Trail Does NOT Make a Bike Stable

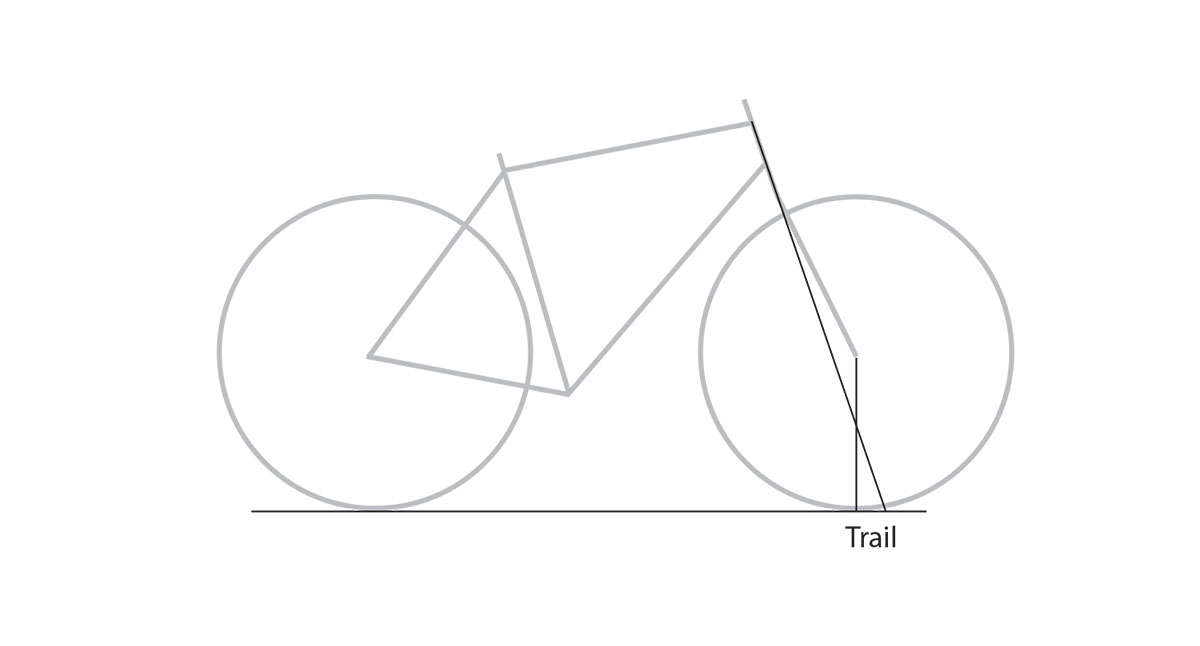

For decades, cyclists have believed that trail makes a bike more stable. It makes sense: A bike’s front wheel touches the ground behind the steerer axis. As the bike moves forward, there’s a self-centering force on the front wheel – sort of like the caster of a shopping cart.

Trail is the distance between the steerer axis and where the wheel touches the ground. Trail is determined by the bike’s head angle, fork offset and wheel size.

At first sight, it seems to make sense that more trail means more self-centering force. That’s why we (and pretty much everybody else) used to believe:

More trail = More stable

Then we rode many different bikes and noticed something…

In the video, I am riding down a challenging trail section. There’s a very sharp left turn as the trail goes around a fallen tree. To make that low-speed turn, I need to turn the fork almost 45 degrees while the bike doesn’t move forward a lot. In the first part of the video, I ride a low-trail bike. In the past, most experts would have considered that bike to be ‘borderline unstable.’ In the second part, I ride a high-trail bike. Most people would think the second bike was more stable. Both bikes have the same wheels and tires, so we can focus on the effect of trail.

As it turns out, I was unable to make the tight turn on the ‘unstable’ low-trail bike. And yet I could turn without problems on the ‘stable’ high-trail bike. In this situation, the ‘stable’ bike was more agile.

We repeated the descent many times. The result was always the same: The high-trail bike turned without problems. The low-trail bike didn’t make it around the sharp corner. It’s not that this particular low-trail bike was somehow flawed – we took my low-trail Firefly (above) to the same corner, and the result was the same. So it wasn’t the handlebar bag on the first low-trail bike, either: The Firefly, without a bag, didn’t turn any better.

Familiarity?

“What works best is what you are used to!” is what you often hear. Not in this case: I’ve ridden my Firefly many thousands of miles. My experience on high-trail bikes is more limited. And yet the high-trail bike was easy to turn. My own bike was not.

