Tune Your Tires!

With wide tires, you can tune the ride of your bike to the terrain and to your personal preferences. This gives you options that simply did not exist in the past.

Gone are the days when we inflated our narrow tires to the maximum pressure and rode on rock-hard rubber. Even with narrow tires, you can lower the pressure a bit to get a (slightly) more comfortable ride. Of course, there is only so much you can do – the feel of the bike won’t really change. There is simply too little air, and you’ll get pinch flats if you reduce the pressure enough to make a real difference. The only way to transform the feel of a racing bike is to get different tires – that’s why professional racers have always run hand-made tubulars with supple casings (well, at least since the 1930s).

With wide tires, supple casings also make a huge difference. In addition, you can choose your tire pressure over a wide range: The 54 mm-wide Rene Herse Rat Trap Pass tires that Hahn is running in the photo above work great at pressures between 20 and 55 psi. That means you can cut the pressure to almost a third of the maximum, if you want. (For comparison, this is like running narrow 120 psi racing tires at 45 psi. Don’t try this with 25 mm tires!)

With wide tires, you can tune the feel of your bike by adjusting the tire pressure. The same tire will feel completely different depending on how hard you inflate it. This is something that you really start to notice with tires that are wider than 40 mm.

At 55 psi, my Firefly with its Rat Trap Pass tires feels firm and buzzy like a road bike on narrow tires. There is no noticeable flex in the tires, no matter how hard you corner, or how fast you sprint. You’ll feel every detail of the road surface almost unfiltered. The extra air does take off some of the harshness, and the extra rubber gives you more grip, but the feel is similar to a bike with narrow, high-pressure tires.

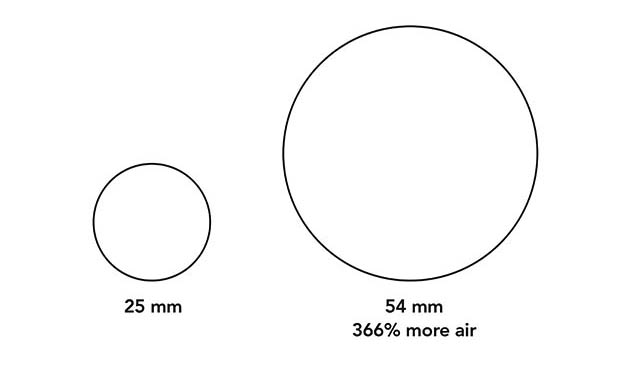

Why doesn’t the 54 mm Rat Trap Pass feel wallowy like a 25 mm tire at 55 psi? If you think of the tire as an air spring – a piston in a cylinder – then pressure is only one factor. The other is the diameter of the air cylinder. To compress a 54 mm tire takes more force than to compress a 25 mm tire, even if both are inflated to the same pressure.

Even with wide tires, you can get the feel of narrow tires, if you inflate them to (relatively) high pressure. But you also have options to tune your bike by letting out some air.

At first, not much is happening – 55 psi is far more than most riders will ever want to use in these tires. At 30 psi, you still get the firm feel of a ‘road bike,’ but more shock absorption and even better traction. This is the pressure I ride on very smooth roads.

At 25 psi, the tire has a lot more compliance. Now it really feels like an ultra-wide tire. It still corners great, but you can go over bumpy roads and really feel the suspension. This is the pressure I use on most paved roads.

On rough gravel, I let out even more air. At 20 psi, the tire really floats over the gravel. This is how I imagine a rally car with ultra-expensive shock absorbers feels: ‘breathing with the surface,’ gently going up and down over bigger undulations, but insulating you from the smaller bumps and vibrations. It’s an amazing feeling, and, without the bike bucking under you, you can put down power at all times. It’s fun to ride at ‘road’ speeds on rough gravel.

And even at this low pressure, there is enough air to prevent the tires from bottoming out. Even with tubes, I don’t get pinch flats – unless the terrain is really rough and rocky and speeds are ultra-fast.

When you’re descending at very high speeds on very rough terrain, you’ll have to increase the tire pressure a bit to avoid bottoming out too often. Even if you run your tires tubeless, you risk cutting your tires and damaging your rims if you bottom out too often and too hard.

When you return to pavement, 20 psi isn’t enough. The tire starts to squirm and run wide in corners. When you rise out of the saddle, it feels wallowy as it compresses under the thrust of your pedal strokes. And if you really push the limit, the tire can collapse in mid-corner.

Back on pavement, I inflate the tires back to 25-30 psi. If my ride includes both pavement and gravel sectors in quick succession, I often just keep the pressure around 25 psi, so I don’t have to mess with it.

Tire pressure is not just about shock absorption – it also affects the power transfer of your bike. A frame that is too stiff for the rider’s power output and pedaling style is harder to pedal – a little compliance smoothes out the power strokes and allows the rider to put out more power. We call this ‘planing,’ but it’s hardly a revolutionary idea.

Usually, that compliance comes from the frame. That is why high-end, superlight bikes perform so well, even on flat roads where the weight doesn’t matter. The lighter frames use less material, which makes them more flexible. Conversely, ultra-stiff bikes can feel ‘dead’ and hard to pedal to many riders.

With wide tires, that compliance can come from the tires, too. When we tested the Jones (above), we found it to perform wonderfully with its tires at ‘gravel pressure.’ When we aired up the tires for a fast road ride, the bike suddenly felt sluggish. This is the opposite of what conventional wisdom might tell you, but when we lowered the tire pressure again, the wonderful performance of the Jones was back. This has nothing to do with rolling resistance – it’s all about how much power we could put out thanks to the added compliance in the system. The Jones ‘planed’ best with its tires at relatively low pressure. This means that you can use tire pressure to adjust how much ‘give’ you have in your bike’s power transmission. I’ve found this a useful tool to get the most out of many Bicycle Quarterly test bikes.

Speaking of rolling resistance – don’t tires roll slower when you let out air? At least with supple tires, tire pressure makes no discernible difference, not even on smooth roads. As long as you have enough pressure that the bike is rideable, your tires roll as fast as they do at higher pressures. And on rough roads, lower pressures will be faster, both because the suspension losses are reduced and because you can put out more power.

Tuning your tires is fun. It optimizes your bike for your preferences and for the terrain you ride. Of course, tire pressure first and foremost depends on your weight – the numbers in this post assume a bike-and-rider weight of about 80 kg (175 lb).

Tire pressure also depends greatly on the casing of your tires. The values in this post are for Rene Herse Extralight tires. With Standard or Endurance casings, you can run about 10% less pressure. With a stiffer casing, you run even less air, all the way to airless tires that run at zero pressure. As your tires get stiffer, you lose the ability to tune your ride, because air pressure plays a smaller role in supporting the bike-and-rider’s weight. The beauty of supple tires is that air pressure is the main component that holds up the weight of bike and rider. This makes it easy to tune your tires.

Rather than inflate your tires to a set number, experiment with tire pressures to see how this changes the feel of your bike. Also remember that the gauges on pumps aren’t always accurate – use them only to replicate a setting that you’ve found useful in the past, rather than try to inflate your tires to an exact pressure. Once you’ve found values that work, you can quickly change the feel of your bike based on where you’ll ride and how you want your bike to feel. This makes cycling even more fun!

Further information: