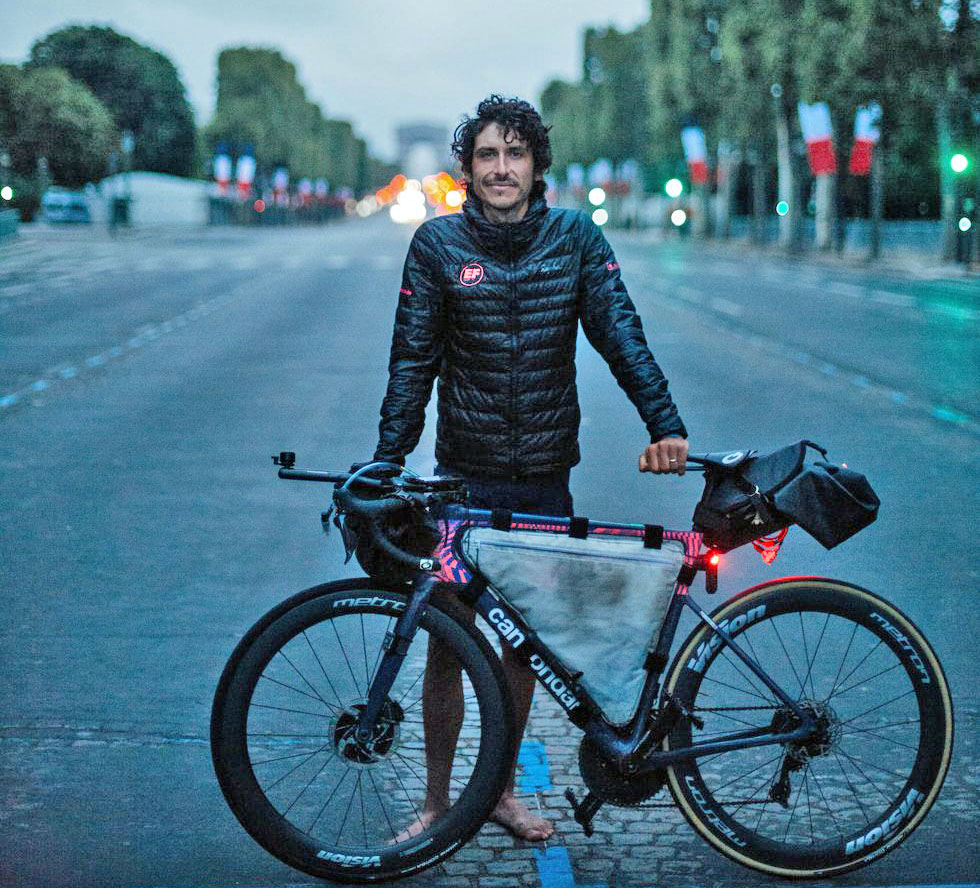

And yet one of the most recognized feats of this year’s Tour wasn’t part of the official race at all: Lachlan Morton’s ‘Alt Tour’ consisted of covering the entire course of the big race, plus the transfer stages – riding unsupported. His goal was to beat the race to the finish on the Champs Elysées in Paris, and he made it by five days.

Lachlan’s challenge was in the best tradition of randonneuring: Setting a long-distance goal that is achievable, but requires giving it all you have. And he did – camping by the roadside and even riding through knee trouble that had him finish the big ride in sandals.

Lachlan has written that his ride was inspired by the early years of the Tour de France, when stages were long and full of adventure. Back then, amateurs were allowed to enter as touriste-routiers – with the idea that they wouldn’t get in the way of the big racers.

Riding as a touriste-routier was similar to the challenge Lachlan set for himself: There was no support, and racers had work on their own bikes and figure out their own logistics. During the 1920s, one rider earned money after each stage by performing acrobatic tricks, so he could pay for his hotel that night!

The touriste-routiers were a colorful crowd. One of them, Joanny Panel, was the maker of the first commercially available derailleur. To prove the worth of his ‘Le Chémineau’ (The Wanderer), Panel entered the Tour in 1912, 1913 and 1914. In 1913, Panel rode so well that Tour organiser Henri Desgrange suddenly changed the rules. Apparently he was afraid that this amateur on a cyclotouring bike would upstage his pros. Desgranges solution was simple: Require all riders to complete the next stage on fixed gears! Robbed of his advantage and not trained to ride a fixed-gear over the hilly terrain, Panel lost much time.

In 1931, another touriste-routier charged into the limelight. The touriste-routiers started ten minutes behind the pros, but Max Bulla was strong enough to overcome that handicap and win the first stage and the yellow jersey. Like Bulla, many touriste-routiers were strong racers who hadn’t found a spot on one of the National teams that raced the Tour back then. In Bulla’s case, Austria was too small a country to field a Tour team, so he rode as a touriste-routier. His accomplishment was lauded by the Tour organizers and the press, but he still had to start the next stage with the ten-minute handicap. This time, the pros made sure he didn’t catch them, and Bulla lost the yellow jersey. To this day, he is the only Austrian who’s ever worn the maillot jaune.

When the Tour de France became a big media event, there was no room for touriste-routiers any longer. But that didn’t stop the fascination the race held on strong riders who wanted to try their mettle – like Lachlan did this year.

