Why we call it a Revolution

The word ‘Revolution’ is overused. Almost every new product and idea is marketed as ‘revolutionary.’ And yet, once in a while, something happens that really does change everything. For bicycles, the ‘All-Road Bike Revolution’ has been perhaps the biggest change since multi-speed drivetrains replaced singlespeeds. The ‘All-Road Bike Revolution’ can be summed up in one line:

Comfort = Speed

For many decades, we believed that comfort and speed were diametrically opposed. Cyclists were told that they had to choose: If you wanted more comfort, you gave up speed. If you wanted speed, you had to suffer. The cycling world was split into fast, but uncomfortable, race bikes and slow, but comfortable, touring bikes. And then there were mountain bikes that could go off-road, but also had to sacrifice speed for that go-anywhere ability.

This also meant that if you enjoyed going fast, you stuck to smooth roads, because that’s all your race bike could handle. If you liked exploring off the beaten path, you gave up not just speed, but also the effortless feel of a performance bike. That was probably the main reason why many of us kept returning to racing bikes: Speed isn’t a just goal in itself, but a bike that performs well is more fun, too!

All that has changed. Today, one of my fastest bikes runs 54 mm tires, which I pump up to ridiculously low pressures. And yet it’s no slower than the fastest race bikes we’ve tested. In the past, a ride like the Oregon Outback, which is 75% rough gravel and 25% smooth pavement, required compromises when choosing your bike: You’d choose the narrowest, hardest tires that still worked OK on the gravel, because you didn’t want to give up too much speed on the paved sections. Now I just run on the widest tires I can fit on a performance bike. I don’t even bother to change the tire pressure when transitioning from rough gravel to smooth pavement, knowing that there’s no real difference in speed whether I run my big tires at 19 psi or 55 psi (1.3 or 3.8 bar). The days when I routinely pumped up my tires to triple-digit pressures are long over!

Like so many big discoveries, the realization that comfort and speed are not opposed, but directly related, came about by accident. The reason why this was not discovered earlier was simple: Racers only wanted to optimize speed and didn’t worry much about comfort, because suffering for a few hours was worth it, if you won the race at the end. Cyclotourists weren’t in a rush, so they didn’t mind giving up speed for comfort.

As long-distance riders, we didn’t fit into either mold. Over a 1200 km ride like Paris-Brest-Paris (above), suffering will slow you down simply because it’s more fatiguing. So the racing mentality didn’t work. And yet we are trying for a personal best (or at least beat the time limit), so we didn’t want to give up more speed than necessary – which meant that touring bikes were a poor choice, too. Our research set out to find the best compromise between comfort and speed. We were curious if we could give up 5% in speed to gain 20% in comfort. For long-distance rides, that would be a good trade-off.

We tested tires with different widths and pressures to see how much speed we’d give up in exchange for more comfort. The results surprised us: Supple high-performance tires roll just as fast at lower pressures. You don’t gain anything if you inflate your tires rock-hard. We were searching for the best compromise, but we found that we don’t have to compromise at all: We can have superior comfort without giving up any speed!

This was so incredible – so revolutionary – that we tested again and again, with different methodologies, until we were absolutely certain: Inflating tires harder doesn’t make them faster. So what’s going on? The revolution is simply the realization that vibrations aren’t just uncomfortable, they also dissipate energy. These ‘suspension losses’ occur mostly in the rider’s body, where muscle and other tissues rub against each other. We feel that as discomfort, but it’s really friction between our body tissues. And friction costs energy, which has to come from somewhere. That energy isn’t available to drive the bike forward. In other words:

More vibration = less speed

Racers on their rock-hard 23 mm tires lost more speed due to these vibrations than they gained from the reduced flex and (possibly) better aerodynamics of their skinny tires. That’s why racers pretty quickly adopted our research and moved to 25 and even 28 mm tires. (Our tests showed that above 25 mm, wider tires are neither faster nor slower than 25s, at least on smooth roads.)

With wider tires, there is more flex (and friction) in the tires, but less vibration (and friction) in the rider’s body. The two effects cancel each other out for tires 25 mm and wider – you can choose whether you want to dissipate the vibrations in your tires or in your body. One is more comfortable than the other; both result in the same speed. That’s a truly revolutionary realization.

This revolution could only happen because we looked at the entire system of rider and bike. As long as tires were tested in the lab, without a rider, the suspension losses weren’t measured, and skinny, hard tires rolled faster. Those lab tests looked only at one part of the equation.

Testing tires in the lab is like testing bikes only on downhills. A heavier bike will be faster on a downhill. But we all know: The heavier bike will be slower on uphills. So much slower, in fact, that you will be slower overall on the heavier bike. Nobody tests bikes only on downhills, yet many ‘experts’ continue to test tire performance without a rider on the bike.

The Wide Tire Revolution

Like all revolutions, the realization that ‘Comfort = Speed’ had far-reaching consequences. It led to a revolution in tire design. In the old days, we thought that to make a tire fast, you needed a supple casing and high pressure. With narrow tires, that is no problem. But it doesn’t work with wide tires. Why not?

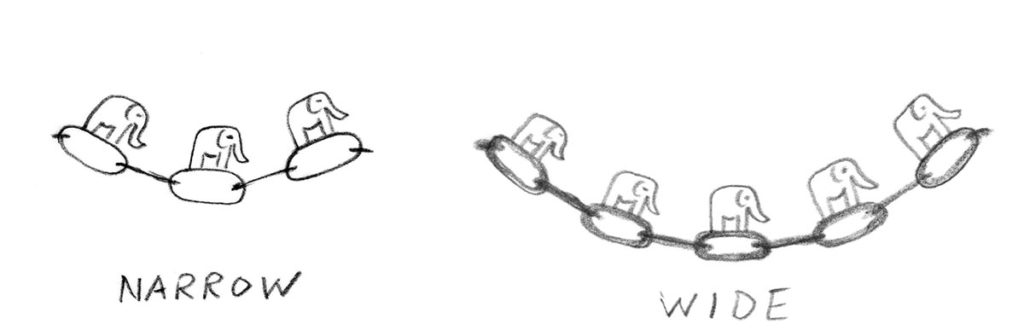

Imagine the tire casing as a chain (above). Tire pressure acts on each link. At high pressure, let’s assume there is the weight of an elephant on each link. With the narrow tire on the left, the ends of the chain must support the weight of three elephants. A supple casing – shown here as a thin chain – can handle that. With the wide tire, the weight of five elephants pulls on the ends of the chain. That means the chain needs to be 66% stronger. Back to tires, a wider tires needs a stronger casing if it’s going to have the same pressure rating. That means the wider tire will stiffer and slower.

Conventional thinking was that high pressures were essential for speed. And that meant you had to choose: supple casings or wide tires. You couldn’t have both. And since high pressure was considered more important than a supple casing, wide tires were stiff and slow.

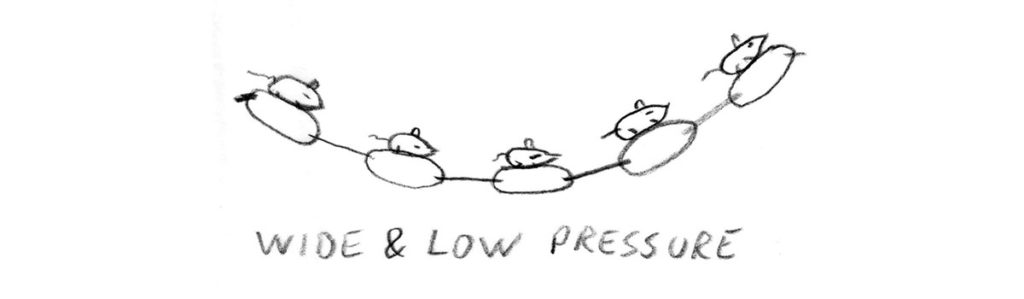

Once we found out that high pressures don’t make tires faster, the solution was obvious: Use supple casings and run the tires at lower pressures. Lower pressure means less load on the casing – basically, a mouse on each link of the chain instead of an elephant. It means that supple casings can be used for very wide tires. (A thin chain can’t support five elephants, but it’s strong enough for five mice.)

Real-world testing has confirmed the theory: Wide, supple, low-pressure tires are just as fast as narrow tires, even on smooth roads. (Since there are more vibrations on rough surfaces, wide tires are definitely faster on gravel, cobblestones, etc.)