It also wasn’t for a lack of trying to make the low-trail bikes turn. I love my bike – and I wish I could tell you it’s the best in all conditions. (There are many other situations where the low-trail geometry does work better for me.)

Lower BB?

What about bottom bracket height? Many riders believe that a lower bottom bracket (and lower center of gravity) will make a bike turn better. Not in this case: The two low-trail bikes have lower bottom brackets than the high-trail bike. Yet the high-trail/high-BB bike was more agile in this situation.

Wheel Flop!

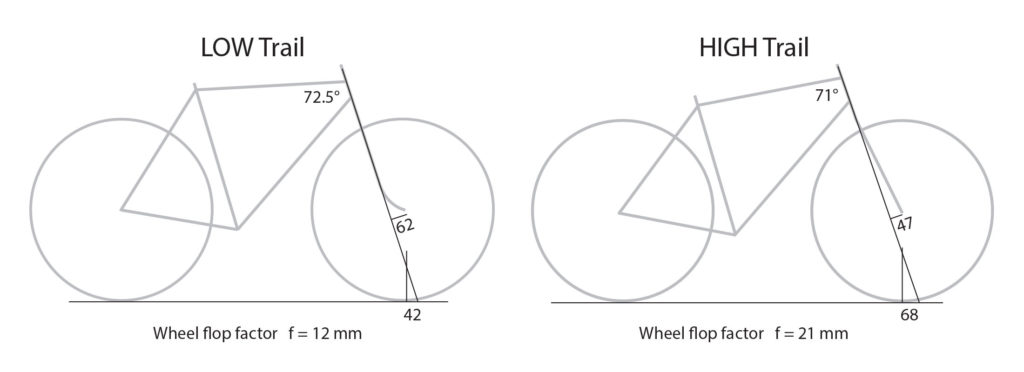

What is going on here? What determines the maneuverability during these low-speed turns is wheel flop, not trail. Wheel flop is an odd side-effect of the complicated things going on at the front of the bike. For example, the front wheel moves sideways when you turn the fork because it’s ahead of the steering axis. The result is that as you turn the handlebars, the front of the bike is lowered. That’s right – if you turn the fork, the front of the bike goes down. And that works the other way around, too: If you push hard on the front of the bike while the fork is turned a bit, the fork will turn further. This works like power steering in a car – it reinforces any movement of the handlebars. The more wheel flop a bike has, the more power steering it has.

(There is some confusion about what wheel flop is: Some people believe it’s when the fork turns while the bike is stopped, because the weight of the handlebars rotates around the inclined steerer axis. That’s a different factor that doesn’t have a catchy name yet.)

So wheel flop is like power steering – it helps turn the fork. And wheel flop is proportional to trail. The low-trail bike has little wheel flop – there isn’t much ‘power steering.’ The high-trail bike has more wheel flop/power steering so it’s easier to turn the handlebars quickly. And that’s why the high-trail bike is easier to steer around tight corners: It has more wheel flop, more ‘power steering.’

Bike Geometry is Complex

Bike geometry is not as simple as one geometry being ‘more stable’ than another. Different geometries work for different purposes. The high-trail/high-flop bike is great on tight singletrack, as we saw in the video. That’s why mountain bikes have a lot of trail.

And I still prefer low-trail bikes!

We just showed that the high-trail bike handles tight singletrack better, and yet I’m not going to get rid of my low-trail bikes. Why? Because I mostly ride on roads – paved or gravel – where speeds are higher.

The low-trail/low-flop bike works better in high-speed corners, where you set up the bike and don’t turn the handlebars much at all. On steep climbs, the low-trail bike is easier to ride on a straight line. (There is less wheel flop that’ll exaggerate the handlebar movements inherent in balancing the bike.) The low-trail bike is also better suited to a handlebar bag or front panniers.

There’s a lot going on with bike geometry. There’s a reason why mountain bikes are so different from all-road bikes. There’s less agreement on what makes a great gravel bike, because the industry hasn’t figured out what a ‘gravel’ bike really is: a drop-bar mountain bike or a road bike with wide tires. If you’re in the market for a gravel bike, understanding these differences is essential, so you buy a bike that is optimized for the riding you do.

Bike geometry is just one of many topics discussed in detail in our book The All-Road Bike Revolution. If you are curious about how bikes really work – beyond old simplifications like ‘More Trail = More Stable’ – you’ll find answers in the book. All our research starts with riding bikes, so we don’t talk about some dry theory, but things that you can observe on the road – things that are applicable to real-world riding. Click here to order your copy in English or German.

Videographers: Steve Frey, Mark Vande Kamp