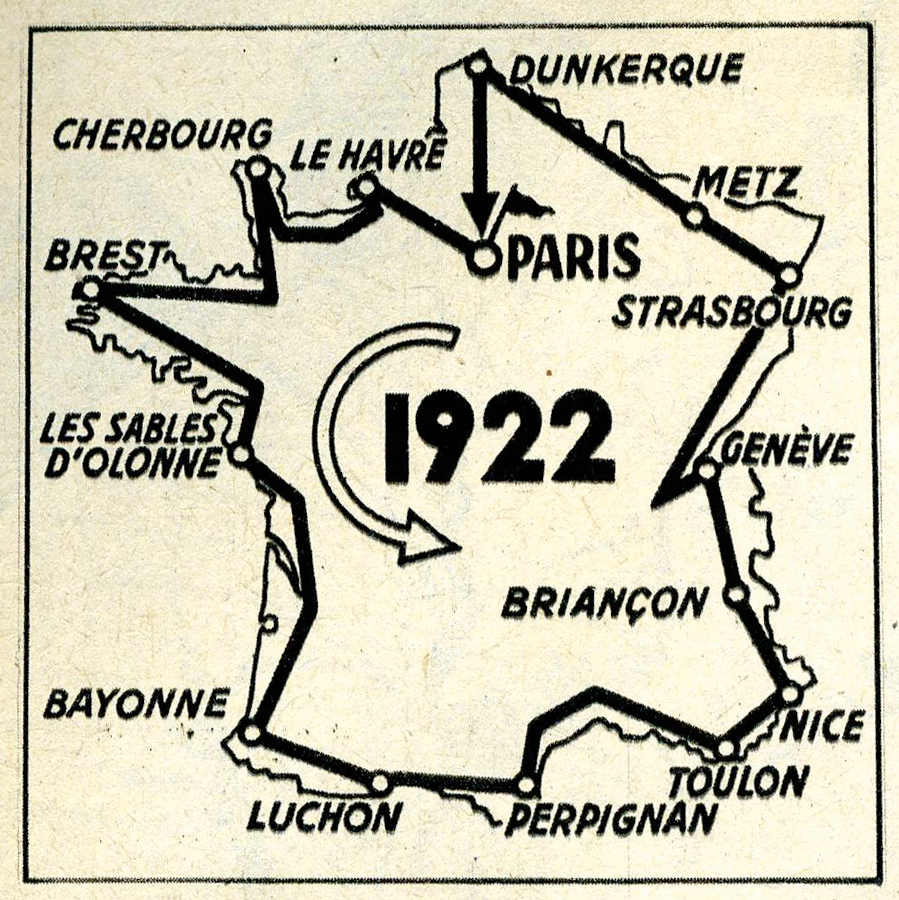

Enter the Tour de France Randonneur et Cyclotouristique. This event has been organized since 1959 by the Union Sportive Métro (the sports club of the public transit authority of Paris). It takes riders around the perimeter of France on the tranditional course of the Tour (above) – before commercial priorities led to today’s convoluted course with multiple transfer stages.

You can ride the Tour Cyclo whenever you want, from June to September (provided the high mountain passes along the course are open). Riders visit 60 towns and checkpoints along the way and either get their cards stamped or send postcards as proof of completing the course. In between, riders choose their route as they want. (The U.S. Métro provides recommendations.)

The course covers roughly 4,800 km (3,000 miles), and there are two versions: The Tour de France Randonneur allows 30 days to complete the big loop, while the Tour Cyclotouristique gives riders 60 days.

Some have done it much quicker: In 1978, Patrick Plaine rode the entire Tour in just 13 days 9 hours! That’s four days faster than Lachlan. (However, the Tour Cyclo’s is about 700 km (450 miles) shorter than Lachlan’s course.) Patrick Plaine didn’t have a media team, and there are few photos of him during his rides. The image above shows him in 1998, during his 17th Tour Cyclo!

In case you wonder how an amateur like Patrick could be faster than a professional racer, it’s like the classic story of The Tortoise and the Hare: As a randonneur, Patrick was comfortable riding at night. So he stopped far less. And we shouldn’t forget, Lachlan’s goal was to beat the pro peloton, and not to go as fast as possible…

What makes the Tour Cyclo achievable for mere mortals is that you can do it in two or three stages. You are allowed up to one year between the stages. So you could ride one half of the Tour in two weeks during one year and the rest the following year.

Raymond Henry did just that. The great historian of the French cyclotouring movement and Bicycle Quarterly contributor completed the Tour de France Randonneur over two summers during the early 2000s, riding his 1952 Jo Routens bike (above). He called it one of his most challenging and beautiful rides.

Our friend Victor Decouard also completed the Tour de France Randonneur over two summers. His partner Sina Witte joined him the second year (above). What a team!

It’s exciting that Lachlan’s big ride shines a spotlight on the rich tradition of randonneuring. This sport has always been about challenging rides that are limited only by our imagination. Whether we ride in an organized event like the Tour de France Cyclo or create our own challenges, it’s a rewarding way of expanding our cycling horizons.

Further reading:

• Official web page of the U.S. Métro for the Tour de France Cyclotouristique and Randonneur