This is the essence of the revolution: Wide tires and high performance were mutually exclusive as long as tires were designed for high pressures. Realizing that high pressures don’t provide any benefit, we can now design wide tires that roll super-fast – at low, comfortable pressures. When we first published these findings 15 years ago, no tire maker was willing to make the tires that, according to our research, had the potential to revolutionize cycling. So we started making our own tires…

There are other benefits of the ‘Tire Pressure Revolution’:

- Lower pressures mean fewer flats – a soft tire just rolls over debris that would cut a harder, narrower tire. This means we can ride supple wide tires in places where narrow racing rubber would suffer too many flats. It means we can enjoy the wonderful feel of a performance bike more often.

- Wide tires stabilize the bike through pneumatic trail. This means that we no longer have to choose between ‘twitchy’ and ‘stable’ handling. With wide tires, you can make bikes that are agile in corners and stable on the straights. That’s a topic for another day…

- Wide tires have more grip. They don’t just put more rubber on the road, but the lower pressure means the tires don’t skip and lose traction over bumps.

All-Road Bike Revolution

All this has led to a new type of bike: All-Road bikes combine the speed of racing bikes with the comfort and go-anywhere abilities of wide tires. In the past, you’d want a racing bike for going fast, a touring bike rolling along comfortably, and a mountain bike for riding on gravel. Now one bike can do it all.

You can even take the all-road bike on a camping trip, loading it up with front panniers or bikepacking bags. While the extra weight of the camping gear inevitably blunts the performance a bit, the bike retains the spirited feel of a performance bike. And that makes touring much more fun. Being able to use the same bike for so many things has opened up many new possibilities – like riding the Oregon Outback without having to compromise between comfort on gravel and speed on pavement.

Looking at the photo above, I’ve got to admit: Even to me, my Oregon Outback bike with full panniers doesn’t look like a super-fast bike. I have to ride it to remind myself how fast this bike (and others like it) really are.

We’ve tested this in our back-to-back and side-by-side comparisons, where we use two (almost) identical riders and switch bikes multiple times. Time and again, we’ve found that wider tires don’t make a bike slower. The All-Road Bike Revolution isn’t just some theoretical idea – it really works in the real world.

At this point, somebody will object: “If 54 mm tires are as fast as 25s, why don’t the pros in the Tour de France ride on ultra-wide tires?” The reason is simple: On smooth roads, wide tires are neither faster nor slower than narrow tires, but wider tires are a little heavier. If you are in a race that might be decided by mere centimeters in the final sprint, you want the lightest tires possible. For the rest of us, a few centimeters at the end of an all-out sprint don’t really matter…

The importance to get it right

Revolutionary all-road bikes can take many shapes – from carbon racers (above) to steel bikes like my Oregon Outback Rene Herse. But not every bike with wide tires performs well. Many wide ‘gravel’ tires are still made with sturdy – meaning: slow – casings, simply because they are cheaper to manufacture and easier to sell. And many ‘gravel’ bikes have stiffer, heavier and less performing frames than their road racing counterparts. That reinforces the belief that road bikes are faster, even though it’s an apples-to-oranges comparison. If gravel bikes are slower, it’s usually because they have slower tires, not because wider tires are inherently slower.

Unlike racing bikes, gravel bikes come in many shapes and forms, and they cater to many different riding styles. That’s a good thing, but it also means that it’s more important than ever to understand how these bikes work, so you can find one that’s right for you. That’s why we wrote our book ‘The All-Road Bike Revolution.’

You don’t need to read the book to agree that the all-road bike is truly revolutionary – a bike that combines race bike speed with the comfort and go-anywhere ability of wide tires. Realizing that this is possible has changed everything – even road bikes. They now run 28 or 32 mm tires, yet they are just as fast and fun as their narrow-tired ancestors. Because in this revolution, there are no losers, only winners.

Further Reading:

- The All-Road Bike Revolution – How to make your bike fast, Comfortable and reliable, available in English and German.

- Our tire pressure calculator helps you find the tire pressure where your tires roll fastest.

Photo credits: Rugile Kaladyte (Photo 2); Nicolas Joly (Photo 3)